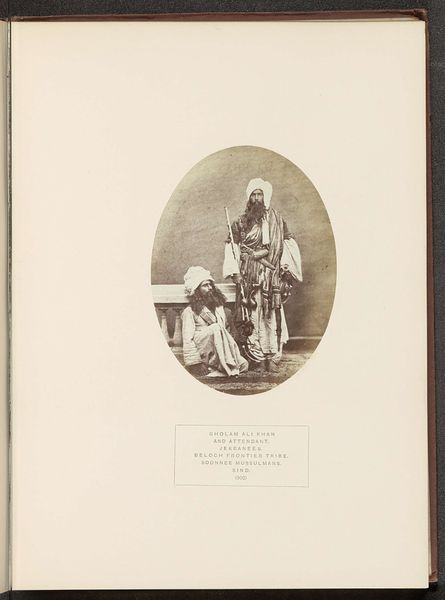

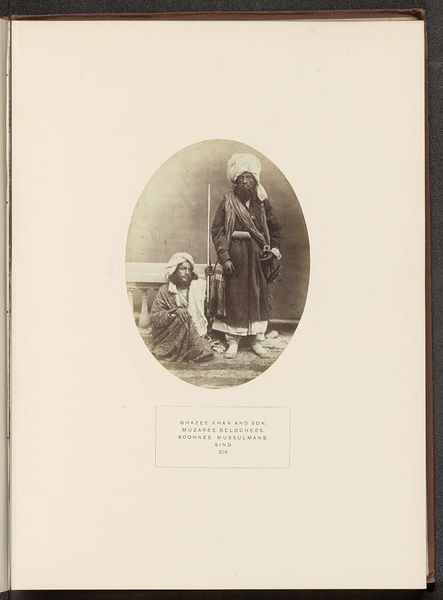

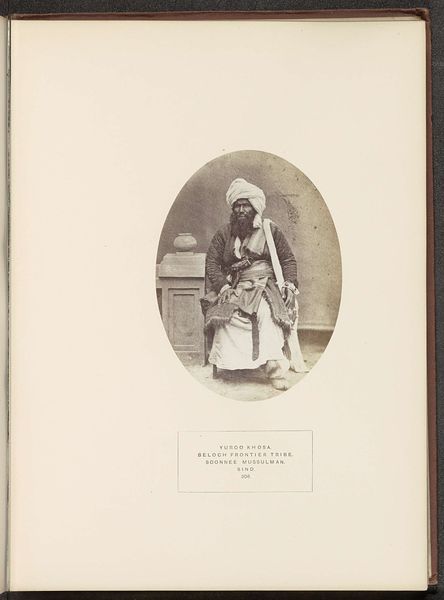

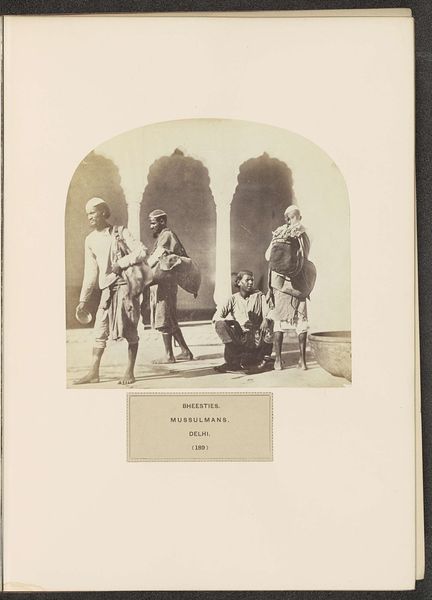

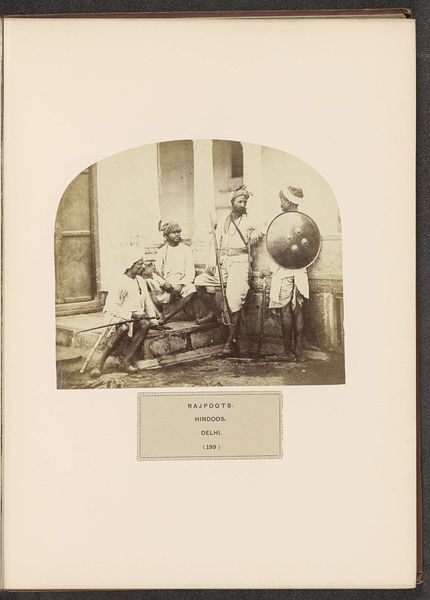

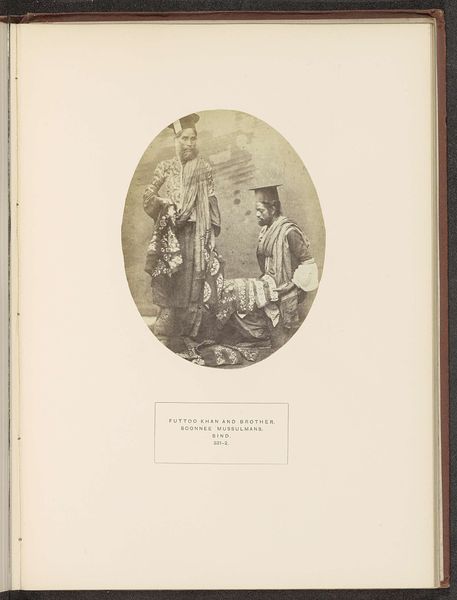

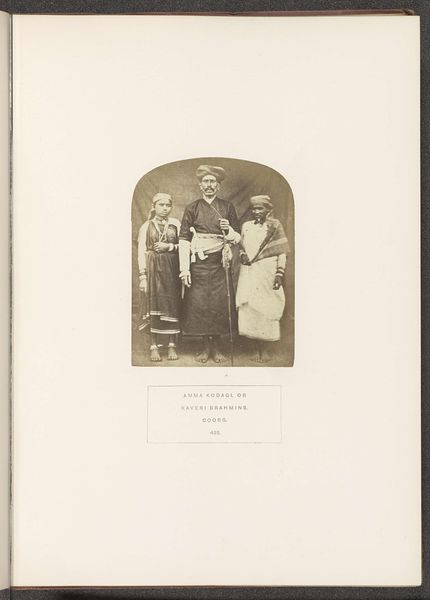

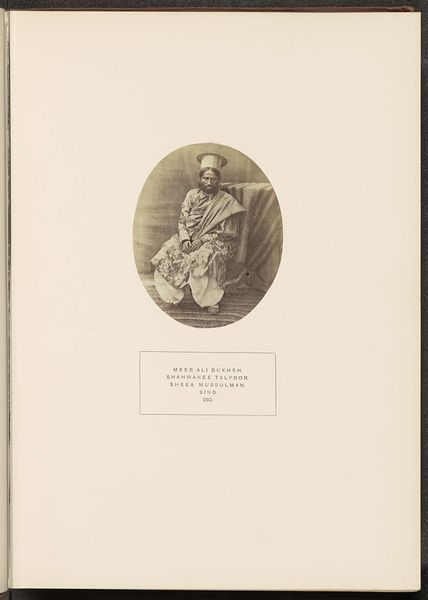

print, photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

# print

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

albumen-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 139 mm, width 96 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before you, we have a fascinating albumen print titled "Portrait of Ali Khan and a Servant," taken sometime before 1872 by Henry Charles Baskerville Tanner. Editor: The subdued sepia tones immediately give it an antique feel. The men’s expressions seem formal, posed—almost stiff. I’m curious about the social dynamic here; what story is this photograph trying to tell? Curator: Contextually, these photographic portraits were often commissioned by British administrators and other colonial officers as a means of documenting the local populations and dignitaries. It represents a fascinating tension. On one hand, a genuine effort for the Empire to represent different parts of the world. Editor: Exactly. The portrait presents a specific view of power dynamics in colonial India, which makes me question who held control. Ali Khan stands, and the servant kneels, and that sort of immediately clues the viewer into social hierarchies of the time. Even the carefully constructed composition, it speaks of Westerners controlling the means of image-making for others, with particular ways of framing, and ultimately presenting, power relationships between colonized peoples. Curator: Indeed. The work itself contributes to the construction of the "other." Ali Khan is exoticized in the gaze of a colonizer—a Western audience keen to categorize and collect representations. It shows their life through what the empire and administrators wanted others to see and believe. This sort of photo played an active part in defining cultural stereotypes of different populations in society. Editor: Looking closely at the clothing and adornments becomes important. Details on their fabrics might signal specific markers of status, perhaps regions. They should be considered symbolic beyond just decoration and really speaks to cultural context. How do such aesthetic decisions speak volumes about societal norms and identity? Curator: Ultimately, analyzing photographs like this requires that we are critically aware. They document visual information but, above all, reflect a society’s culture and what sort of gaze controls the means for representations. Editor: Right, seeing beyond surface-level "realism" lets us grasp what this photograph is doing culturally. A look beyond historical records and into how those records were created—it’s unsettlingly thought-provoking.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.