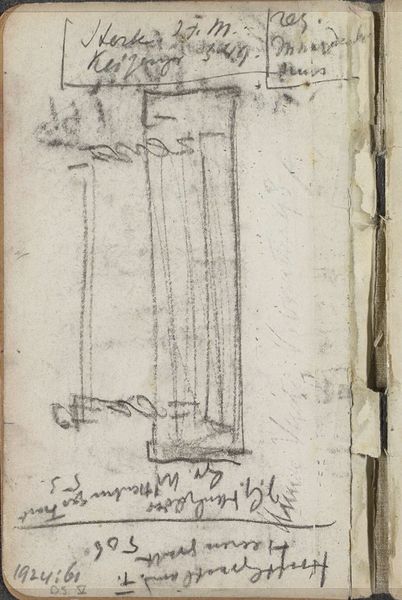

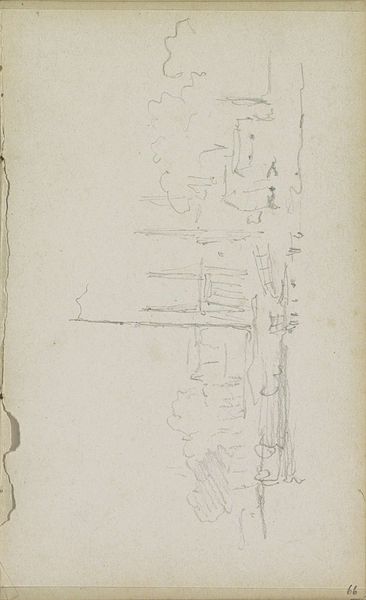

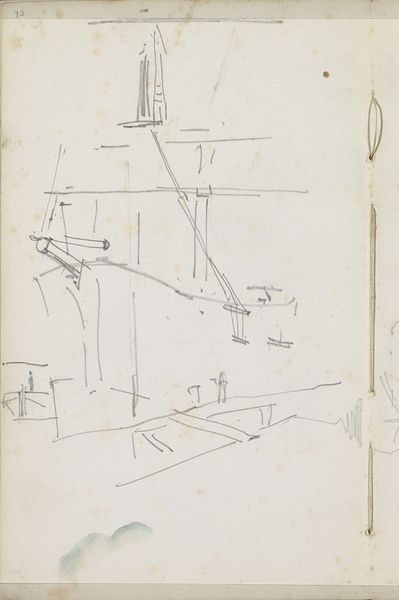

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

paper

#

form

#

coloured pencil

#

pencil

#

line

#

cityscape

#

realism

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have George Hendrik Breitner's "Architectuurstudies en een stadsgezicht," created between 1880 and 1882, a drawing rendered with pencil and colored pencil on paper, currently residing here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I'm struck by its immediacy, its raw quality. It feels less like a finished piece and more like a fleeting impression captured in a sketchbook. The line work is sparse, almost hesitant. Curator: It is quite informal. Given its status as a drawing, let's consider the paper itself. The subtle discoloration suggests age, of course, but it also speaks to its journey, how it might have been stored, handled, and the very conditions of its making. Consider the price of paper during this time! Not everyone had access to this, thus allowing him to draw. Editor: And looking at the composition, or lack thereof perhaps, reinforces that sense of the provisional. These aren't grand architectural pronouncements, but intimate sketches, almost studies of light and shadow. These studies almost feel utilitarian, tools of observation perhaps? Curator: Precisely! The cityscape hints at the urban landscape shaping Dutch society at that moment, the pressures and promises of modernization etched into the very fabric of these buildings, streets, and communities. What story did these sketches, produced and preserved by Breitner, mean? Were these to inspire later, grander works? It makes you think about the networks through which these images traveled at the time, shaping perspectives on city life. Editor: And it's fascinating to see those realist architectural studies in the context of the Dutch Golden Age style. There's this tension between capturing the gritty reality of urban development and the aesthetic traditions he's operating within. Breitner had to navigate the tension that realism can also mean depicting ugliness or inconvenient truths. Curator: Right. The very act of choosing to depict these everyday urban scenes, of elevating the commonplace, can be seen as a political act in its own way. Think about what he *wasn't* drawing. Who was being served by these new urban developments? Which members of society benefitted most from the changing material conditions? Editor: Yes, and in the end, it prompts reflection on how our perception of a time like the Dutch Golden Age is carefully built on art production and social context. What once seemed ordinary, a utilitarian collection of sketches of cityscapes in pencil on paper, are now charged with significance through their position in an esteemed collection, while prompting inquiries into materiality and context of social progress.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.