Copyright: Public Domain

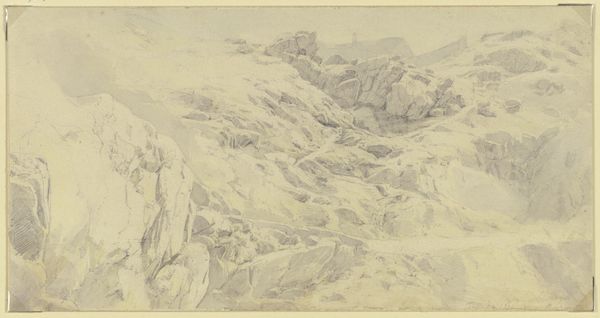

Curator: Welcome. Before us, we have Ludwig Metz’s 1852 pencil drawing, "Der Monte Serone bei Olevano," currently residing at the Städel Museum. Editor: It has a hushed quality. Soft and grey. The gentle lines lull you into a pastoral dream, doesn’t it? Curator: The artist masterfully uses delicate strokes to build form and spatial depth. Notice how the values shift to create light and shadow, particularly across the mountain range. Semiotically, the pencil work serves as an index of both mark-making and temporality. Editor: Right. But look at this place… Olevano, Italy. In the mid-19th century, the allure of the Italian landscape resonated deeply within artistic circles—a place where Romantic ideals met nascent Realist aspirations. I wonder what specific experiences and cultural encounters fueled the artist. It’s also critical to remember, who exactly was free to roam and make art there? Curator: His ability to represent tonal values contributes to this pictorial illusionism. Consider the distribution of elements—how each component guides the viewer's gaze across the scene. It is structured by pictorial concerns relating to positive and negative space. Editor: Certainly. But beyond structure, think of the landscape tradition. Historically, depictions of landscapes also served ideological purposes—often glorifying power and territory or romanticizing nature to erase or overshadow histories of land exploitation, dispossession and colonialism. I ask again: Who exactly is afforded this “pastoral dream?” And at what cost? Curator: His treatment presents an evocative vision, yes. Editor: Yes. One infused with social, political and historical undertones we should consider. Thanks for sharing this, the social underpinnings deserve further analysis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.