Æreskrans for den gudsfrygtige tjenestepige Susanne 1770 - 1814

0:00

0:00

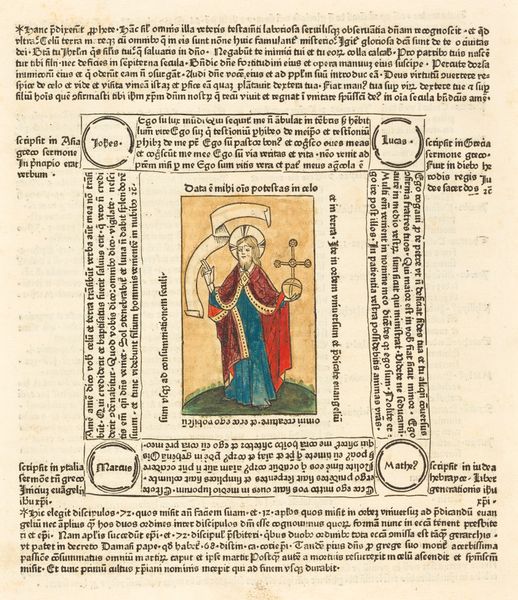

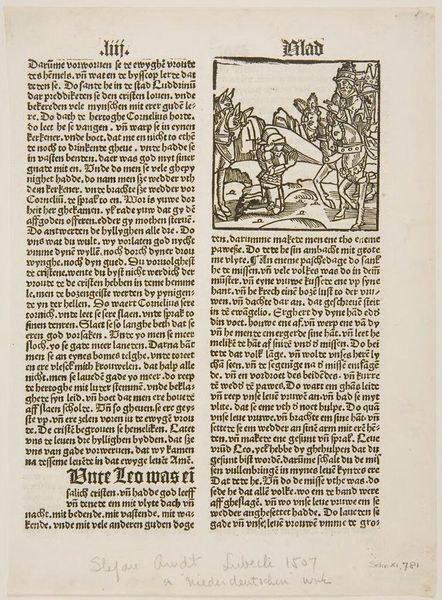

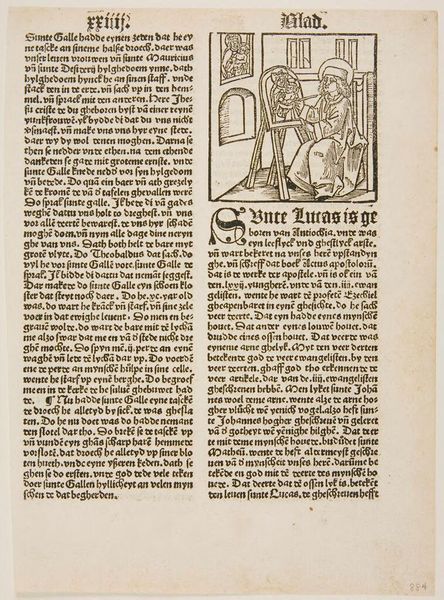

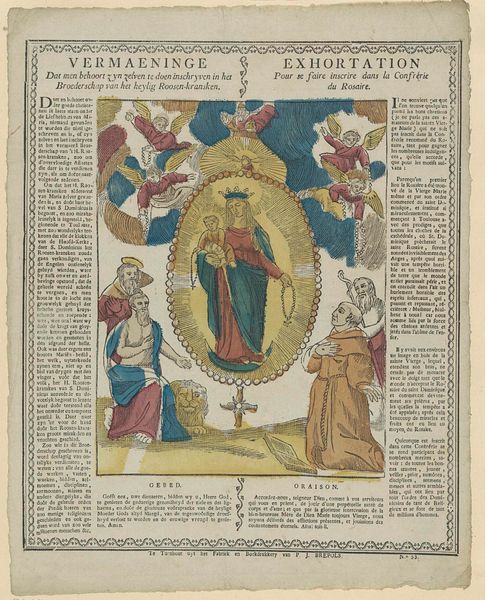

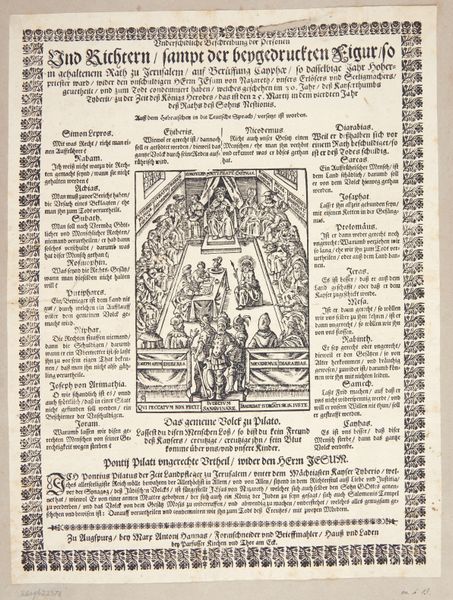

print, paper, ink, woodcut

#

medieval

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

folk-art

#

woodcut

Dimensions: 375 mm (height) x 272 mm (width) (bladmaal)

