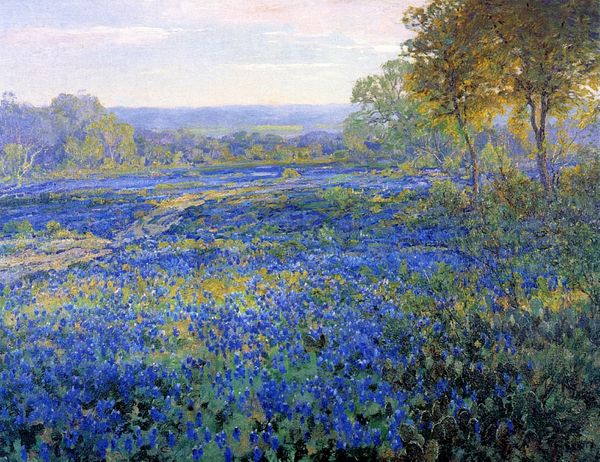

Copyright: Public domain

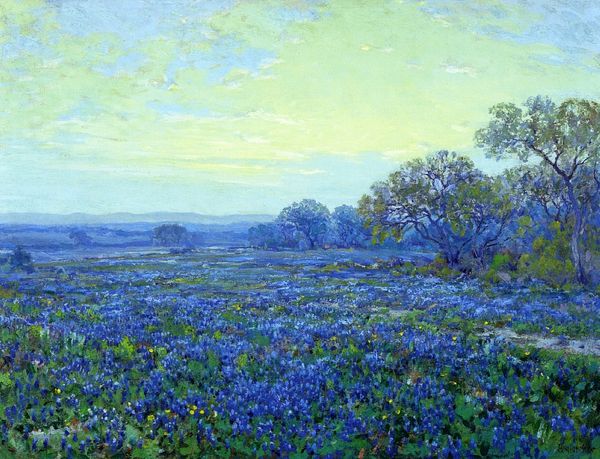

Editor: Here we have Robert Onderdonk’s "Bluebonnets, Late Afternoon, North of San Antonio" from 1920, an oil painting capturing a vast field of bluebonnets. It’s incredibly vibrant! What stands out to you in terms of its production? Curator: What interests me most is Onderdonk’s plein-air technique. Painting outdoors was more than just aesthetic preference. How did access to materials—portable easels, manufactured paints in tubes—democratize art making at the turn of the century? Think about who previously had the time and resources for creating landscape paintings. Editor: That’s interesting! So the impressionistic style, with its focus on capturing light and the moment, also depended on these material developments? Curator: Exactly! And the rise of middle-class leisure. Who is this painting for? Are these bluebonnets symbols of Texas pride, commodified through art? We need to consider how paintings like these become both representations of and investments in a particular regional identity. The materials literally *embody* this commercialization of place. Editor: So, is it fair to say that the “romantic” feel of the landscape belies some potentially more complicated social factors surrounding its creation and consumption? Curator: Absolutely. The mass production of art supplies made these scenes more accessible to produce, while simultaneously creating a demand and market for such picturesque images of the Southwest. Who benefited, and what was the impact of this visual rhetoric of a “romantic” and idealized landscape? Editor: I see! I never really thought about landscape painting in those terms before, focusing on materials, the mode of artistic labor, and who is buying. That's really fascinating. Curator: Considering those elements gives us a much fuller picture of this artwork’s value, in all senses of the word.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.