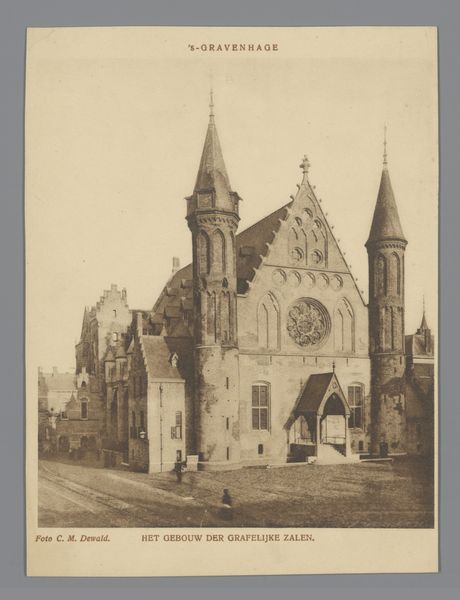

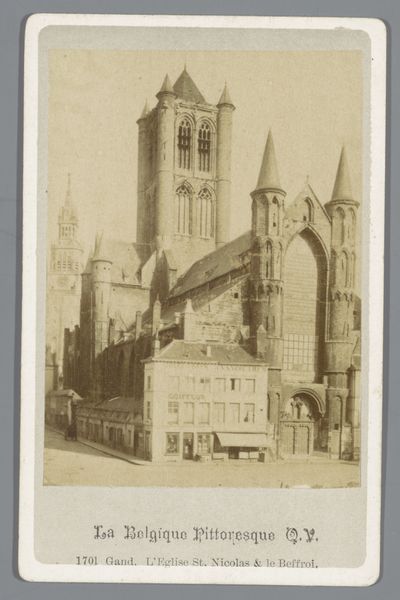

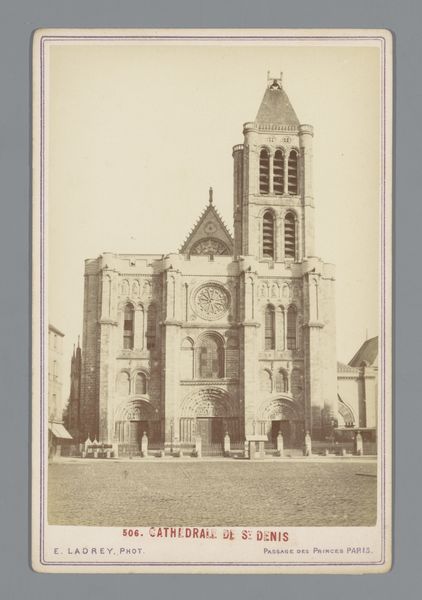

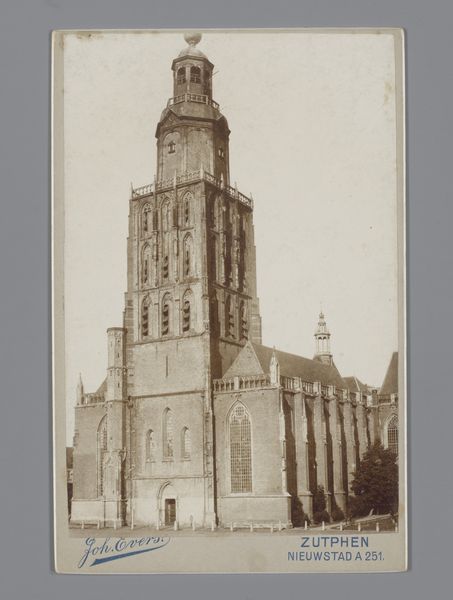

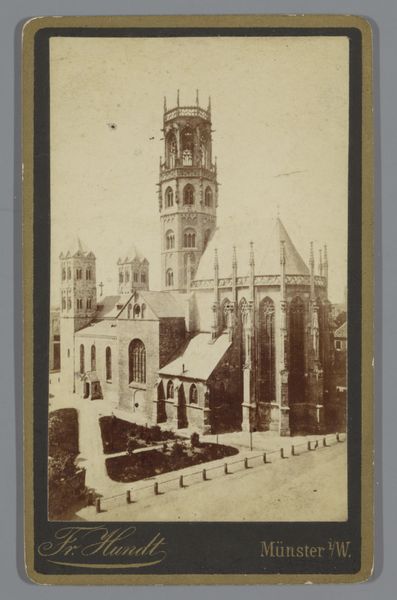

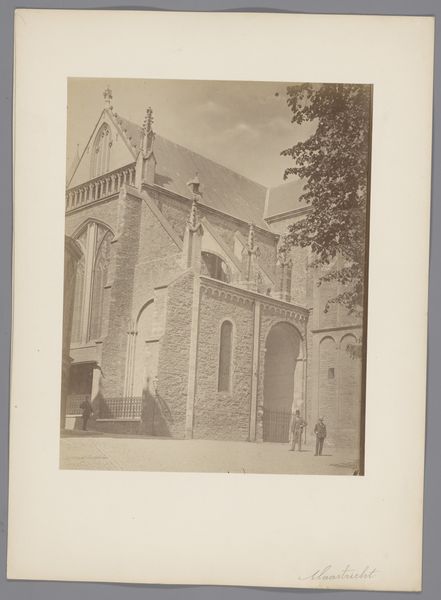

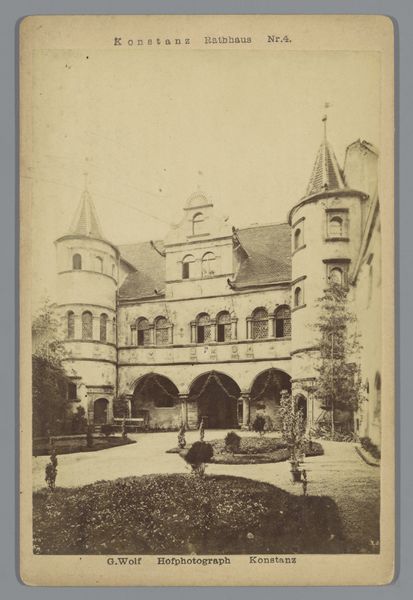

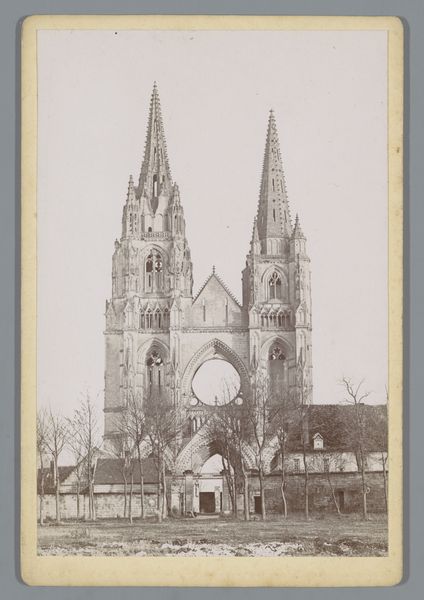

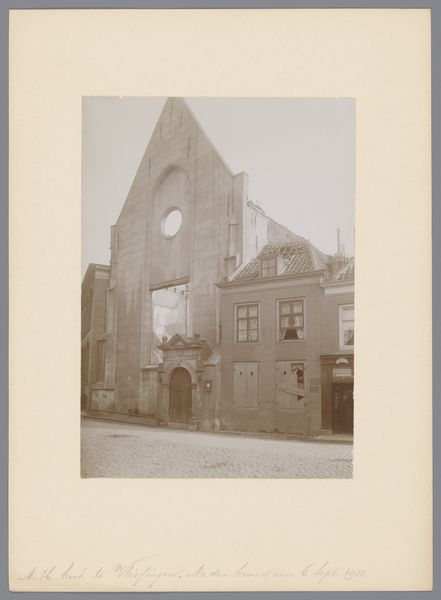

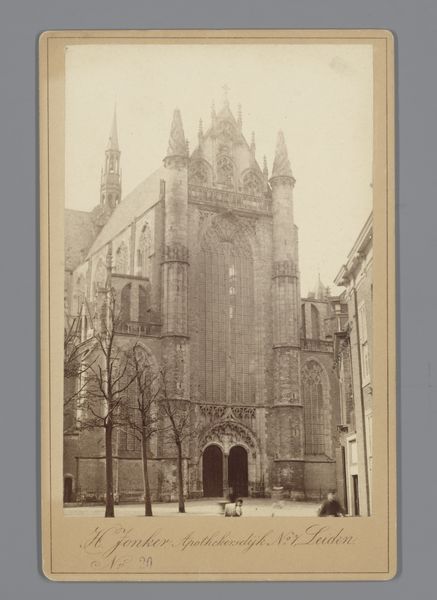

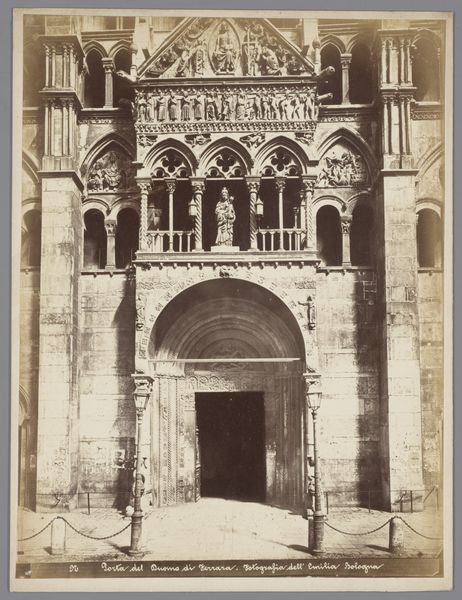

print, photography, architecture

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

historic architecture

#

photography

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

architecture

#

realism

Dimensions: height 178 mm, width 201 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a photographic print titled "Gezicht op het stadhuis van Veere, 1743" attributed to Jan Caspar Philips, though it was actually created around 1747. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. What's your initial response to this cityscape? Editor: There's a somber quality, isn’t there? It’s not just the sepia tone, but the overall quietude and stillness of the