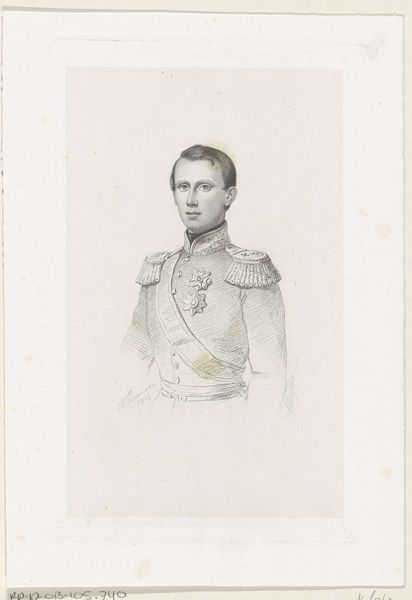

drawing, engraving

#

portrait

#

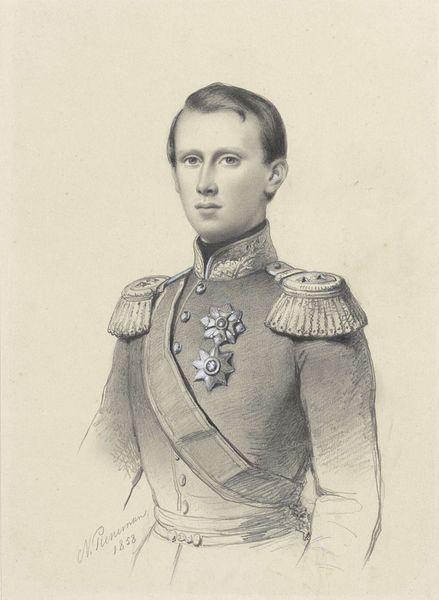

pencil drawn

#

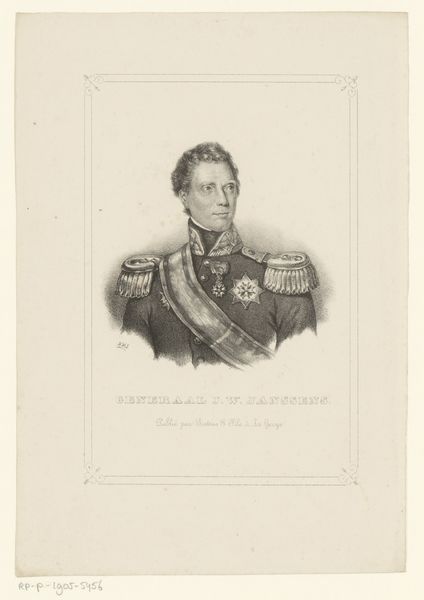

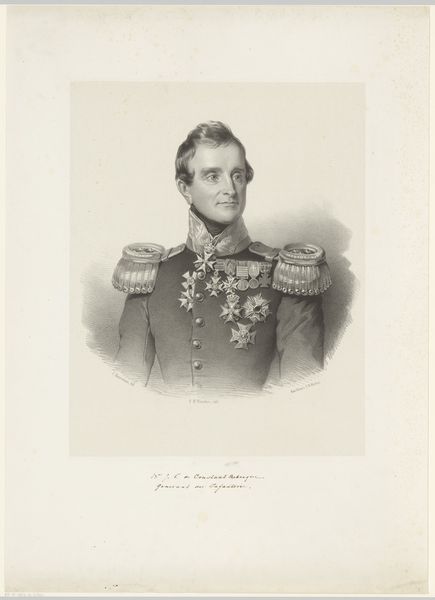

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

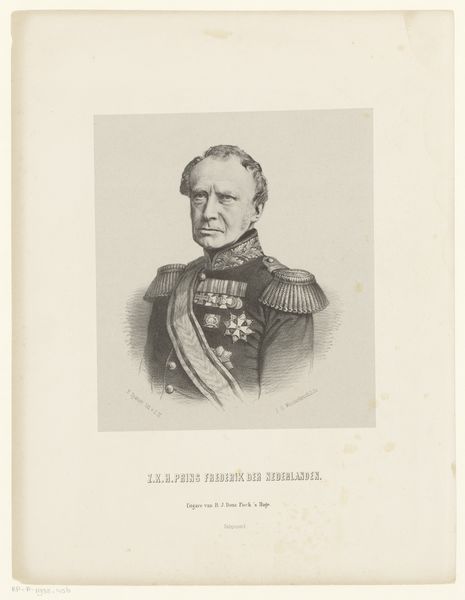

Dimensions: height 545 mm, width 362 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Up next we have "Portret van Willem, prins der Nederlanden," or "Portrait of William, Prince of the Netherlands," created between 1850 and 1882. The medium appears to be engraving. Editor: My immediate reaction is one of austerity. It feels…reserved, doesn’t it? The subject looks almost trapped by the formality of it all. Curator: Absolutely. It speaks to the constructed image of monarchy in the 19th century. Portraits such as this were crucial tools in shaping public perception and legitimizing power. It’s a carefully managed performance of status and authority. Editor: Precisely. Consider the visual cues: the elaborate uniform, the stern expression. How do those contribute to the construction of an idealized, almost unattainable, image of leadership? This portrait exists not as a likeness, but as an instrument. Curator: Very true. And the distribution of these engraved portraits – think of newspapers, public buildings, private collections – allowed this carefully crafted image to permeate society. This visual saturation reinforced the social order. Editor: And think about who is left out of this "order". Consider how visual representation reinforces existing power structures while simultaneously marginalizing other communities and experiences. Curator: That's a vital point. These representations served as potent symbols, actively excluding many other individuals and communities. We often overlook how consistently particular individuals have historically been amplified, while others were obscured from the public eye. Editor: Which makes analyzing the visual language all the more critical. Whose stories are considered worthy of representation? Whose narratives are erased in service to a singular, often dominant, worldview? The art world—or at least the version represented here—needs reckoning, still. Curator: Well put. It reminds us of the continuing need for art institutions to critically examine the historical power dynamics embedded within our collections and narratives. It’s not about erasing history, but about ensuring we are presenting a more complete and inclusive picture. Editor: I agree wholeheartedly. This work then becomes a touchstone for understanding both its historical context and our current responsibility to interrogate those inherited legacies.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.