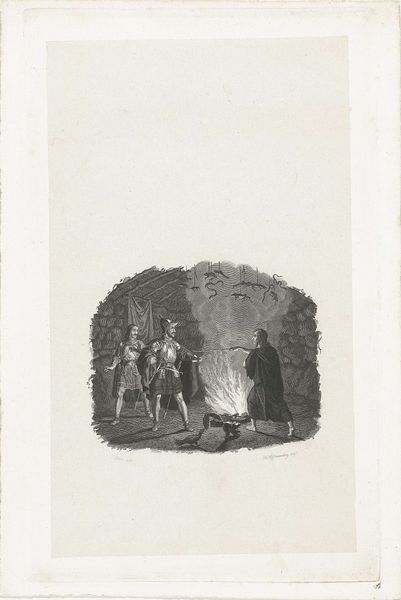

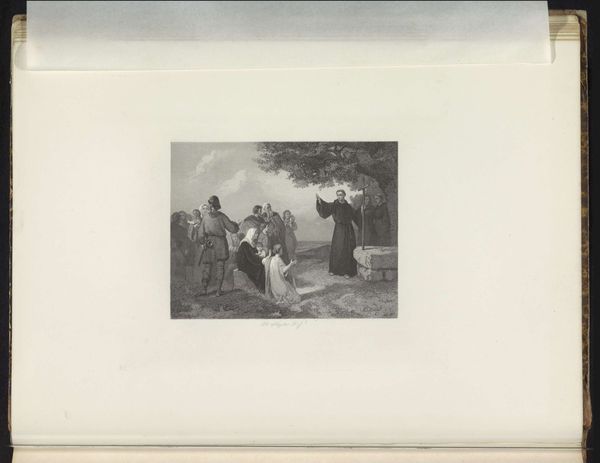

Hertog Arnold van Gelre door zijn zoon Adolf ontvoerd, 1465 1844 - 1846

0:00

0:00

johannwilhelmikaiser

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

medieval

# print

#

figuration

#

romanticism

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 238 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

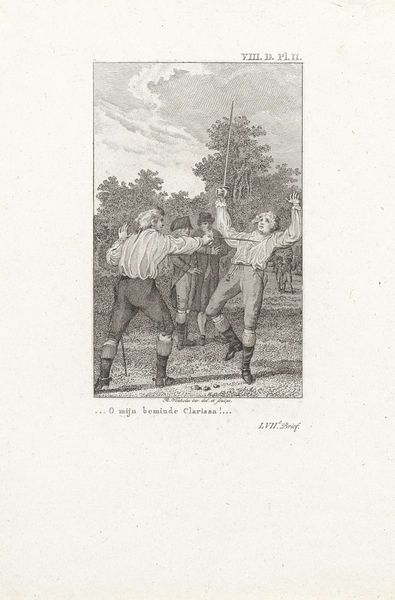

Curator: Before us we have Johann Wilhelm Kaiser's engraving, "Hertog Arnold van Gelre door zijn zoon Adolf ontvoerd, 1465," created between 1844 and 1846, here on display at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought? It's stark. The darkness is really oppressive, and the figures look so vulnerable on that icy expanse. The detail is quite striking considering it's a print, giving it a surprisingly textured feel. Curator: Indeed. The artist is depicting a historical event: Duke Arnold of Guelders being kidnapped by his own son, Adolf, in 1465. This print revives the Northern Renaissance interest in portraying morality tales through historical narrative. It was quite common in 19th-century Romanticism. Editor: Right, and look at the medium—engraving. It's a laborious, painstaking process, and really dictates the visual language. It allows for the creation of so many prints! Imagine the message and narrative spreading due to Kaiser’s material process. Curator: Precisely! And notice the strategic use of light. The torch not only illuminates the figures but throws stark shadows. Creating drama within this otherwise bleak and ethically dark scene. Editor: Definitely adds to the sense of unease. The figures are stiff. This could relate to a broader interest during this time of reinterpreting earlier periods via craft and print processes. You can almost feel the weight of the metal plate and the pressure exerted to make this impression. Curator: Moreover, prints like these played a critical role in shaping historical consciousness, in a sense becoming visual propaganda by the state as a collective visual memory was forming. Editor: A powerful tool for circulating stories and, as you say, solidifying collective memories. It makes me think about how printmaking democratized imagery to shape views on power, succession, and conflict through relatively reproducible means. Curator: Ultimately, this work functions as a powerful example of how 19th-century art engaged with history to explore themes of power, betrayal, and the fraught relationship between father and son. Editor: I'm still thinking about the sheer effort required to create this kind of print. Seeing it now, divorced from its original making process, it's good to recall how material circumstances profoundly influence historical and cultural expression.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.