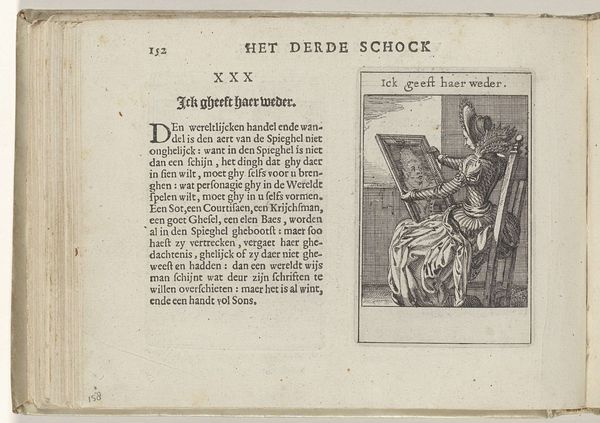

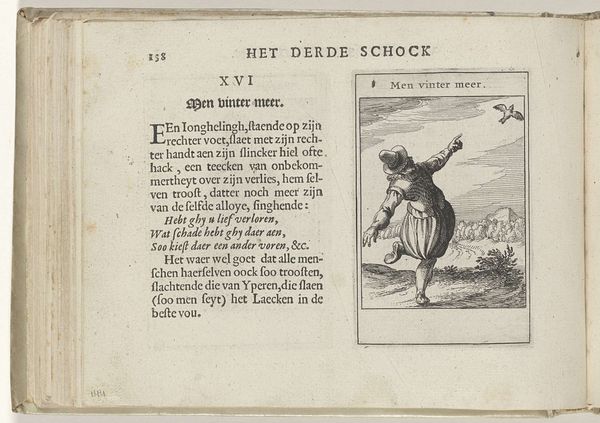

print, engraving

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 137 mm, width 188 mm, height 95 mm, width 60 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving by Roemer Visscher, dating back to 1614, is titled "XXXIV Hy leut diet leut ick en leut naet," currently housed at the Rijksmuseum. I am struck by the almost crude intensity of the mark-making. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of unease. The figure is unsettling, not only due to its strange proportions, with the small head, stocky body, and nudity, but because of its presentation alongside a dense block of text. It's an odd juxtaposition, creating a confusing, somewhat repulsive impression. Curator: Right, let's delve into the materiality. It’s an engraving, a process that inherently relies on precision, deliberate cutting into the plate to then transfer to paper. The image is printed beside typeset words; it points towards the intersection of textual and visual culture and, importantly, labor and production techniques of that period. How would its meanings shift in an etching, lithograph, or digital rendering? Editor: I am wondering how contemporary audiences received this piece? The image seems to engage with the perception of monstrous or ‘othered’ bodies, particularly within the context of colonial encounters and exploration. The Dutch quote reinforces a societal tendency of seeing the East through a barbaric, uncultured lens, contrasting that perceived “monster” with the contemporary voyagers “who went everywhere”. Curator: Exactly! The print points to the constructed nature of the self and 'the other,' particularly in an era when Dutch maritime power was expanding and encountering diverse populations. What the image includes—or pointedly leaves out—is key in the way those colonialist notions spread into popular imagination via material circulation. Editor: Agreed, the monstrous figure acts as a focal point for anxieties about encountering unfamiliar cultures and the justification of exploiting “others”. It is particularly interesting in contrast with Dutch Golden Age masterpieces like "The Night Watch," a celebration of power through grand portraiture, this image presents the dehumanized product of a budding global network of trade and exploitation. Curator: Considering the material context of its making, one wonders whether the intention of the image and quote aimed to provoke such reactions in its own time. Editor: It feels important to continually question the ways artworks reflect, participate in, or critique systems of power, be they expressed visually or textually, in the present or the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.