drawing

#

drawing

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

earth tone

#

light earthy tone

#

brown and beige

#

coffee painting

#

warm toned

#

warm-toned

#

watercolor

#

warm toned green

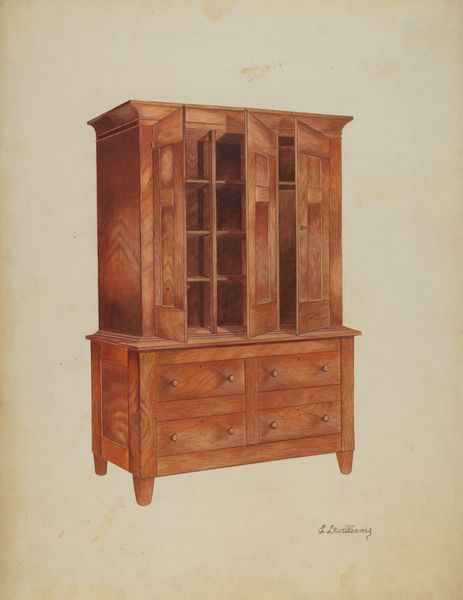

Dimensions: overall: 30.4 x 21.5 cm (11 15/16 x 8 7/16 in.) Original IAD Object: 36"high; 26 1/2"wide; 21"deep

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: We're now looking at "Chest of Drawers," a watercolor and drawing on paper completed in 1936 by Thomas J. Eliot. What strikes you first? Editor: Its imposing geometric facade, definitely. There's a calculated formality in the cabinet's severe symmetry that reminds me of De Stijl aesthetics or maybe Bauhaus design. Curator: That rigidity certainly speaks to the socio-political landscape of the 1930s, a time when efficiency and mass production were highly valued but also feeding into increased surveillance and control of private life. Did design become complicit? Is a chest merely a chest, or a container for secrets? Editor: Intriguing thought. Ignoring its societal position for a moment, look at the subtle gradation of color, how the light catches certain edges, softening its geometry in an optical game, playing with warm earth tones. Curator: I notice that you focus on the composition without the knowledge of Thomas Eliot himself. His story provides context for this period. It makes me wonder if he viewed the object in this manner. Editor: Maybe so, but these abstract shapes have their own grammar regardless. We could interpret them irrespective of Eliot’s stance during his time, understanding that his reality then influences design today. It still begs us to question form, regardless. Curator: Good point, there is something interesting in reclaiming history. Editor: I appreciate the depth and contrast achieved here, especially using such delicate watercolors. The precision is undeniable. Curator: Seeing through Eliot's lens, the drawing captures not only an object but the shifting societal norms of interwar Europe and anxieties tied to industrial modernity. How were class distinctions embodied by furniture? It all adds depth beyond visual structure. Editor: Agreed, the object does not need to be divorced from such contexts, or interpretations; but form gives context. I leave with even deeper questions around artistic intention in this period. Curator: It's fascinating how approaching this seemingly straightforward design stirs complex considerations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.