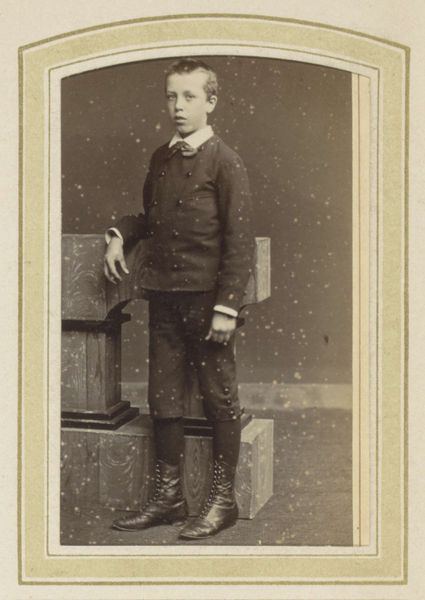

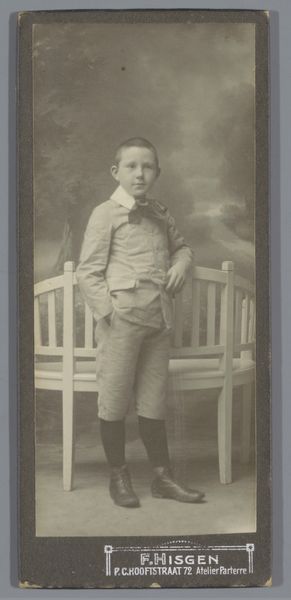

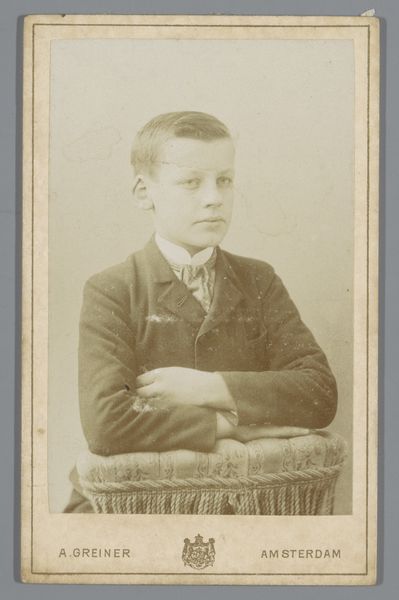

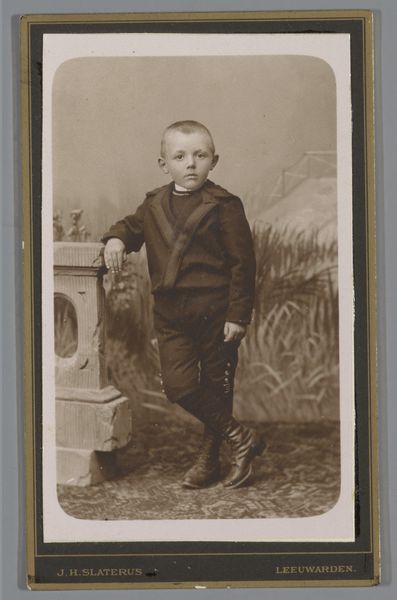

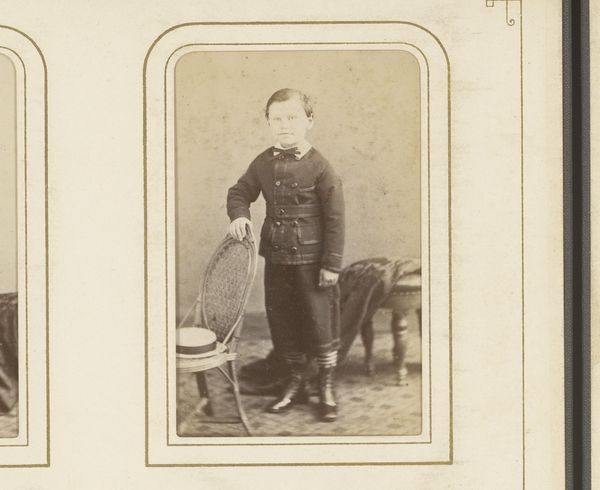

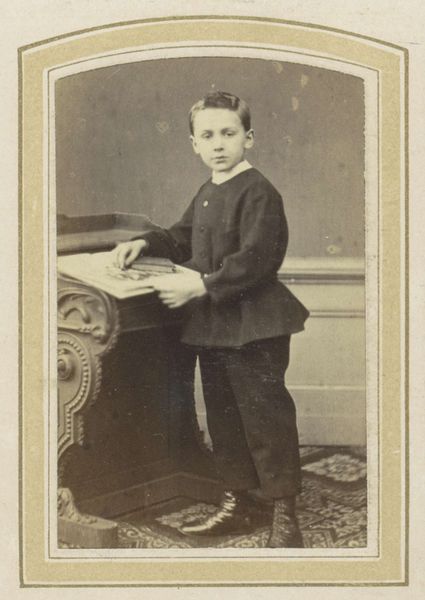

Portret van een jongen met een boek op een tafel, met op de achtergrond een sokkel 1860 - 1905

0:00

0:00

photography, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

book

#

photography

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 83 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is an albumen print by Jan Goedeljee, titled "Portrait of a Boy with a Book on a Table, with a Pedestal in the Background," dating from sometime between 1860 and 1905. The boy's gaze is intense, almost unsettling. It makes me wonder about childhood during this time. What strikes you about this image? Curator: It's fascinating how portraiture like this served a critical social function. Photography in the late 19th century democratized portraiture, but also standardized it. These weren't just pictures; they were status symbols. Think about it – who was commissioning these images, and why? Was it simply documenting a child's likeness, or conveying a certain image of the family? Editor: So, you’re saying it’s less about capturing the boy’s true personality and more about projecting an ideal? The book, for example—is it about actual learning, or merely an accoutrement of upper-class life? Curator: Precisely! Notice the staged quality—the potted plant, the backdrop. These elements aren't incidental. They signify cultivated taste, prosperity, and access to education. It’s a carefully constructed performance for the camera. Consider who this image was *for*. Albums were public displays within the home, intended to reinforce social standing. The circulation and display is essential to its meaning. Editor: That adds a whole new dimension. It’s not just a portrait; it’s a form of social communication. I never considered how “public” a family album actually was back then. Curator: And consider the boy’s somber expression, which was conventional, but what did this convey, and for whom? Does this represent some tension of image creation as well, or a new social construction of masculinity in that time period? Editor: This really makes me rethink how I approach historical portraits. It’s not enough to simply see the subject; you need to understand the entire social and cultural context in which the image was produced and consumed. Curator: Absolutely. Thinking about images this way transforms a simple portrait into a window into the complex social dynamics of the era.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.