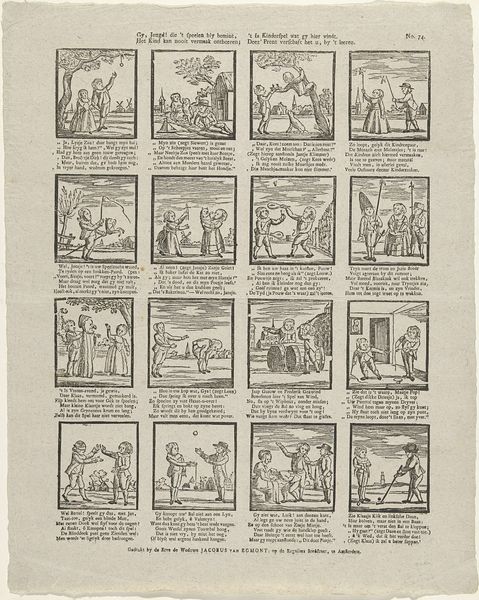

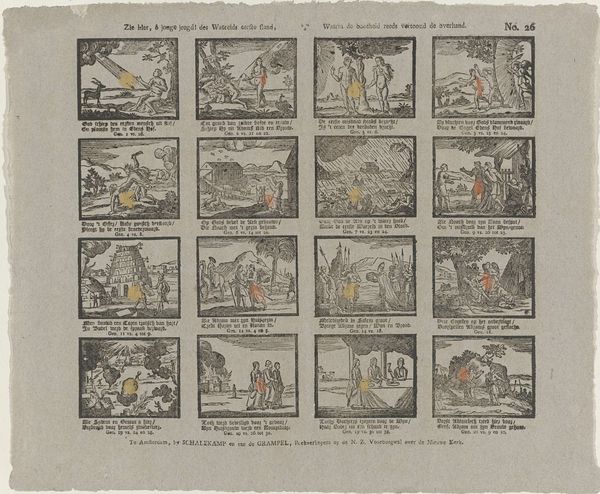

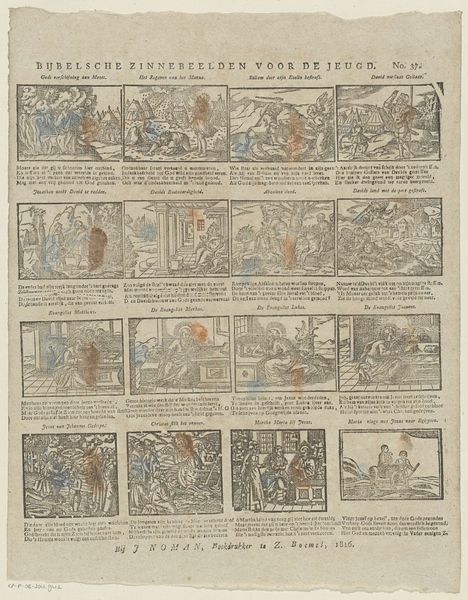

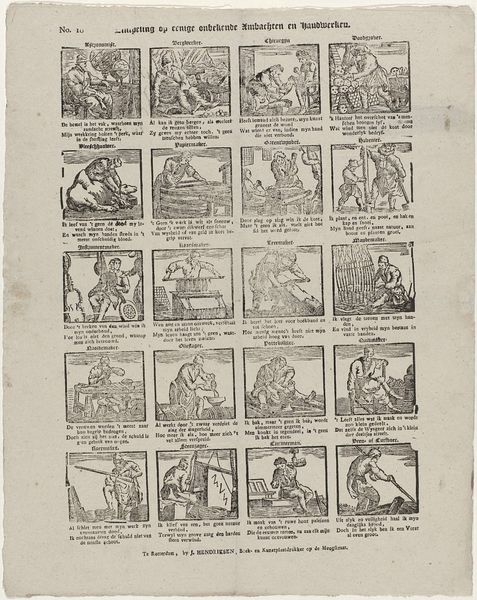

Let, schrandre Jeugd! op 't nut dat u deez' prenttafreelen / Van veel historiën des bybels mededeelen; / Beschouw hier Josephs lot, verhoogd na veel gekwel, / Als ook wat Moses deed, door God, voor Israël 1715 - 1813

