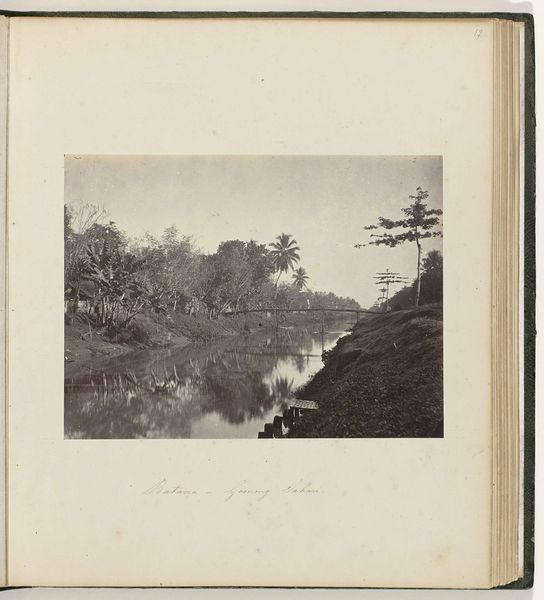

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

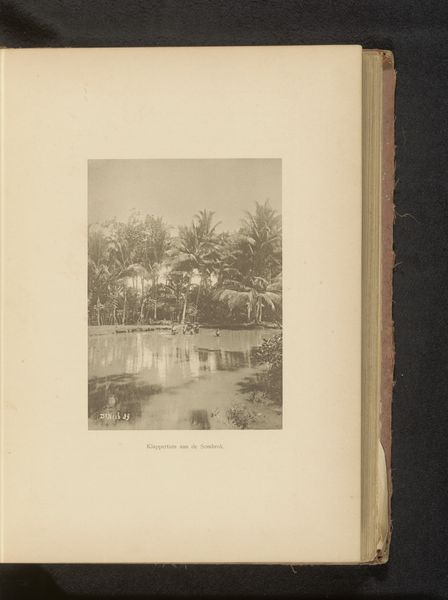

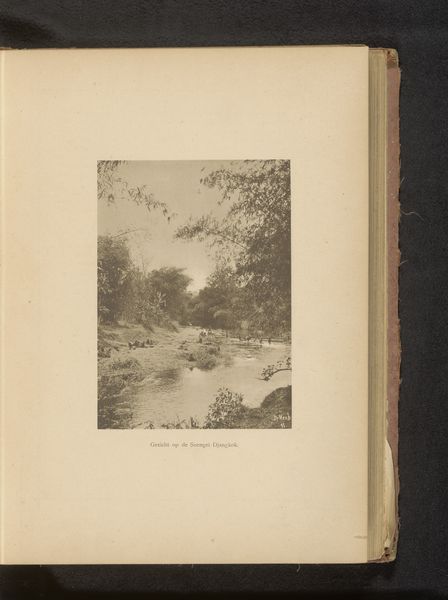

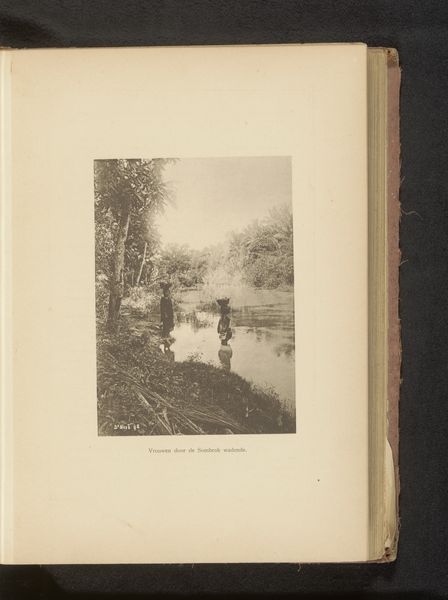

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 237 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Let’s take a look at this albumen print titled "Batavia - Parapattanbrug," created between 1863 and 1866 by Woodbury & Page. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: A subdued stillness washes over me. The hazy water reflecting the dense foliage gives a feeling of tropical weight and somber heat. Curator: Yes, and that hazy, dreamlike quality perhaps alludes to the exoticism of the East as perceived through a Western lens, a common theme in Orientalist art. Consider the symbolic weight of bridges as connectors between worlds, linking the colonizer to the colonized. Editor: That connection, literally the bridge's materiality, interests me. I wonder about the labour involved in its construction in that place at that time. And this photograph, a gelatin silver print. We often overlook the hands that mixed the chemicals, prepared the plates, and hauled the equipment through the heat to document this place. Curator: Absolutely. And the bridge itself, while seemingly a symbol of connection, might also signify control. It dictates the path, the flow. We are placed firmly on one side, the European side perhaps. Editor: Precisely, who had the resources to commission and circulate such imagery? Photography like this becomes part of a system, promoting colonial power and resource exploitation. How the exotic is transformed into a commodity. Curator: The albumen print's sepia tones contribute to a feeling of timelessness. It transforms the bridge into an ancient, enduring structure—even though it likely wasn’t. It reinforces the image of a mystical, unchanged Orient, inviting Western interpretation and intervention. Editor: I can’t escape thinking about the raw materials. Gelatin extracted from animal hides. Silver painstakingly mined and refined. Every element carrying a history of labor and environmental impact far removed from the romantic image on the print. Curator: It's a powerful reminder that images, even those that appear tranquil, are embedded in complex webs of power and production. Editor: Yes, revealing the unseen stories of labour and industry lurking beneath the picturesque surface.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.