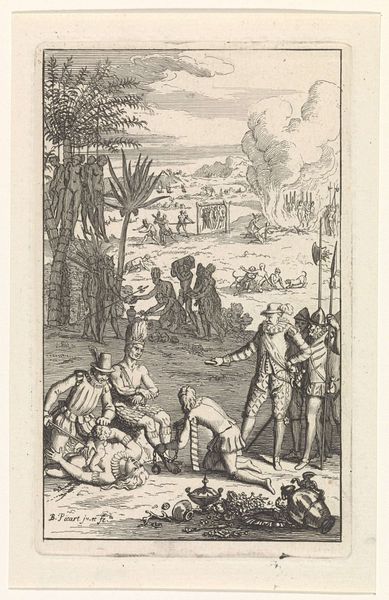

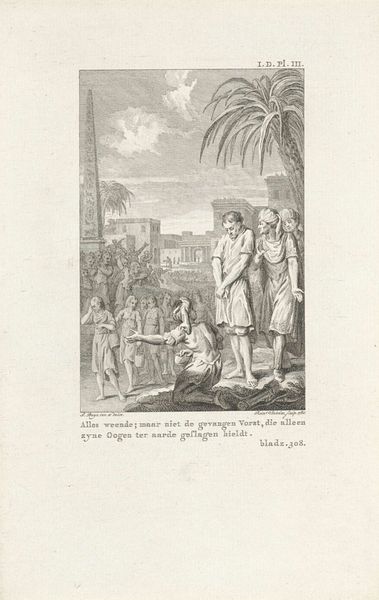

print, engraving

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

orientalism

#

line

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: width 137 mm, height 229 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

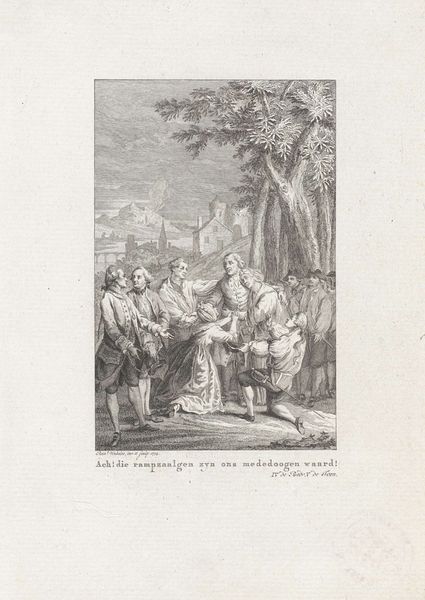

Curator: This print, titled "Bedelaars te China," which translates to "Beggars in China," was created between 1769 and 1805 by Jan Evert Grave. It's an engraving, so essentially a detailed line drawing captured on a metal plate. What strikes you immediately? Editor: There’s an undeniable theatricality. These figures are arranged in such a way, almost a stage tableau, that draws your eye through the layers of misery and resilience, all set against a somewhat idyllic backdrop. A weird juxtaposition, right? Curator: Absolutely, a key aspect of Orientalism. Grave presents us with his interpretation of Chinese beggars, but through a lens that highlights exoticism, rather than stark realism. Notice how their physical "deformities," as the Dutch text below emphasizes, become a spectacle. Editor: It is deeply unsettling, this staged poverty. The fellow balancing those objects on his head, for example. The gesture feels... performed. And look at the men with the exaggerated hairstyles—it feels almost mocking, rather than compassionate. Is it meant to depict authentic customs, or is it merely conjuring up images based on second-hand accounts? Curator: I think that's the tension at the heart of images like this. There is an attempt to document, to present the unfamiliar to a European audience. But inevitably, it is filtered through the artist's own cultural biases, what they think "China" is. The symbolism then serves a pre-conceived narrative. It perpetuates stereotypes even while seemingly trying to offer a glimpse into a different world. Editor: I keep coming back to the tree, though. That lone palm – so vividly drawn, so deliberately placed. In Western art, the palm often signified the Orient and everything perceived as luxurious, languid, and other. Curator: Yes, the palm is doing heavy lifting as a symbol, definitely anchoring the scene within a colonial imagination. For audiences then, and, perhaps, even now, it provides the visual cues that tell the viewer how to feel: distance, intrigue, and maybe a slight condescension. It prompts a critical question about representation and our responsibility in confronting such problematic imagery. Editor: Looking closer, it is unsettling. One hopes we might view such artworks not just as historical records but as vital reminders to constantly re-evaluate our perception, lest history repeat itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.