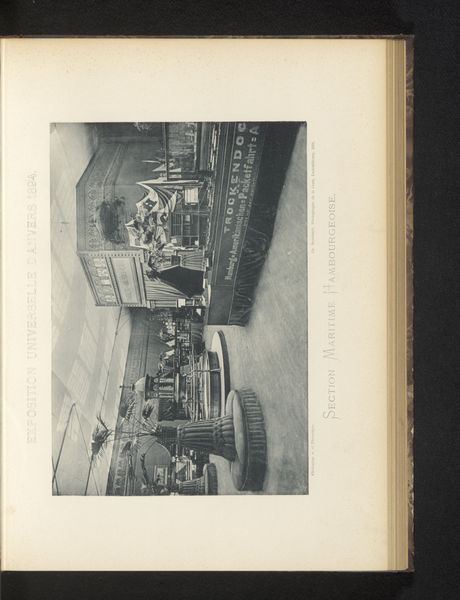

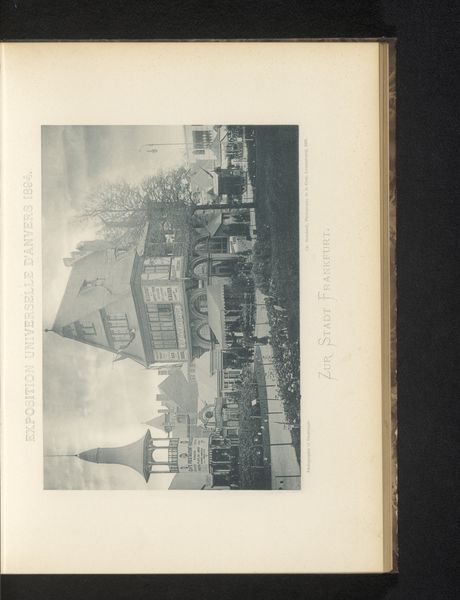

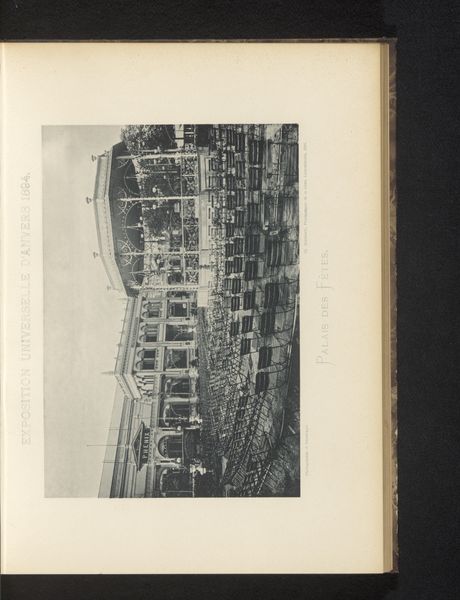

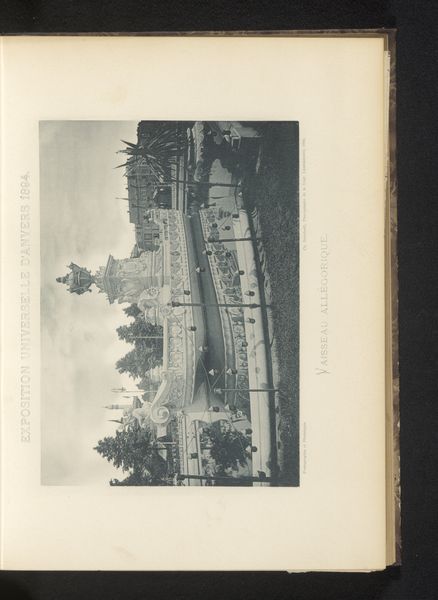

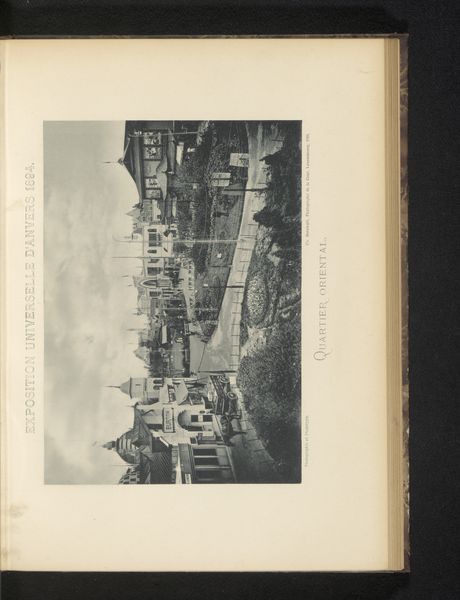

Gezicht op het Marokkaanse deel van de Wereldtentoonstelling van Antwerpen in 1894 1894

