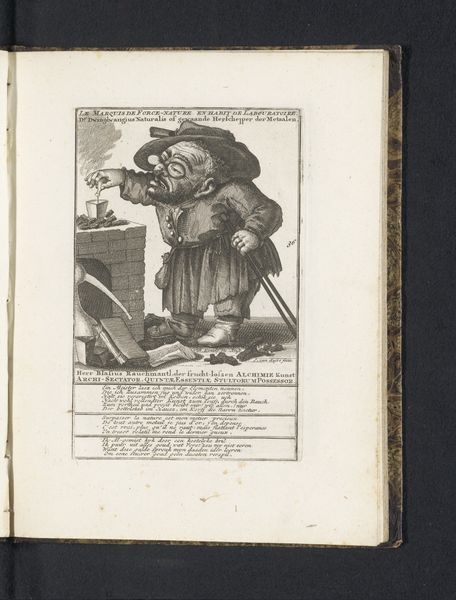

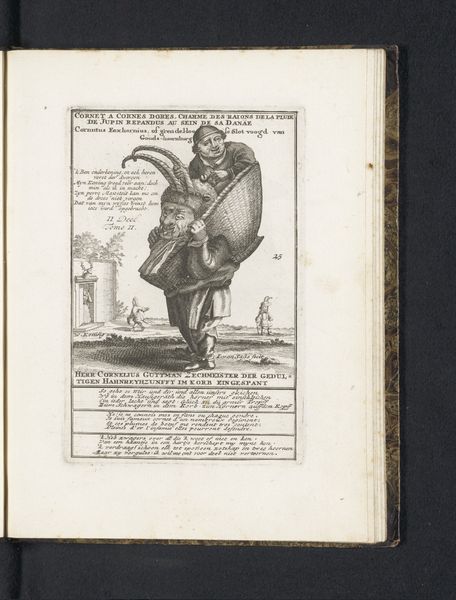

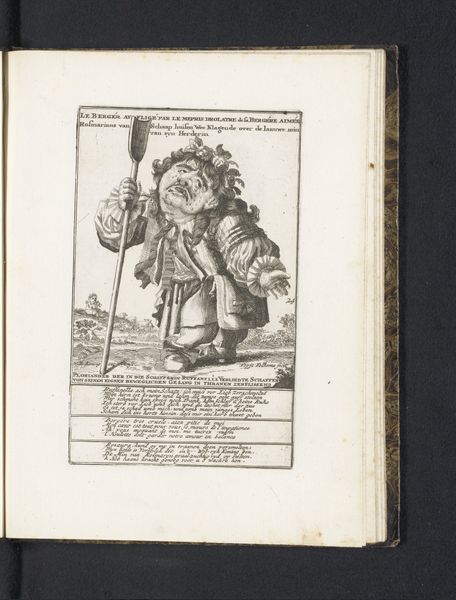

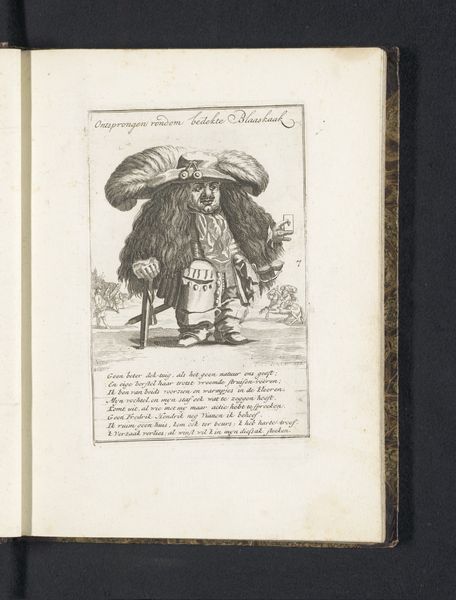

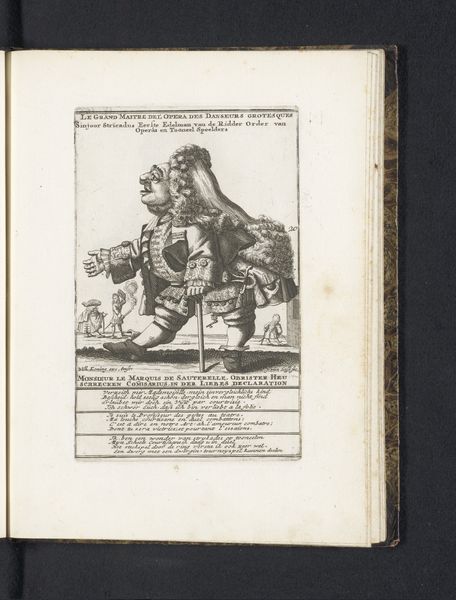

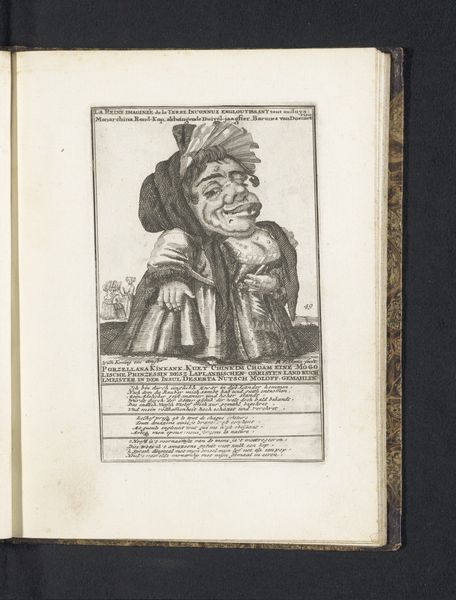

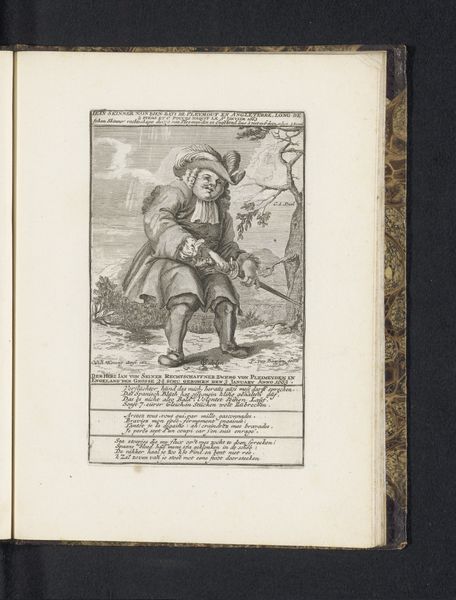

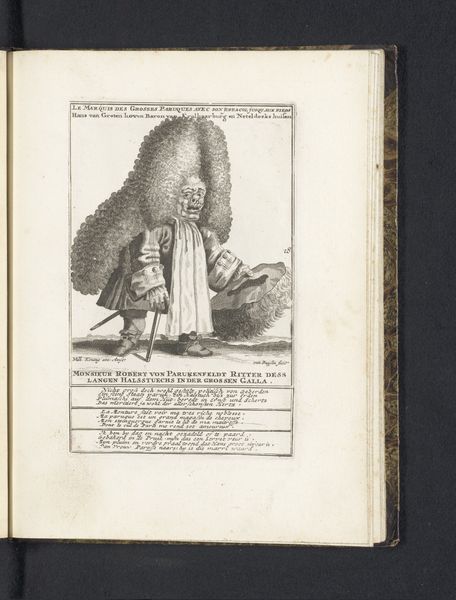

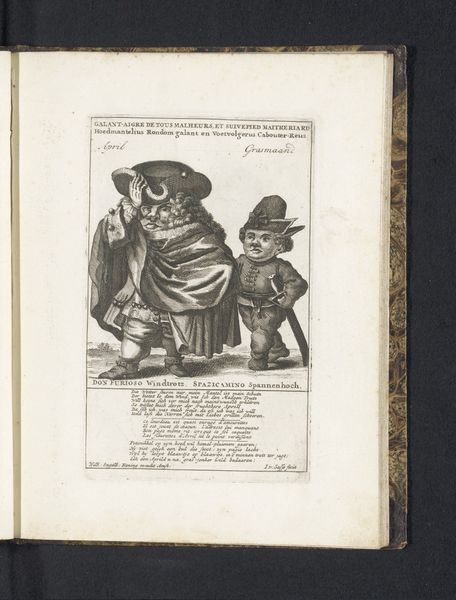

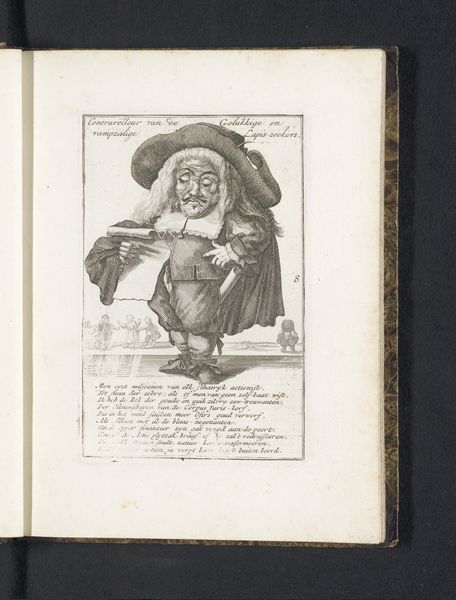

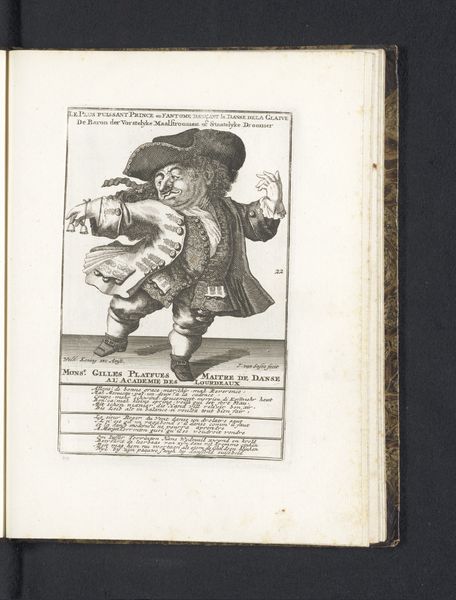

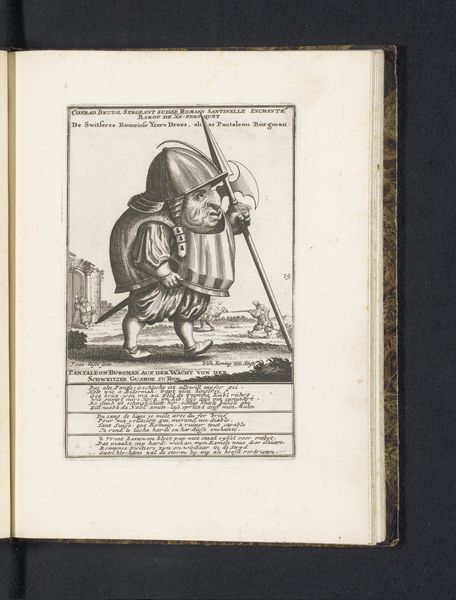

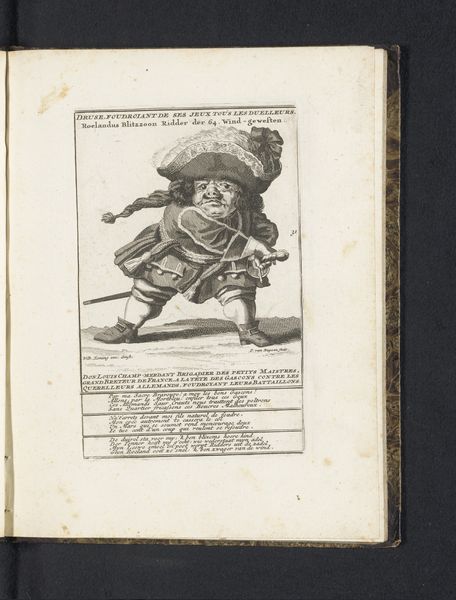

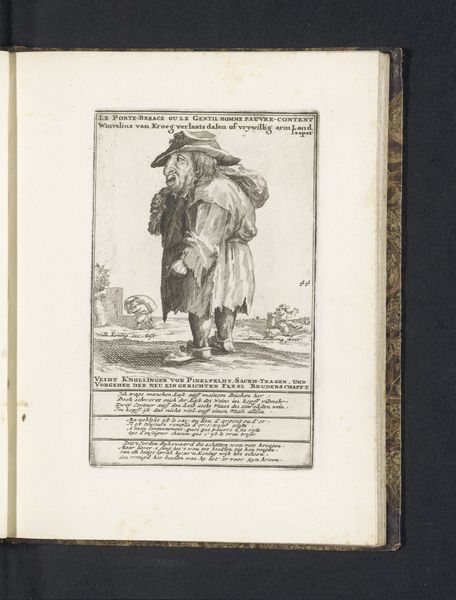

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 105 mm, height 227 mm, width 170 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving dating from between 1718 and 1720, "De dwerg Gewaande Pelgrim als pelgrim uit Compostella, 1720" or "The dwarf Self-proclaimed Pilgrim as a pilgrim