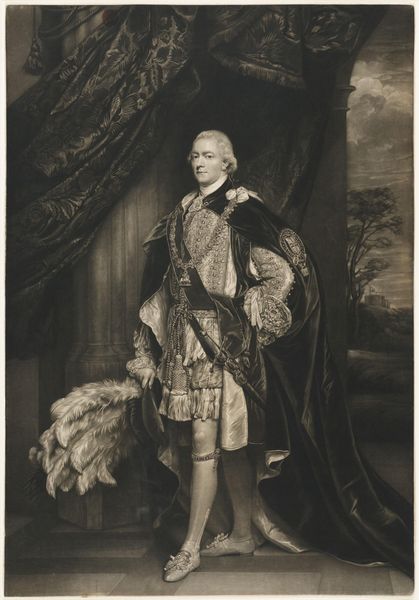

Portret van Hendrik Frederik van Cumberland en Strathearn 1774 - 1775

0:00

0:00

thomaswatson

Rijksmuseum

Dimensions: height 616 mm, width 387 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: So, this print by Thomas Watson, dating from about 1774-1775, depicts Prince Henry Frederick, Duke of Cumberland and Strathearn. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, what strikes me is this contrast between the opulence of the Duke’s attire and his rather blank, almost forlorn expression. It’s a really curious emotional discord. Curator: That's a fascinating observation. His clothing is clearly meant to convey status—the robes, the insignia, the feathery hat—but you’re right, there’s a distinct lack of warmth or genuine presence. It’s a very stylized representation, conforming to conventions of aristocratic portraiture. Editor: Absolutely, the symbols are almost shouting for attention: The architecture framing him speaks of power, and even the landscape painting seems like a carefully curated backdrop. Do you think this level of staging hints at a certain…insecurity, perhaps? A need to over-emphasize the external markers of his rank? Curator: Perhaps. Or maybe it speaks to the role that portraiture played at the time: less about capturing the individual soul and more about solidifying a dynastic narrative. Note, too, how precisely rendered his garments are—Watson excelled in capturing such textures using the engraving technique. Editor: And textures themselves carry symbolism, don't they? The sheen of his robe, the fluffiness of the feathers… they all amplify the Duke's visual "worth". One wonders what stories the family crest and each individual medal could tell. The engraver seems quite deliberate in capturing the fall of light upon each object, which does hint to some personal touch embedded within tradition. Curator: Indeed. The play of light helps give a sense of volume and grandeur. The piece follows Baroque traditions, yet has a starker sensibility compared to earlier masters, signaling evolving aesthetics of nobility at this moment. It is also interesting to remember the context, which includes increased commercialisation of artworks, meaning such images where reaching wider audience that just aristocrats. Editor: It certainly provokes thoughts about how individuals and identities are fashioned – literally and figuratively. I wonder about Henry's feelings about being displayed this way, or who ordered such work? A puzzle to the soul and mind for our audience, isn’t it? Curator: A truly great visual record raises more questions than it answers, doesn't it? It’s in this ambiguity and careful deliberation of representation, this push and pull between reality and constructed image, that we discover fresh meaning each time we revisit it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.