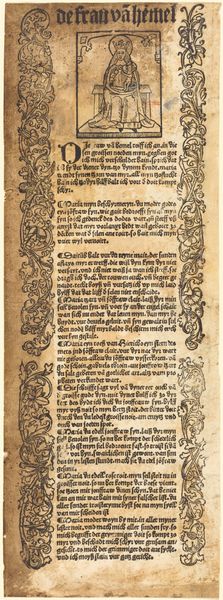

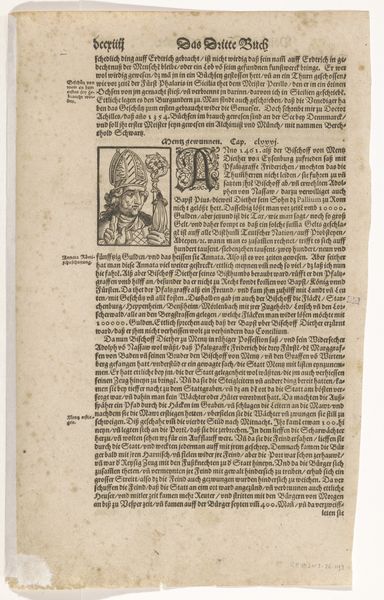

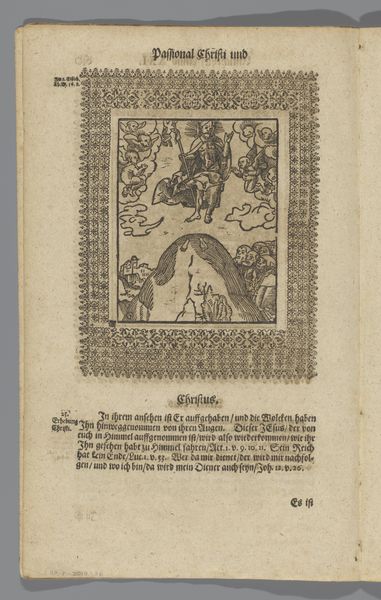

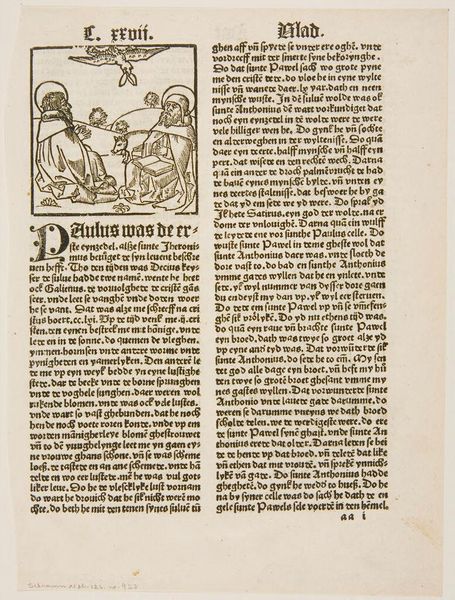

Curator: This intriguing print, titled “Æreskrans for den gudsfrygtige tjenestepige Susanne” – or “Wreath of Honor for the God-Fearing Maid Susanne” – was likely made sometime between 1770 and 1814 by an anonymous artist. It's an ink and paper print. Editor: My initial reaction is that it looks quite medieval and folksy. The colors are muted, almost faded, and there’s an almost comic strip quality to the figures with the dense text surrounding a central scene. It’s oddly charming and very much of its time. Curator: I agree, it evokes that sense of a bygone era. The use of woodcut as the printmaking technique suggests a particular method of production aimed at accessibility and potentially mass consumption by a wide, less affluent audience. These types of prints offered more common access. Editor: Absolutely. This artwork reflects several broader themes. It’s speaking directly to a female servant and a whole segment of marginalized working-class citizens. What kind of labor produced such works? What's the division of labor embedded here? Curator: Considering its materials, it wouldn't have been extremely expensive, ink and paper, widely available even then. This allowed the creator to offer religious iconography at an accessible price point. The visual design has strong ties to medieval folk-art, specifically the layout and framing with floral ornamentation feels reminiscent of devotional pieces of earlier centuries, so it does invite a sort of familiarity, despite not being tied to any specific medieval school of art. Editor: Yes, framing is vital here, as these ornamental elements draw you toward the core: identity, service, and religious faith. Even the print's texture, that uneven quality from the printing process, contributes to its charm and makes it a bit endearing. We can consider questions of female virtue in this period through looking at the ways it offers Susanna as the archetypal “good” maid and how women's domestic piety may or may not play into existing structures of oppression. Curator: It reminds me that things were intentionally accessible and replicable, which democratized the image but sometimes caused some creative freedoms to suffer. What are the limits? And at what cost? Editor: Exactly, and this is something for contemporary readers and viewers to consider. Perhaps what strikes us today as “charming” had stark and serious implications back then.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.