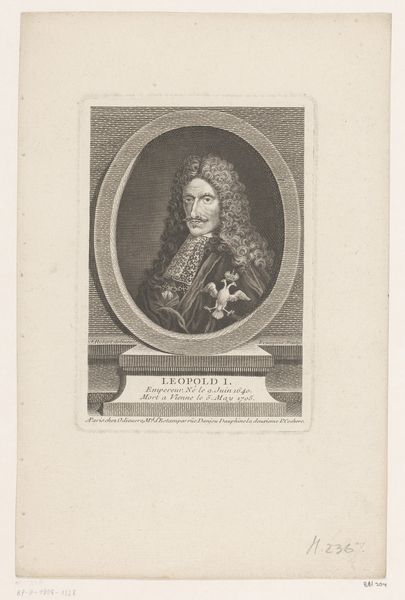

Dimensions: height 143 mm, width 79 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, “Portret van Philippe Néricault Destouches,” crafted between 1778 and 1787 by François Robert Ingouf, is a captivating example of late 18th-century portraiture. Editor: My first impression is how formal and almost detached it feels. The oval frame around the subject isolates him, making me consider the social status and the role of representation. Curator: Absolutely. Engravings like these served a very specific function. They were often reproduced to disseminate images of prominent figures. The material, the paper itself, and the repeatable process democratized image consumption while simultaneously reinforcing existing hierarchies. How were these prints produced and distributed, and what labor was involved? Editor: Precisely. Who was Philippe Néricault Destouches? A playwright! His image, carefully constructed, reflects the power structures of the era. The flamboyant wig, the cravat – markers of privilege against the backdrop of social inequalities prevalent in pre-revolutionary France. How did prints like this reinforce, or challenge the values of the elite? Curator: A point well taken. Looking at the technique, Ingouf skillfully utilizes hatching and cross-hatching to create depth and texture, particularly noticeable in the rendering of Destouches' wig. The detail is remarkable, showcasing the engraver's mastery. What was the social status of engravers like Ingouf, I wonder? Were they seen as artisans or artists? Editor: And think of the implied audience. Who could afford prints like this? And what message did it convey about the subject to see a version of him available on paper? Beyond aesthetics, how did the image function within 18th-century print culture and its role in constructing fame, celebrity, or reputation? It's about how these images were circulated and received in various social contexts, influencing opinions, preserving historical narratives and political projects. Curator: It prompts interesting questions about authorship too. Ingouf's name is clearly displayed alongside the sitter's, suggesting a collaboration. Considering it hangs in the Rijksmuseum now, removed from its original context, makes you ponder the evolution of artistic value. Editor: Exactly! We’ve moved beyond seeing it merely as a visual record of a notable figure. It is an artifact imbued with socio-political weight, its meanings constructed and reconstructed across time, forcing us to critically reflect on the production, reception and enduring legacies of portraiture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.