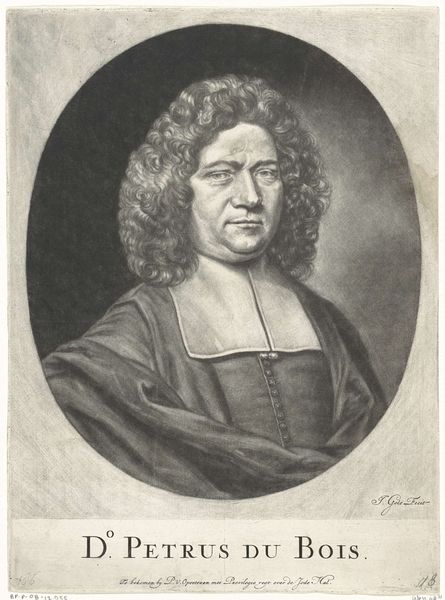

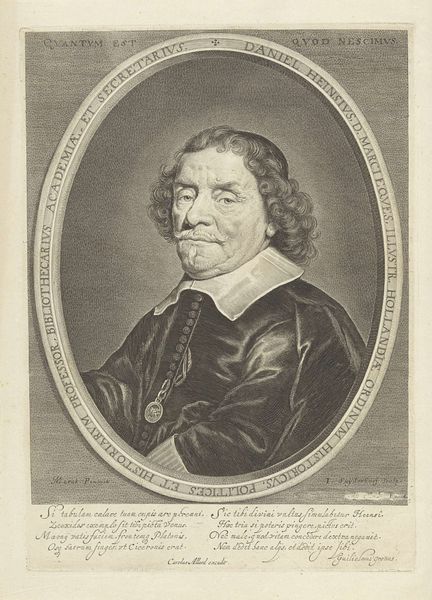

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 283 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I see Petrus Aeneae's "Portret van Jacob Rhenferd," an engraving dated between 1680 and 1700. It strikes me as rather formal, almost austere, even with the baroque flourishes. The detail in the clothing and hair is amazing. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It’s a beautifully rendered print. I am struck by the skill it must have taken to create such fine lines. Considering it’s a print, how does that influence its context as an artwork in that period? Curator: Exactly! Let's consider the materiality of this engraving. Engravings are inherently about reproduction, making images accessible to a broader audience. Who could afford or even see this man otherwise? And what materials were available to the artist? The paper, the ink, the tools. They all speak to a specific moment in technological development and access to resources. We can't ignore the labour involved, too. How many prints could Aeneae make, and who would have distributed them? It wasn't simply the creation of *high art* we can witness but instead a skilled labour. Does this change your perception of the artwork? Editor: That’s fascinating. So it's less about individual genius and more about access, labour and distribution of a potentially reproducible object? I'd never considered the implications of that. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on the materials and production, we can see how "art" is enmeshed within broader economic and social systems, challenging our modern-day notions about artistic genius and unique art objects. Editor: That makes me appreciate the print even more now. I’m going to start seeing all art differently! Curator: Me too. Let’s find out how printing enabled the dissemination of knowledge during the 17th century!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.