Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

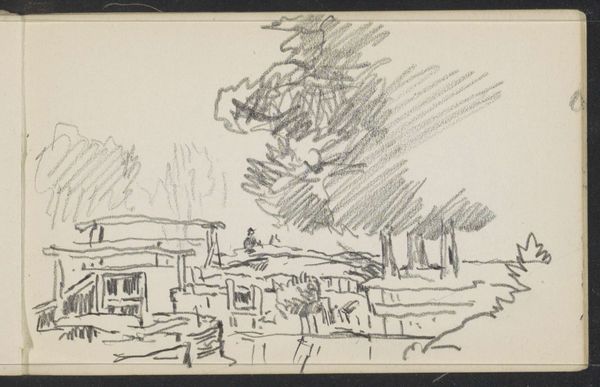

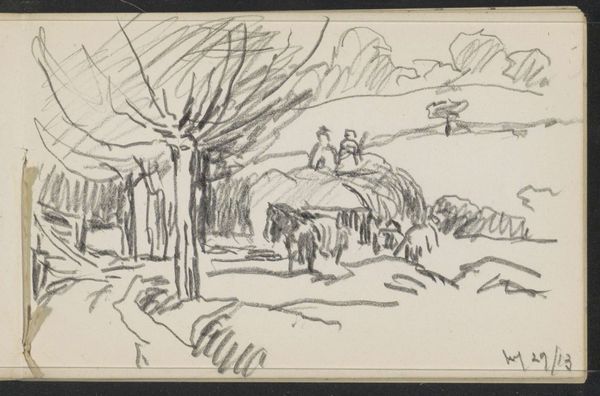

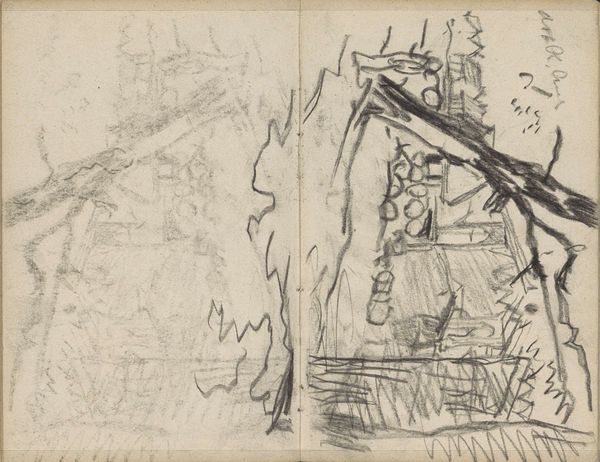

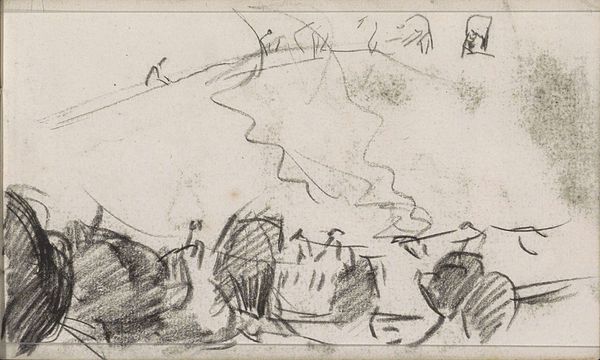

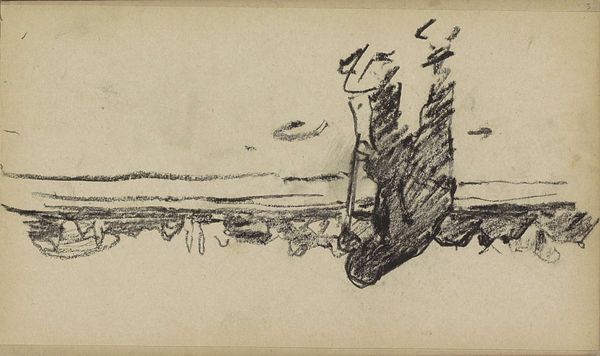

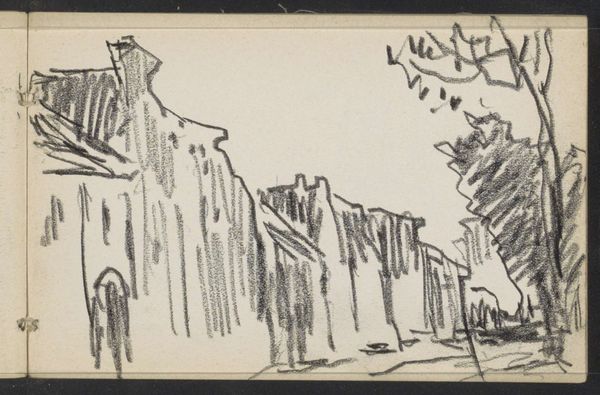

Curator: Today we’re looking at Alexander Shilling's graphite drawing, "Schellemolen aan de Damse Vaart," created in 1923. It seems to capture a slice of rural life with remarkable spontaneity. Editor: My first thought is how evocative it is, even with so few lines. There’s a sense of stillness, almost melancholy, perhaps enhanced by the monochrome palette. The looming windmill suggests a sort of slow, grinding… well, inevitable process. Curator: Indeed. Considering Shilling's broader interest in depicting working-class communities and rural landscapes, one can contextualize this piece within a broader historical narrative of early 20th-century artistic explorations into socio-economic life in the Belgian countryside, where landscapes were often intertwined with labor and production. How does this raw materiality reflect the socio-political conditions of its creation? Editor: It certainly highlights the agrarian world. The stark lines emphasize the physicality of the scene: the windmill, the waterway, the trees—everything feels immediate and tangible. This suggests a grounding in material reality, focusing on how landscapes directly reflect the communities tied to the work they afford. You can see a strong affinity with plain-air drawing practice. The rough graphite seems to emulate the textures it captures. Curator: Right. There is also a fascinating interweaving of the traditional, like the windmill which would have served crucial agricultural purposes, with what appears to be a conscious choice for representing it without romanticising rurality. This challenges traditional artistic approaches of his time that tended to idealise the natural landscape while erasing evidence of working communities and the processes inherent in their livelihoods. Editor: Absolutely, it shows that there are people and labor that built the landscape around us, not the other way around. I think it encourages an appreciation of what labor generates out of raw natural matter, whether through its cultivation in landscapes, its extraction of precious goods or in this particular context, milling of grain into flour. Curator: So, both artistically and politically, the act of depicting this landscape with these elements suggests something broader than merely aesthetics—an active engagement with ongoing questions about the relationship between rural industry, working-class lives, and an changing social fabric in 1920's Flanders. Editor: It gives pause, doesn't it? Seeing it through that lens makes the scene all the more powerful. The labor itself of production. Curator: Precisely. It is more than just a drawing; it's a statement, both visual and socio-political. Editor: I appreciate that reframing. I’m left considering the silent grind that the landscape suggests: work, material, context, and our perceptions about them.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.