scene. It’s like the building is holding its breath. It gives me an eeriness like looking back into the old days. Curator: That stillness you observe speaks to the burgeoning development of photography and its application. Before the modern age, architecture photography such as this helped urban planning and property sales, as well as the more cultural objective of historicizing a moment in time. The figures in the print aren’t candid, but staged to illustrate its true size. Editor: Absolutely. Staged… Almost like players on a stage. It makes the town hall feel almost like a stage set. I find myself drawn to the sharp lines of the geometric design versus the gentle fade of what I assume is time, on the photograph. Does the work’s apparent realism suggest anything more specific about this era of printmaking and architecture? Curator: Yes, and realism was prized, but it had to be created from reality first! What the photograph does is to record social relationships as expressed through this particular architectural presence and space of commerce, government, and public interaction. Editor: Hmm… so almost less about aesthetics, more about showing folks exactly what the heart of Veere actually *was*, huh? Sort of taking a picture for grandma, “wish you were here”, while, in practice, recording for property’s sake and tax purposes? Curator: To an extent, though photography allowed the middle classes an easier path to art ownership than painting and more traditional portraiture. A photograph like this allowed new forms of looking to coalesce as a symbol of progress itself, which could also bring nostalgia and peace, but in some cases anger at where the city or town's path was headed. Editor: Looking at it now, knowing its various applications—historical record, sales tool, early adoption in the fine art sector—it transforms before my eyes. It seems more significant. Like a silent document about an economy in transition. I see new depth. Curator: Exactly. It makes you realize the power that photographic and print-making technologies played. Thanks for giving us your insight, it was really interesting to dissect the material nature of what is pictured, in addition to its value as an object.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.