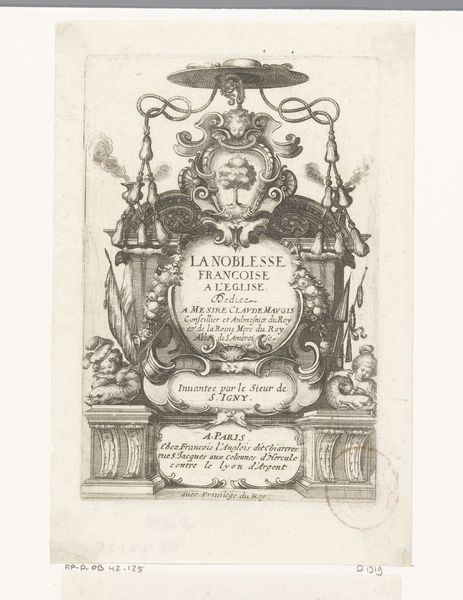

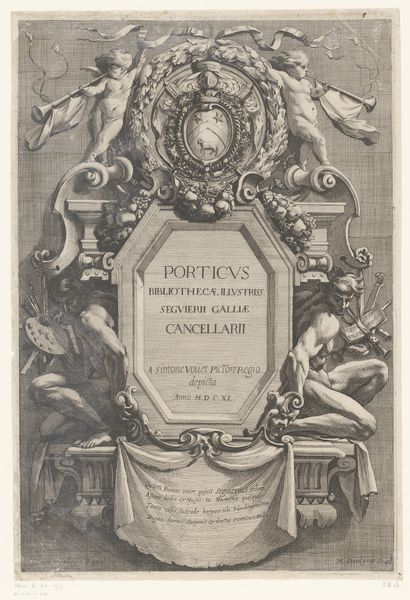

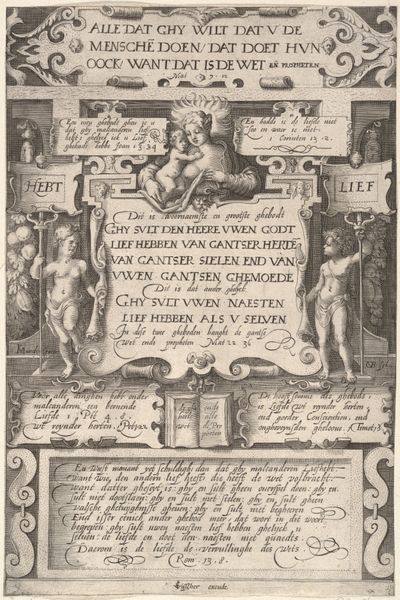

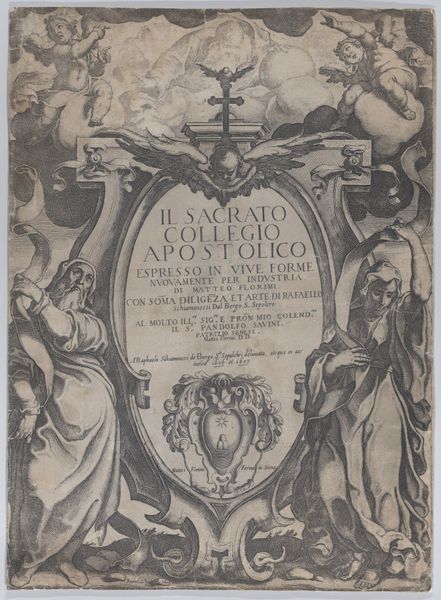

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

calligraphy

Dimensions: height 260 mm, width 194 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving by Richard van Orley, created sometime between 1695 and 1705, titled "Aminta offert zichzelf in plaats van Lucrina." My initial impression is one of intricate ornamentation surrounding text. What catches your eye? Editor: The abundance of symbolic ornamentation. Just look at those cherubs and elaborate architectural motifs flanking the heavy, gothic script; it almost feels overwhelming. Are we meant to see the written text or the visual cues as primary here? Curator: Good question. Van Orley was working within the Baroque tradition, so excess and opulence were certainly prized. The technique employed – engraving – speaks to a labor-intensive process of production. How the matrix for printmaking was handled – etched with acid, engraved with burins – suggests a dedication to precise rendering but it might as well have taken longer than necessary to get this quality. It certainly tells us that making art like this was a status display. Editor: Yes, the level of detail is remarkable. Consider those putti and lion heads embellishing the Corinthian columns—and then juxtapose that with the crisp text in the center, all of it intended to lend a sense of imperial authority through the use of familiar imagery of Roman rulers. And who were Aminta and Lucrina that prompted this work's existence? What does the tale of self sacrifice here evoke, historically? Curator: Historical context is important. The prints were relatively affordable art commodities for an upcoming burgeois class, especially since these subjects allowed their commissioners or buyers a window into understanding better the culture of aristocrats, of monarchs and even empires, whether recent ones or past ones. Looking at something like the weave or paper would reveal production techniques, including evidence that sheds light into the history of the trades, of work guilds, or the circulation of engravings, to help trace paths to consumer or buyer of these. Editor: I suppose I was wrong. It is difficult not to want to understand what Van Orley tries to signal; and how historical awareness is important for contemporary or current understanding of who we were, are, and what do these symbols communicate with the right socio-historical analysis, whether of our class structure, consumption and manufacture, these elements will make the symbology stand more vividly to us. Curator: Absolutely, engaging with historical awareness helps better grasp Van Orley's intent of historical narrative embedded in the work itself. I learned much today; now back to analyzing art, craft, commerce, history... and meaning. Editor: Likewise. Examining it together has brought me insight and pleasure too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.