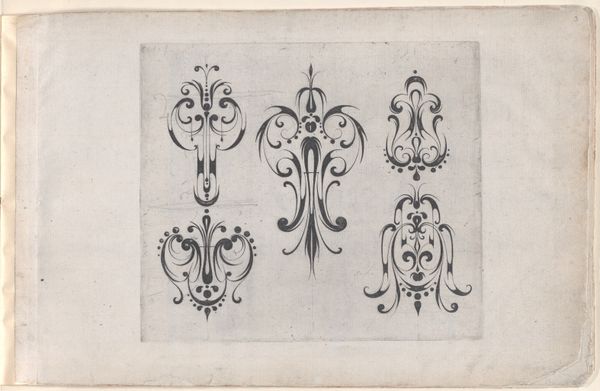

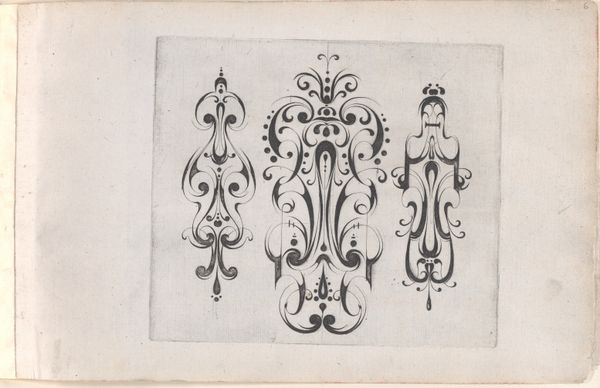

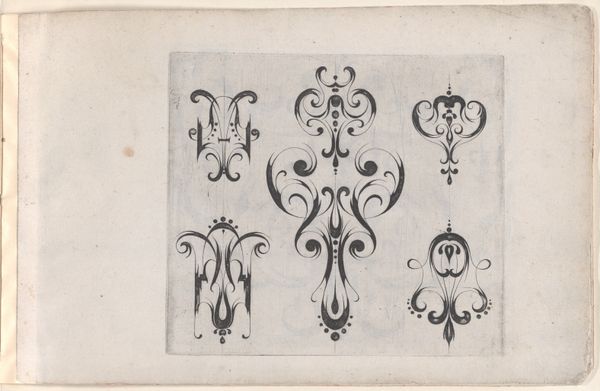

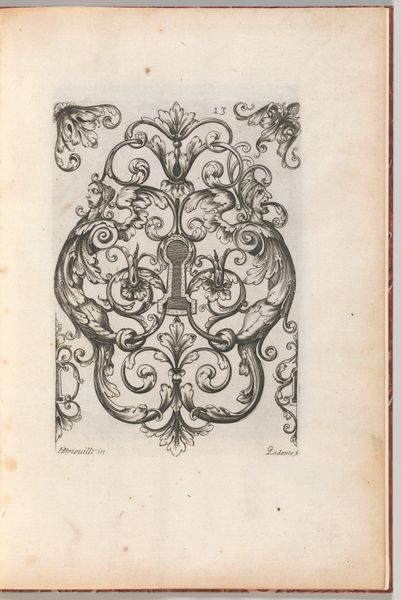

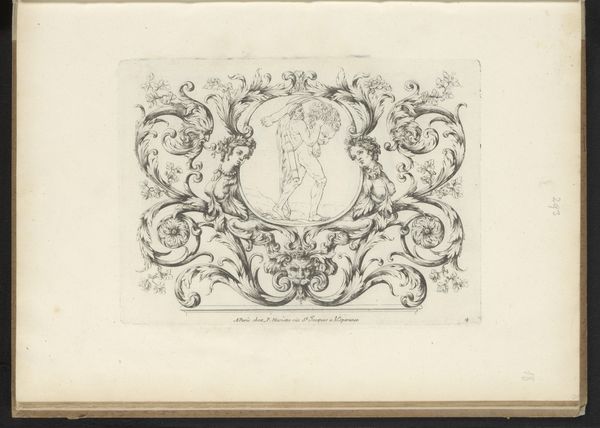

Plate from the Print Series 'Grateske voer golt smeden Schrijnwerkers Ende andere des nodich hebbende' 1605 - 1615

0:00

0:00

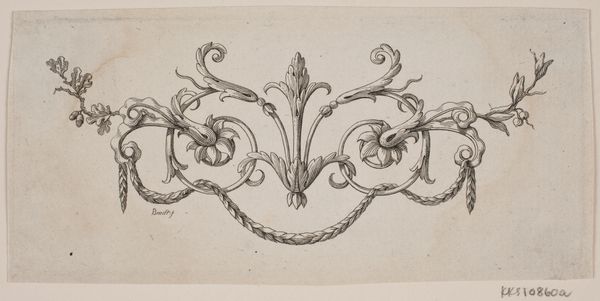

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

ink

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: 7 3/4 × 11 7/16 × 1/8 in. (19.7 × 29 × 0.3 cm) Plate: 5 3/8 × 6 1/8 in. (13.7 × 15.6 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This engraving from around 1605, titled "Plate from the Print Series 'Grateske voer golt smeden Schrijnwerkers Ende andere des nodich hebbende'", by Meinert Gelijs, features these intricate, symmetrical designs. It feels almost like blueprints, but for something much more decorative than functional. What do you make of its role in society at the time? Curator: It’s interesting you say blueprints. These kinds of engravings circulated as pattern books, part of a growing market in designs readily available for artisans to adapt. Consider how these prints democratized access to fashionable ornament. This wasn't necessarily "high art" meant for display, but a tool impacting the visual landscape. Think about the guilds, workshops…who controlled imagery and how did printed patterns disrupt established hierarchies? Editor: So it's like an early form of mass production for artistic ideas? Did this standardization limit creativity, or did it open new possibilities? Curator: That's the key question! Some might argue it led to a homogenization of style, dictated by what could be easily reproduced and sold. However, others, and I tend to agree, see these prints as catalysts. They facilitated the spread of new motifs and encouraged innovation as artisans reinterpreted and combined designs. Think about the rise of the Baroque; how much of its exuberance was fueled by access to such readily available decorative elements? Editor: That makes me think about the copyright issues that must have arisen... Was there a concept of intellectual property at this time? Curator: An emerging one. Printmakers sought protections, but enforcement was challenging. This contributed to the artistic ferment. Artists borrowed freely, transforming existing motifs. It underlines how art then, like now, operated within networks of patronage, commerce and influence. The "politics of imagery" wasn't just about representing power; it was also about who controlled the means of production and distribution. Editor: It is interesting to view decorative art through the lens of socio-economics; a different way of approaching the image. Curator: Indeed. This isn’t just pretty ornamentation, but a reflection of cultural shifts. Next time, try considering a design element from that perspective.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.