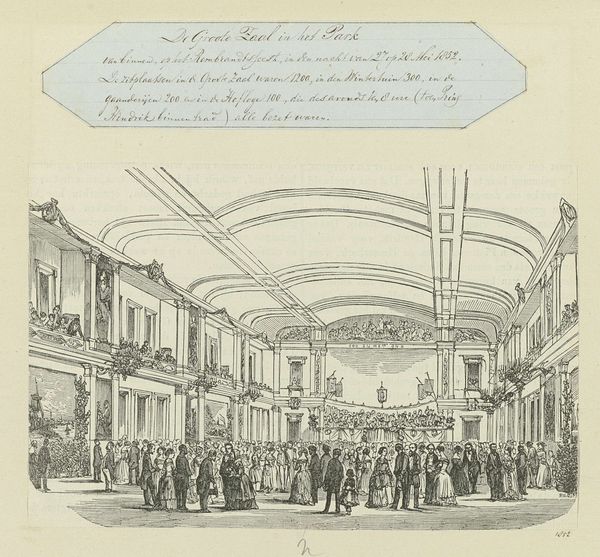

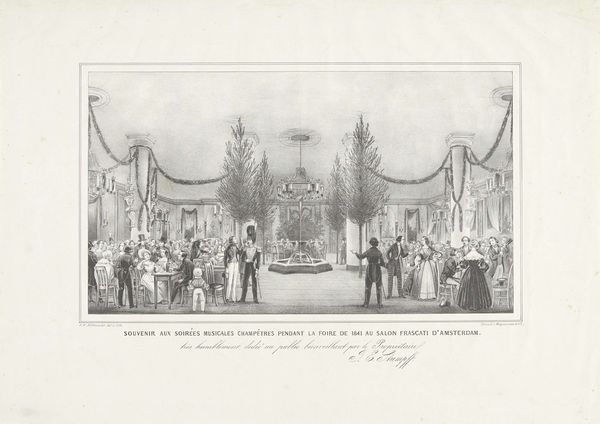

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 270 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Zaal in Frascati," an engraving made by Carel Christiaan Antony Last in 1854. It resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first impression? It's like stepping into a memory, a crowded room buzzing with…something. The scale is disorienting, though. It feels vast, but the people are tiny. Curator: Vast, but intimate. This engraving depicts a scene inside Frascati, a well-known establishment in Amsterdam during that era. A space buzzing with life and commerce. Editor: It's all in the line work, isn’t it? Look at how dense the figures are rendered compared to the more open, flowing lines detailing the architectural ornamentation. Almost as if the labor of rendering those figures emphasizes the figures’ existence as materials. Curator: Absolutely, and the style blends romanticism with realism. The artist wasn’t just interested in showing a crowd; it’s the depiction of a very specific moment, a snapshot of social life and the interior architecture of the Frascati during its heyday. You know, the artificial trees are pretty funny... they could have used the real thing! Editor: Exactly. Speaking of architecture, those ornate ceilings and the lighting fixtures! All made to impress, to consume. And notice how the architecture towers over and dwarfs its inhabitants. The architecture material dominates their labor! Curator: And consider what's *not* there. This is during the rise of industrialism; perhaps Last hints subtly to how architecture has begun to compete for importance in daily life? I also can’t help but sense the artist's fascination with history painting seeping through. Aren't the statues more alive somehow? Editor: It is difficult for a painting of any period to transcend into "history painting." More, this artist seems rooted in depicting current reality. Although they use romanticism, architecture, materials, and methods available at the time. Curator: It certainly raises a question: do the romantic inclinations obscure the deeper exploration of social dynamics? Or does that just reveal more layers of perspective to an era we continue to consider as simply "bygone"? Editor: Well, looking at the etching medium itself adds to the layers. An image, reproducible en masse for an increasingly literate and visually hungry public, itself becomes another commodity… it mirrors the interior architecture of that Frascati hall, really. The same intention—impress and inspire and sell! Curator: Fascinating—so in the end, Last is almost a witness to this consumption... creating something itself easily consumed, by the wider public. I didn't think of it that way. Editor: In a way, he is not just the recorder, but an instrument, or more, a building-block—material—in the very engine of commerce itself! What’s so striking about materialist takes on images and art generally, right?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.