0:00

0:00

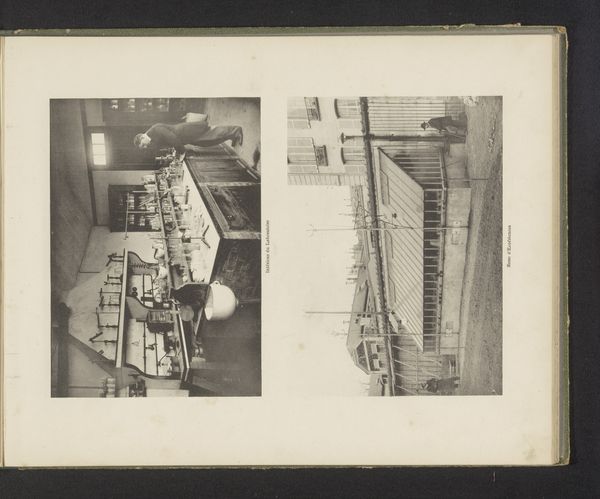

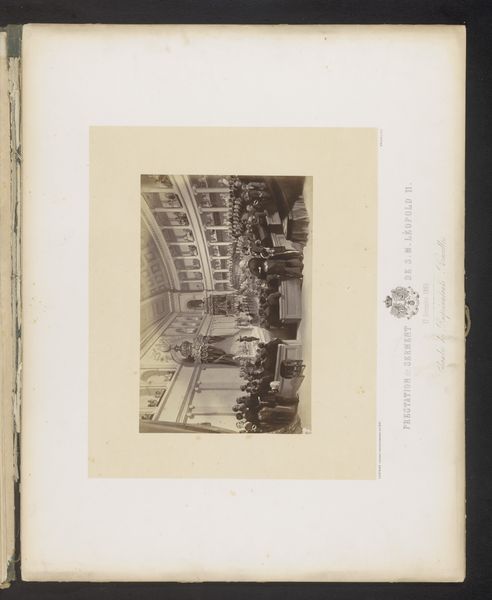

print, photography, albumen-print

#

art-nouveau

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 154 mm, width 222 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

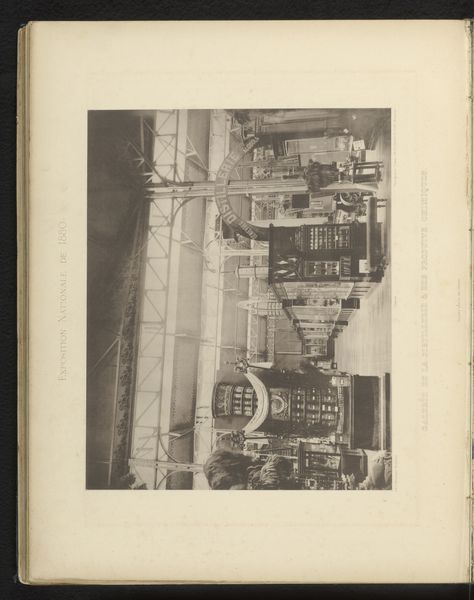

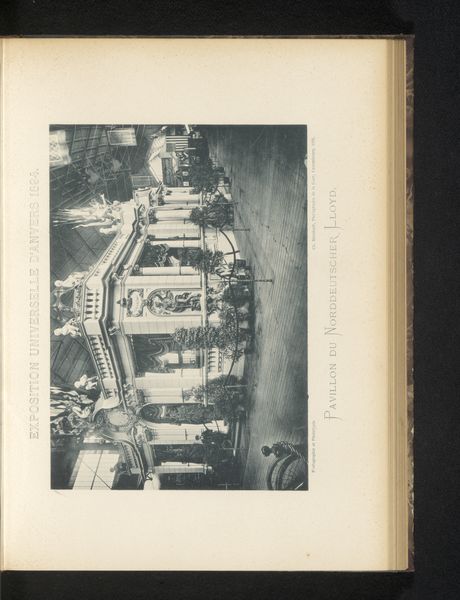

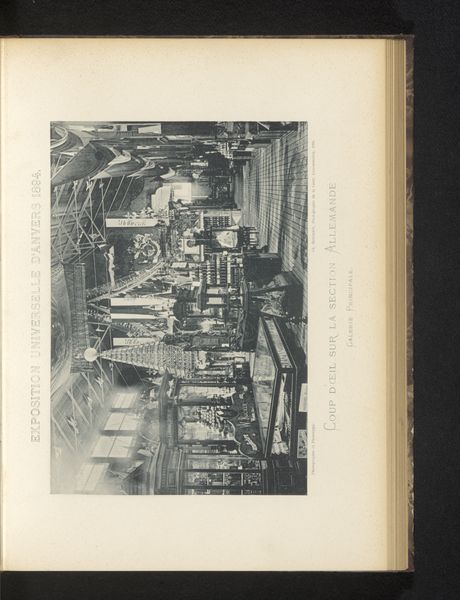

Curator: So, this albumen print from 1894 is titled "Gezicht op het Marokkaanse deel van de Wereldtentoonstelling van Antwerpen in 1894" by Charles Bernhoeft. Editor: My goodness, it's like a postcard from a dream. Or perhaps a wistful architectural rendering. There's a fragility to the image despite its grand subject matter. Curator: It does capture a sense of longing, doesn't it? Bernhoeft has documented the Moroccan pavilion at this World's Fair, offering us a glimpse into the elaborate constructions that represented other cultures. And yet the way the photo renders details… It seems almost ephemeral. Editor: Ephemeral is right. I can't help but consider the making of such a monumental stage set. What materials? Who were the builders? A structure intended to symbolize a culture reduced to commerce and tourism, all rendered in wood, plaster, perhaps the labor outsourced? Curator: It makes you consider the colonial gaze inherent in these expositions, and how they manufactured "otherness" for a Western audience. Though the artistry here, both in architecture and the printmaking, is undeniably captivating. The crispness of the image versus the delicate aging of the print… quite poignant. Editor: Yes, albumen prints, especially these large format ones, offer fantastic clarity. I wonder, did Bernhoeft develop on site, hauling a portable darkroom, or back in his Luxembourg studio? And what becomes of these structures after the fair closes its doors? Demolished? Sold? Reclaimed? Their labor lost to time and photographic processing, but here now a hundred plus years later. Curator: The photographic process feels like an echo chamber, doesn't it? Holding this trace of a trace. What did these structures really signify? To the builders, the visitors… Editor: It invites so many difficult questions, doesn't it? But it all circles back to the labour involved in dreaming these projects up, fabricating them, consuming and now documenting their likeness.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.