drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

drawing

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed irregularly): 15 1/16 × 20 7/16 in. (38.2 × 51.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

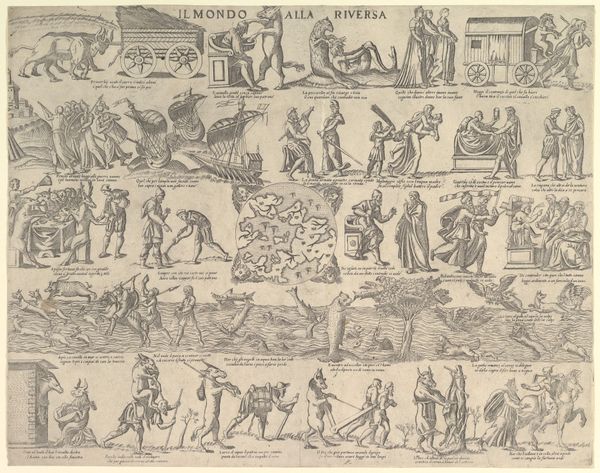

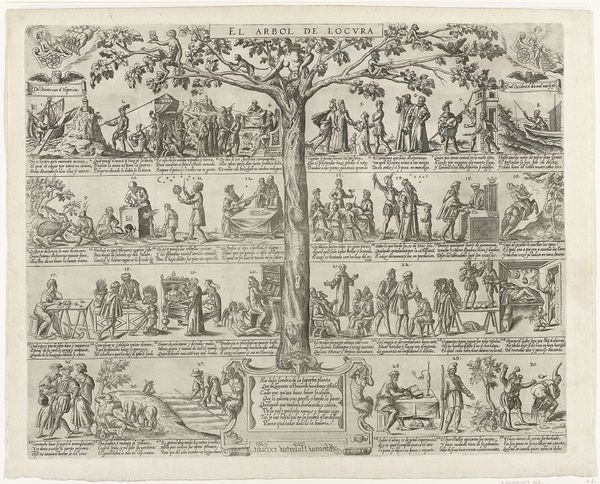

Curator: This print, "The Cage of Fools" or "La gabbia de' matti", created between 1557 and 1563, is attributed to Sebastiano di Re. It's currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. What strikes you first about this densely packed etching? Editor: Honestly, a sense of controlled chaos. It's teeming with figures, almost overflowing, and I immediately think about what systems are at play here. It makes me uncomfortable—like being in a crowd where everyone has their own agenda and no one is truly looking out for anyone else. Curator: I see what you mean. Di Re’s work certainly captures a moment of social anxiety during the Italian Renaissance. These vignettes are allegorical representations of human folly, each highlighting a specific vice or foolish endeavor. Think of it as a commentary on the political and social climate, particularly the anxieties around social mobility. Editor: And isn't that large globe right in the middle, with a man teetering on a ladder, indicative of the power structures that are in play? This man is striving, but he seems to be going nowhere fast—he's literally grasping for a world that feels out of reach, even dangerous, like a bubble about to burst. It calls to mind class disparities that dictate not just what one has access to, but, in some ways, what one *deserves.* Curator: Exactly! Note also the numerous inscriptions. They provide further context, offering moralizing captions that spell out the folly being depicted. For example, you have the figures squabbling over money, people succumbing to vanity, and others engaging in pointless intellectual debates. Editor: So it's like a catalog of societal ills, all meticulously documented through the lens of this period. The presence of Death itself in the lower-right corner makes this even more of a stinging indictment—as if to say that indulging in these follies isn’t just foolish, it's a path to destruction. Do you believe it served as a form of social critique meant for popular consumption, a visual sermon, so to speak? Curator: Absolutely. The print's accessibility would have allowed for a wider audience to engage with these critiques, influencing social discourse about appropriate behavior. It serves as a powerful reminder that art has long been used as a tool for societal reflection and critique. Editor: Ultimately, it is interesting to note that its critical lens offers insight into ways we can see art as both mirroring and shaping collective behavior and cultural norms—a conversation starter about who holds power, what we value, and who pays the ultimate price. Curator: Yes, its engagement with art in the public realm continues to stimulate vital and nuanced perspectives on these intricate social dynamics and the politics of imagery.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.