0:00

0:00

jrobyn

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

comic strip sketch

#

narrative-art

# print

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 423 mm, width 329 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

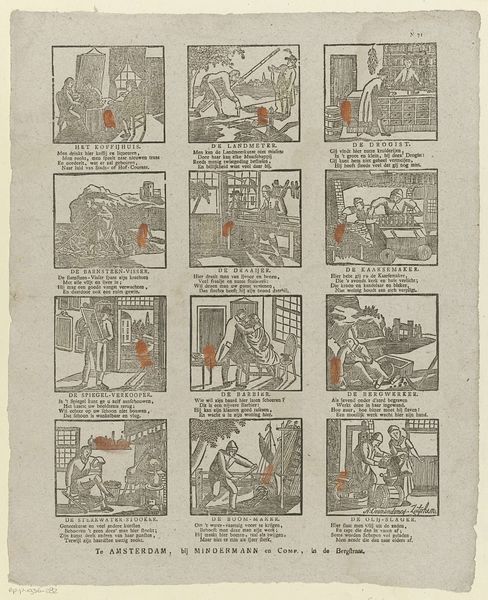

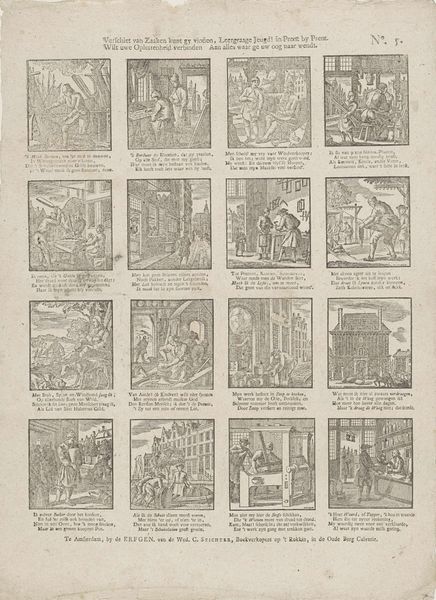

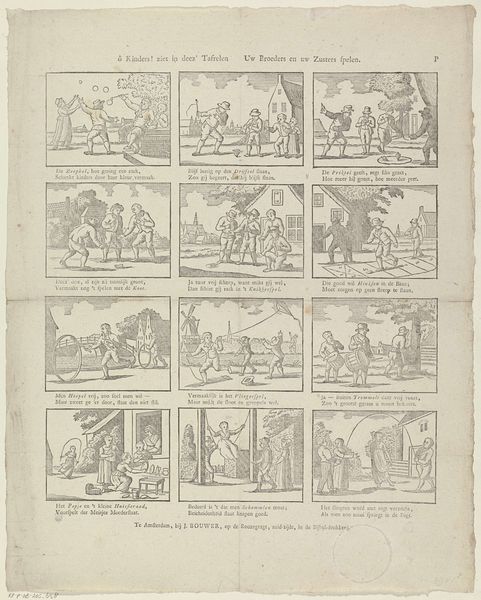

Editor: Here we have “Let, schrandre Jeugd! op 't nut dat u deez' prenttafreelen,” an engraving by J. Robyn, sometime between 1715 and 1813. It presents as a comic strip depicting Biblical stories, primarily focused on Joseph and Moses. The individual scenes are quite small and detailed; I wonder about the intention behind presenting it in this format. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see an interesting tension between high art and the burgeoning popular print market. Engravings like these democratized imagery. The materials – the metal plate, the paper, the ink – and the printing process itself, meant that religious narratives, typically reserved for elite consumption, became accessible to a wider audience. We need to consider the economics of printmaking at this time: Who commissioned this work, who was the intended audience, and how was it distributed? Was it part of a larger publication? Editor: So you’re saying the value isn't necessarily in its artistic merit, but more in its role as a tool for mass communication? Curator: Precisely. The means of production and circulation are key here. Robyn's individual artistic vision takes a backseat to the broader social and economic forces at play. Look at the standardization, the uniformity in each panel – these are products of labor, part of a commercial exchange. Editor: That's a fascinating way to look at it. I tend to focus on the narrative aspect, but understanding its place in printmaking changes my perspective. Curator: Considering the material conditions behind artwork enhances our appreciation and reminds us that art is always a product of its time, deeply embedded within systems of labor and value.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.