drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

cityscape

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

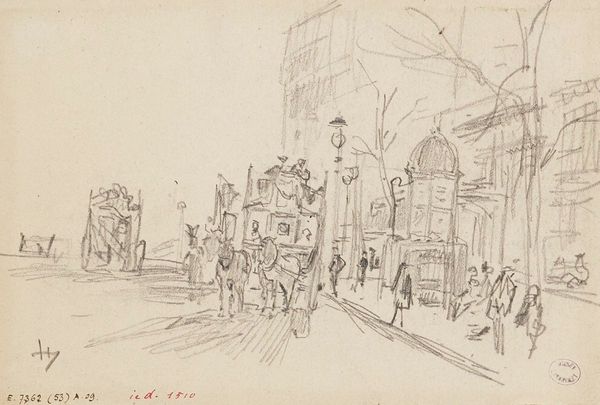

Curator: Looking at Fréderic Houbron’s "Rue de Paris," dating from between 1895 and 1905, rendered in pencil, I’m immediately struck by its ethereal quality. It’s like a half-remembered dream. Editor: Yes, it possesses an understated beauty, almost like glimpsing a past era. But how do you situate an image like this? I'm intrigued by what a pencil drawing, a medium often deemed preparatory, tells us about urban experience during that era. The rapid industrialization and modernization that transformed Paris… how do we see those forces at work here? Curator: It definitely captures a fleeting moment. Consider the urban experience through the flâneur, the stroller—a figure gaining prominence precisely during this period, as Paris reshaped itself. He, or perhaps in Houbron's vision, they – man and horse, foregrounded to the left – could embody the modern citizen, observing but not quite participating. Their subjectivity and interactions with urban space are essential here. Editor: That's a solid point. We often see idealized images of Paris, and Houbron’s choice of such an immediate medium hints at capturing something rawer, less polished. Is this, perhaps, a response against the grand narratives of progress, hinting at the social costs of such monumental changes? I also note the interesting tension between the precise, architectural details on the left building versus the blurrier elements towards the horizon. It makes me think about social fragmentation, which has come to impact urban planning during that era. Curator: Indeed! Think, too, about what drawing, rather than painting or photography, offers in representing the era. There’s a directness here that potentially aligns with feminist perspectives. Is this perspective on street life through a uniquely feminine lens? And the material reality – paper and pencil, widely accessible - what communities can engage with art through this medium, what stories it helps record? Editor: That consideration of inclusivity matters profoundly. I wonder, how did these works function in public space? What type of exhibition venues made such glimpses of the urban world available for interpretation by citizens? That accessibility shapes our interaction with urban representation, now as well as in the past. It gives us agency in creating counter-narratives against dominant ideals of modernization and aesthetic ideals. Curator: It really pulls us back to the fundamental question of whose history, whose vision of Paris, gets amplified and validated. I am keen to investigate more Houbron works. Editor: Absolutely. I think the conversation really shifted for me by thinking about art institutions and social values. Thank you.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.