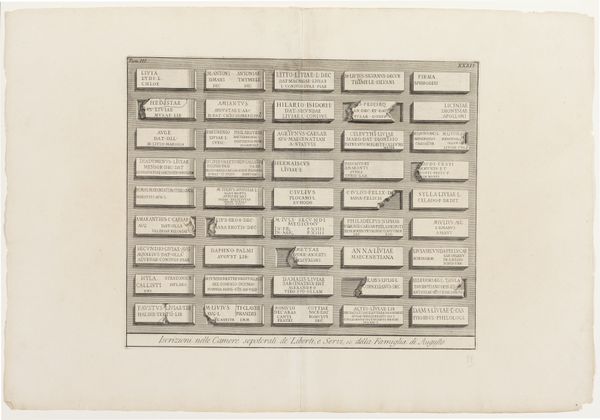

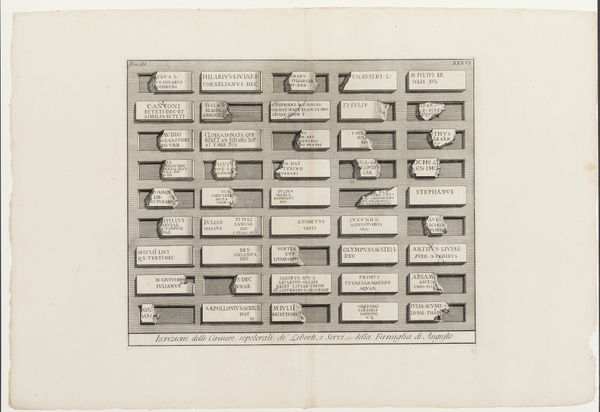

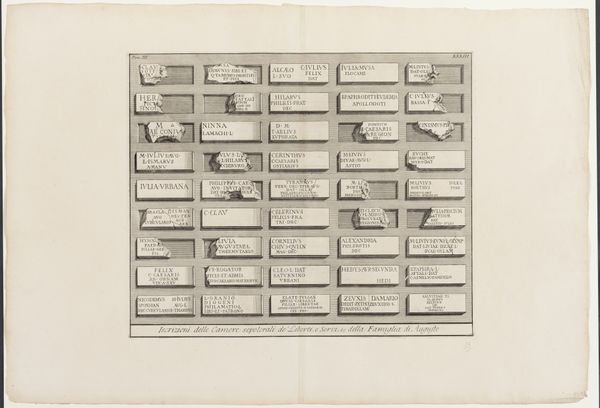

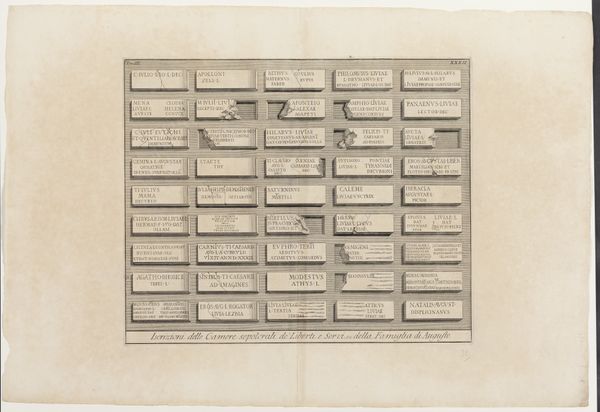

graphic-art, print, engraving

#

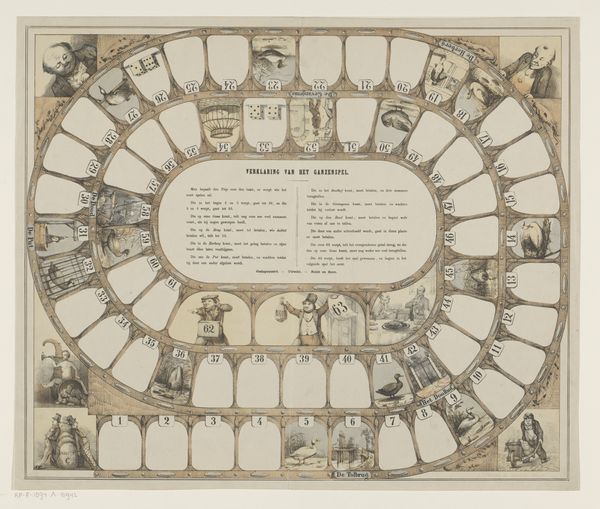

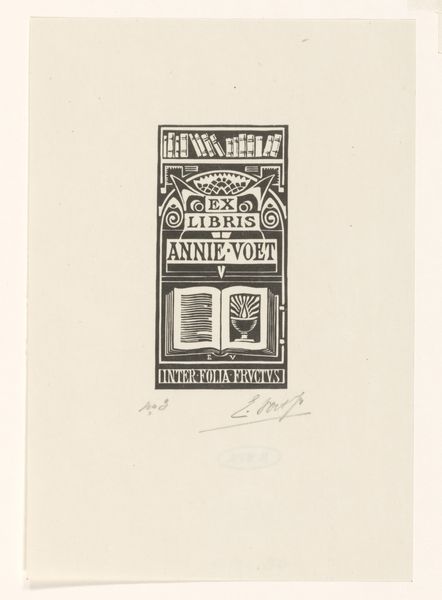

graphic-art

#

comic strip sketch

#

light pencil work

#

shading to add clarity

# print

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

pen-ink sketch

#

pen work

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

#

sketchbook art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 211 mm, width 282 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

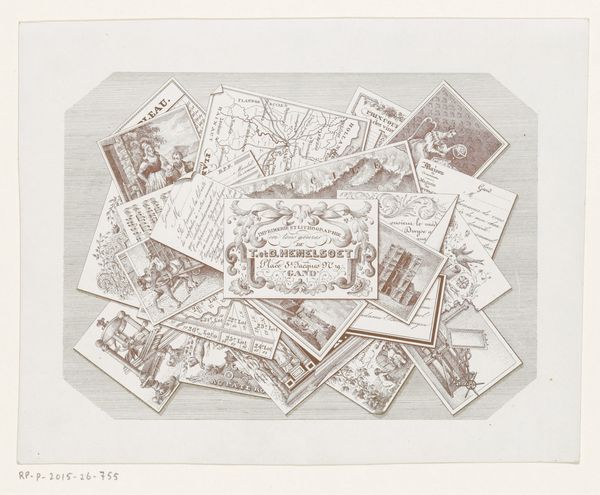

Curator: This print is titled "Kalenders voor 1835, uitgegeven door Henri Gache te Parijs" created around 1834-1835 by Émile-Eugène Lesaché. It’s a fascinating collection of what seem to be calendar pages, all emanating from a central publisher’s announcement. What’s your initial take on it? Editor: It has an almost chaotic, collage-like quality, yet there’s a definite order. The overlapping calendars remind me of stacked papers on a desk. How do you interpret this layering of time and information in the context of 19th-century Paris? Curator: Precisely. Consider the rise of print culture at the time. This piece embodies the explosion of accessible information and the democratisation of knowledge. What does it mean for Henri Gache to place his name so centrally amidst all these calendars? Isn’t it about controlling and structuring people's very perception of time, of orchestrating their daily lives through his publications? The printing press was integral in changing political and social narratives... where do you see it represented here? Editor: That's interesting, like he's not just providing a tool, but also shaping the entire temporal experience of the user. But how does the image of the calendars themselves reinforce those societal influences? Curator: Think about it. These calendars likely include information relevant to the French bourgeoisie. Are they meant to shape work, leisure, religious practice, cultural identity? It's also a method to engage with visual literacy as more calendars contain visual elements. The engraving as a whole speaks to the burgeoning culture and economy emerging, even today we consume similar images, just digitally! How do you feel knowing the origin now? Editor: It reframes how I look at contemporary trends and how easily we take certain formats for granted. Seeing the beginning grounds us and gives everything new perspective. Curator: Exactly! Context is always key to interpreting art. We began to uncover that the artwork's artistic intent extends beyond just creating aesthetic content and invites inquiry and a much wider socio-historical analysis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.