drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

perspective

#

paper

#

form

#

geometric

#

pencil

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

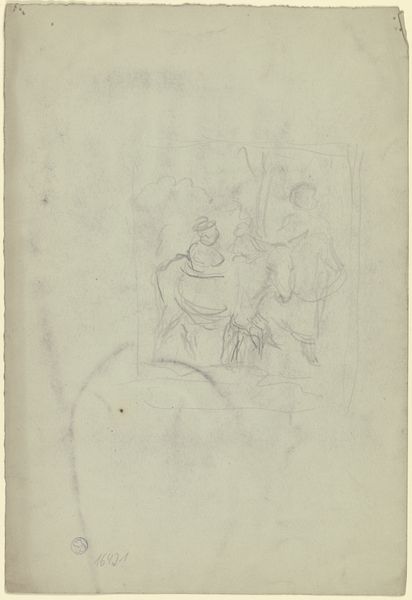

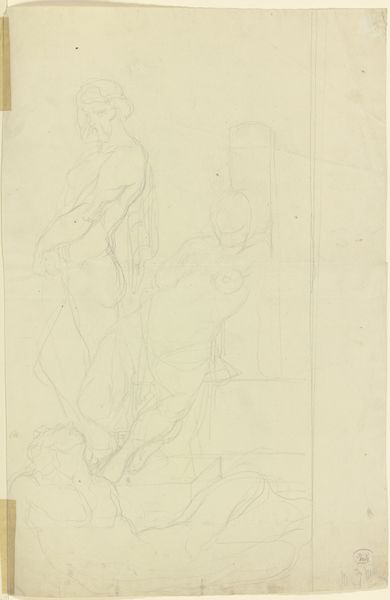

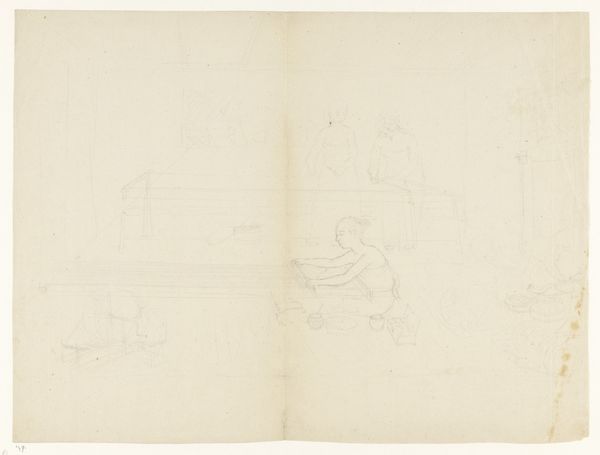

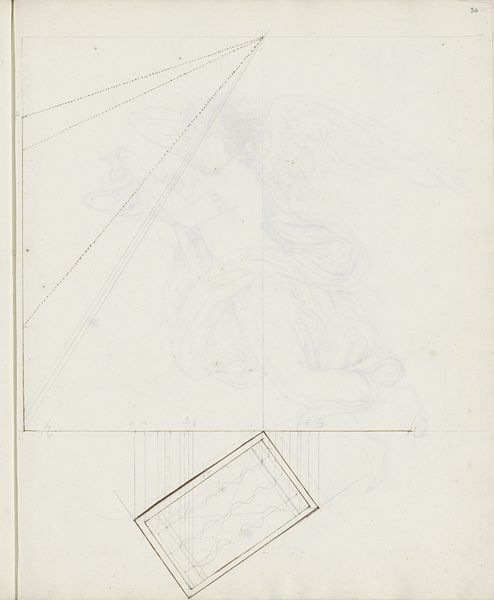

Curator: This is Catharina Kemper's "Perspective Exercise with a Cube," dating back to 1813. It’s a pencil drawing on paper. My first impression is its quiet precision; it’s very faint, very deliberate. Editor: The sparseness is compelling. It's a whisper of an idea. One can appreciate the artist working on representing 3-dimensionality, the exercise she's undertaking but I can’t help but read into the idea of creating an exercise in early nineteenth-century Netherlands. Were such teachings accessible to all genders and classes? Curator: It's important to remember that Kemper was working within a neoclassical tradition, which highly valued rational thought and order, which can seem contrary to a more revolutionary period unfolding throughout the west at that moment. Think of it within the context of artistic training, a way to understand and depict the world through precise geometry, as a way to create artwork in other mediums too, in later phases of education, Editor: Right. Perspective became almost scientific. The cube becomes an emblem, doesn’t it? It symbolizes both structure and, because it exists only on paper, possibility. So what are we to make of the rest of the image? Curator: Here, she adds other visual material to illustrate that representation: faintly visible on the left, beneath and behind the cube, is a sketch of a mythological figure, a scene from classical history perhaps. One must develop the skill to be able to portray these figures using newly accepted and explored systems. Editor: That adds a compelling layer. This wasn’t merely an academic exercise; it's almost as though we’re catching a glimpse into Kemper’s broader creative aspirations, filtered through the lens of what was deemed academically essential to learn as an artist. But as much as neoclassical ideals prized universality, who has access to universality is of primary consideration for the reception of this piece. Curator: The limitations on education for women definitely shape the viewing experience, and her desire to study the great figures from the past. Art like this asks us to look closer, both at the drawing itself and at the socio-political contexts surrounding it. Editor: Yes, thinking about art as embedded within its era enriches our interpretation and broadens art historical canons.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.