print, engraving

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 406 mm, width 517 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

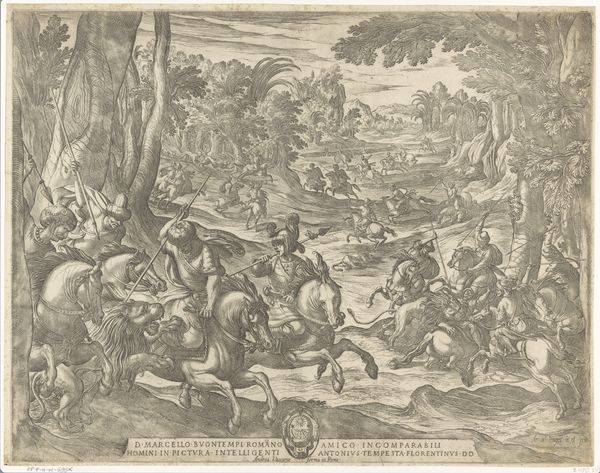

Curator: Here we see an engraving whose creation is attributed to Anonymous, made sometime between 1630 and 1702. The Rijksmuseum holds this depiction of "Pharaoh and his army drowning in the Red Sea." What is your initial reaction to this piece? Editor: My immediate impression is chaos and relentless energy. The scene is a churning mass of bodies and horses, all rendered with meticulous detail, characteristic of printmaking, while the inscription below feels very much connected to the making process of the art work itself, the means of its distribution... Curator: Indeed. Engravings like these, though unsigned in this case, functioned as accessible forms of storytelling in their time, often used to illustrate biblical narratives like this one. We see Pharaoh's army, weighed down by armor, succumbing to the very waters that parted for Moses and the Israelites, now safely on the opposite shore, depicted above to the left, bearing witness from atop the shores. Editor: The level of detail is astonishing. Every helmet, every crest of a wave, and the sheer density of figures create an almost overwhelming sense of doom. But consider the materiality; the deliberate lines etched into the plate, the labor involved in creating the printing block…it transforms a religious event into something grounded in the real world. It also speaks to the cultural value placed on these sorts of images; easily replicable through print, allowing this story and its inherent message to spread throughout different echelons of society. Curator: The visual symbolism is quite compelling as well. Notice how Moses, positioned high and dry, echoes a long lineage of representations of authority, even divinity. While the soldiers struggle and perish below, they are portrayed in very conventional terms, carrying symbols of royal power and warfare that are ultimately powerless against divine intervention. They become symbols of fallen glory. Editor: And it is interesting to think about consumption of these sorts of images too: consider the ways the rising merchant classes interacted with and possibly re-interpreted these images, that once were made to further solidify the place of traditional religion within culture. Curator: Ultimately, it reveals an event that resonates both the consequences of resistance and also the triumph of faith over oppression through symbolism, both sacred and temporal. Editor: Yes, thinking about all that labour really allows me to appreciate what the print signified. I hope that listeners enjoy it just as much too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.