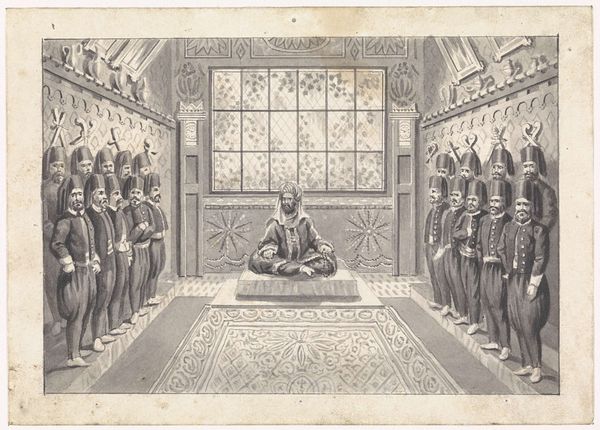

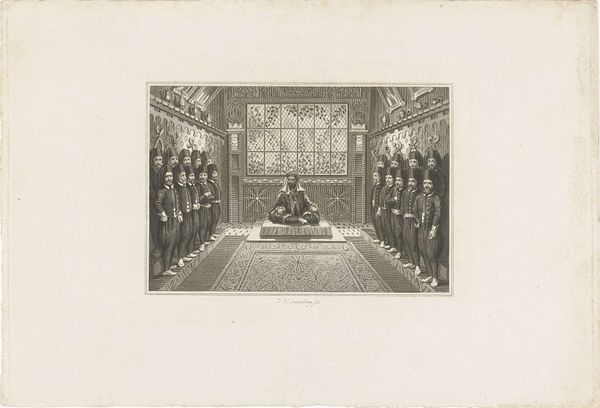

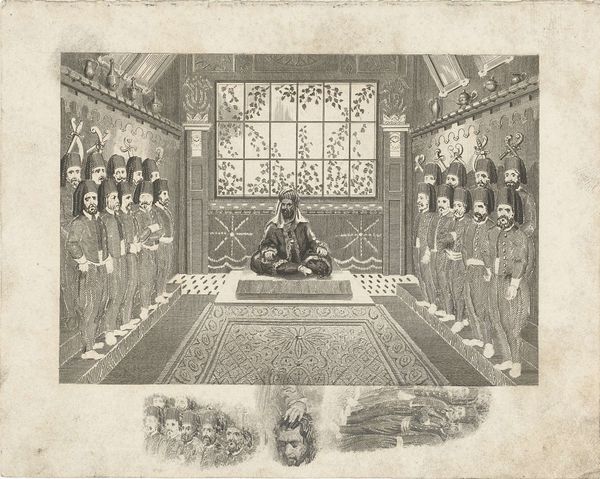

Man met tulband zittend in kleermakerszit en 19 soldaten die allen een fez dragen 1830 - 1845

0:00

0:00

henricuswilhelmuscouwenberg

Rijksmuseum

drawing, ink, pen

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

comic strip sketch

#

quirky sketch

#

sketch book

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

idea generation sketch

#

sketchwork

#

pen-ink sketch

#

orientalism

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

initial sketch

Dimensions: height 135 mm, width 175 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This drawing, in pen and ink, comes from the hand of Henricus Wilhelmus Couwenberg and is titled "Man met tulband zittend in kleermakerszit en 19 soldaten die allen een fez dragen," which translates to "Man with turban sitting cross-legged and 19 soldiers all wearing a fez". It dates from somewhere between 1830 and 1845. Editor: My first impression is a stage, meticulously set. The man in the turban radiates a still calmness, while the soldiers appear almost like identical props—interesting contrast. Curator: It's a fascinating example of Orientalism, a genre reflecting European artists' romanticized or stereotyped views of the Middle East and North Africa. Consider how power dynamics may be playing out, with the single, elevated man versus the regimented soldiers. Editor: Absolutely. The turban itself speaks volumes, marking the central figure's status, perhaps wisdom or spiritual authority. The fezzes on the soldiers create a sense of uniformity, a collective identity willingly assumed. The repetition serves to diminish individuality in favor of group belonging. Curator: That uniform appearance echoes contemporary military trends in Europe at the time. What seems exotic on the surface might reflect European socio-political fascination with control and order, projected onto the "Orient." The question, though, is what purpose did it serve. The drawing feels very private. Editor: Notice the interior details - a floral, ornamental motif repeated within the room, hinting at opulence and exoticism, common themes within Orientalist works. They represent something greater about both class, but a fascination of culture as seen from abroad. Curator: Exactly, the drawing's public life would then perpetuate specific perceptions of those cultures back in Europe through these artistic choices. Think of it as cultural dialogue—albeit potentially flawed and certainly biased—conducted via artistic representation. It certainly evokes larger conversations of art’s purpose as either reflection or a driver of public sentiment. Editor: The visual language it utilizes—the turban, the fez, the setting—acts as cultural shorthand. As an audience, we need to unpack those loaded symbols carefully, recognizing the image may perpetuate certain stories. Curator: Thank you. Editor: Indeed, thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.