Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

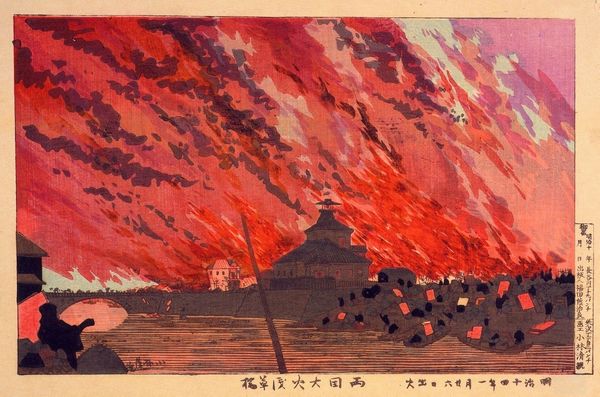

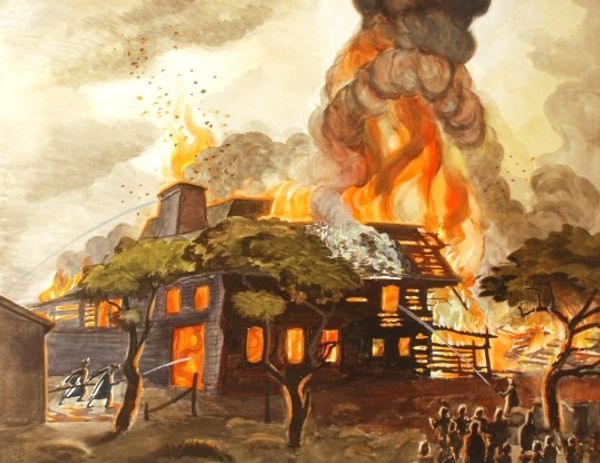

Curator: Looking at this watercolor by Kobayashi Kiyochika, titled "Great Fire at Ryōgoku Sketched from Hamachō, January 26, 1881," one immediately senses a dramatic atmosphere. What's your first impression? Editor: There's a definite sense of urgency; the smoky sky is striking and it’s full of raw power and destruction. The contrast of the fleeing figures on the lower bank and the looming flames speaks to the precariousness of everyday life for many in that period. Curator: Indeed. Kiyochika was known as "the last ukiyo-e master" and also "the artist of light." Ukiyo-e prints were traditionally woodblock, produced through collaborative labor, but Kiyochika worked in new, singular ways and also experimented with Western painting techniques, as evident here with his masterful capturing of light and shadow in watercolor. Editor: The scene captures a specific historical event, but it transcends documentation. The fire symbolizes not just destruction, but societal vulnerability and the often-unequal impact of disasters based on location and class. Where were such conflagrations situated within the rapidly changing urban fabric of Meiji-era Tokyo? Curator: The materials employed here are particularly telling. The paper itself appears aged, imparting a sense of time and history even before the scene unfolds. Watercolor lends itself well to capturing transient effects like smoke and flames; notice the paper's texture too; it adds depth and movement. This wasn’t mere record keeping, it was artmaking tied to social issues. Editor: I agree, looking closely, the urgency of the running figures along the waterside. Their postures show their immediate reactions, perhaps driven by the loss of property and potential homelessness from the raging flames across the river. Was Kiyochika examining social support structures for dealing with loss and destruction? Curator: Absolutely. Kiyochika came from a Samurai family that fell on hard times. Perhaps, in this way, he offers insight on shifts in social and economic status, focusing on human experiences rather than on abstract principles of art history or criticism. The method of production is important too. How many similar images did he disseminate to create broad access and, indeed, awareness? Editor: Exactly. This work prompts us to consider the role of art not just as a beautiful object but also as a commentary on urban inequality, class vulnerability, and social turmoil. It invites critical thinking and social action. Curator: Right, and examining Kiyochika’s innovative painting style helps us reconsider divisions of labor and making, broadening perspectives in art history. Editor: Indeed. There is no objective view, only vantage. Let's give listeners time to ponder and reflect further.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.