from Compostella", created by Isaac Ledeboer. What strikes you first about this print? Editor: It’s immediately humorous, almost grotesque. The figure’s proportions are exaggerated, with the large head and beard dominating the composition. There’s a satirical bite to it that intrigues me. Curator: Absolutely. Ledeboer masterfully employs symbolic language. The pilgrim's garb, laden with scallop shells indicating pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela, is rendered almost comically. Each item carries a charge; for instance, note the gourd, traditionally used for carrying water, hinting at a spiritual journey. Editor: But is this commentary aimed simply at religious devotees, or is something else at play? The figure’s small stature, described as a "dwarf" in the title, seems significant. Could the artwork be commenting on the perceived inadequacies or hypocrisies of those in positions of religious authority? Curator: Precisely. It seems to reflect a wider critique prevalent during the Baroque period, specifically the performative aspect of religious devotion. Look closer, and you'll find layers of socio-political commentary beyond the surface depiction of a pilgrim. The inscription mocks supposed hypocrisy with labels in a variety of languages to reach an international audience. Editor: This also raises the question of audience. Was this intended for public consumption, or perhaps for a more limited, educated circle capable of grasping the layered irony? The relatively small size of the print suggests intimate viewing, but the textual annotations widen its appeal. Curator: Good point. Printmaking democratized imagery during that era. Multiple impressions made art accessible beyond the elites. Prints could be readily disseminated through various channels to promote widespread, sometimes subversive social commentary. Editor: Thinking about today, it's interesting to consider how this image—originally intended to criticize the appearance of religious dedication—could speak to the idea of authenticity versus superficiality. Curator: I think the image resonates because symbols retain power, irrespective of historical context. That inherent charge creates a kind of echo chamber through collective memory. It reminds us to question assumed images and encourages more informed readings of faith, power, and personal identity. Editor: It truly demonstrates the continuing influence that a deceptively simple artwork can have on understanding social attitudes, beliefs, and power structures from centuries ago, right up to the present day.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.