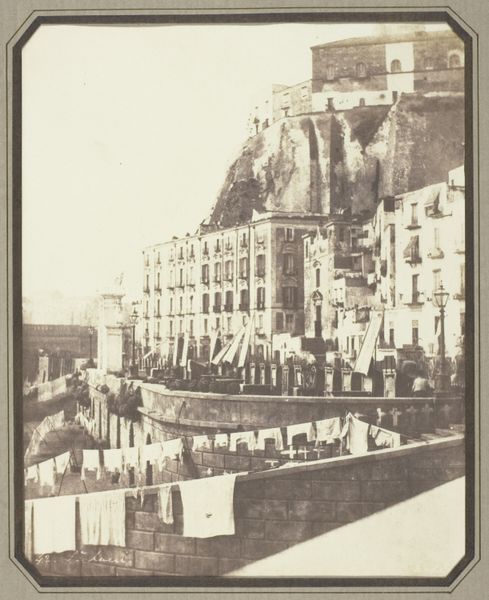

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

architecture

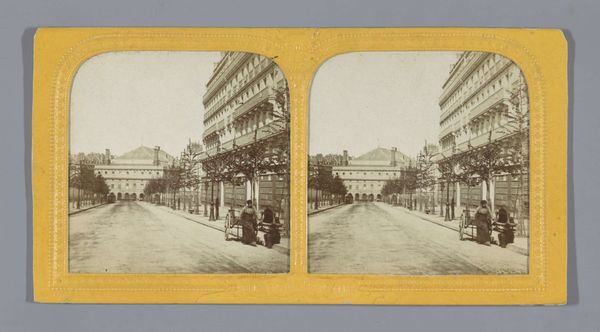

Dimensions: 22.4 x 36.2 cm (8 13/16 x 14 1/4 in.) overall Image: 22.2 x 17 cm (8 3/4 x 6 11/16 in.) each

Copyright: Public Domain

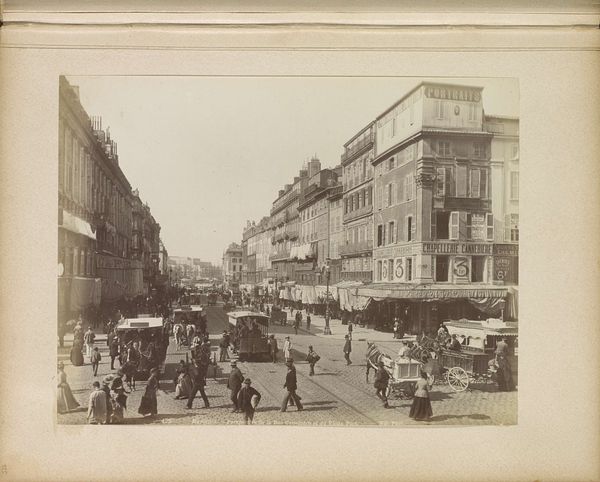

Editor: So this is Calvert Richard Jones’ “Santa Lucia, Naples,” a daguerreotype from around 1845. What strikes me is the everyday activity captured, like laundry hanging out to dry, in what we think of as this early, kind of monumental photography. What do you make of that juxtaposition? Curator: Precisely. This image encapsulates a pivotal moment in art history where technology meets social reality. Consider the labor involved in producing a daguerreotype – the careful preparation of the silvered copper plate, the long exposure time, and the subsequent development. Then juxtapose that with the labor visible in the scene: the mundane task of washing clothes, a chore likely performed by women from the working class. It forces us to acknowledge the relationship between artistic production and everyday life. Editor: Right, I see what you’re saying. It almost brings it back down to earth. The scale of the city seems less imposing when it's populated with the signs of daily routines. Do you think that contrast was intentional? Curator: It's less about the artist's intention and more about the unavoidable constraints of the medium and the social context. Long exposure times meant capturing static scenes – architecture and landscapes, yes, but also the slower rhythms of daily life. It inevitably captured elements that romanticized paintings might have excluded. Editor: Interesting. It almost feels like a documentary approach then, not striving to elevate the subject matter above its working-class reality. Curator: In a way. Photography democratized image-making, moving it, even unintentionally, away from solely elite artistic concerns and opening it to the lives and labor of a wider spectrum of society. We should notice here that access to photograph such a panorama suggests social mobility afforded by the early industrial context, in that early middle period where it was novel enough to capture, yet somewhat available to the entrepreneurial class to access it. Editor: I never really considered it in terms of democratization, and linking photographic practices with social observations is a fascinating perspective that really changes my appreciation of this early photograph. Curator: It invites us to re-evaluate the power dynamics inherent in representation and the very means of artistic production itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.