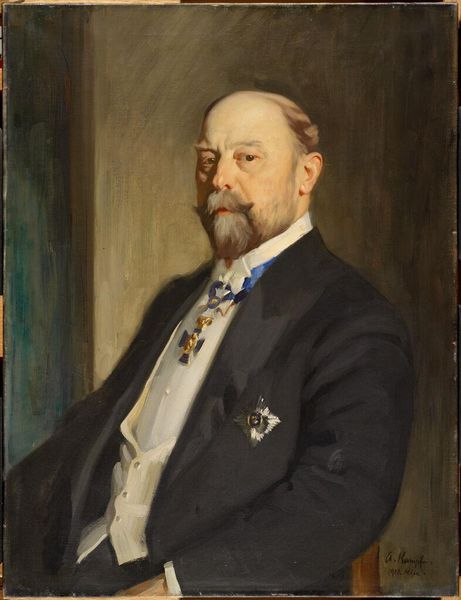

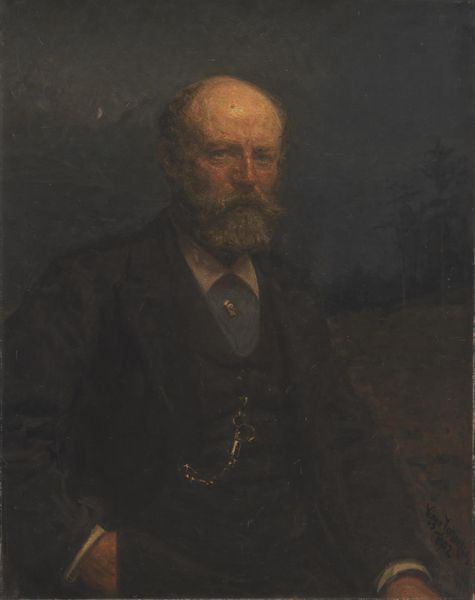

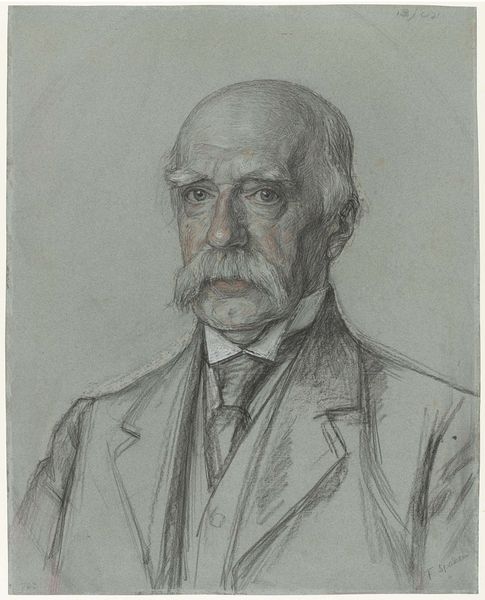

Johan Philip van der Kellen (1831-1906). Directeur van het Rijksprentenkabinet (1876-96) 1904

0:00

0:00

janveth

Rijksmuseum

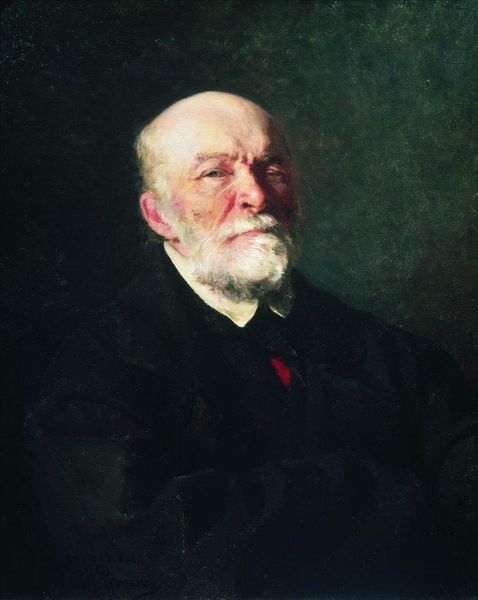

oil-paint, impasto

#

portrait

#

portrait image

#

oil-paint

#

impasto

#

portrait reference

#

portrait head and shoulder

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

facial portrait

#

academic-art

#

portrait art

#

modernism

#

fine art portrait

#

realism

#

celebrity portrait

#

digital portrait

Dimensions: height 65 cm, width 56 cm, depth 7.1 cm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a portrait of Johan Philip van der Kellen painted in 1904 by Jan Veth. The impasto oil paint gives it such a tactile quality. What strikes me most is how his piercing eyes contrast with his soft beard. What do you see in this piece? Curator: For me, this portrait invites questions about artistic labor and the value we assign to both the sitter and the artist. Veth, a respected portraitist, uses oil paint, a material historically linked to wealth and status, to depict Van der Kellen, the director of the Rijksmuseum's print cabinet. What's the labor involved in creating and preserving these images? Editor: That’s a really interesting point! It makes you wonder about the availability and distribution of art resources during this period. Was oil paint readily accessible, or did its cost contribute to a social hierarchy within the art world? Curator: Precisely! The materials themselves participate in this social fabric. Consider the impasto technique – the thick application of paint, making the material almost sculptural. It wasn't just about likeness, but about showcasing the artist's skill and the value of their time and materials. Editor: So, by using this technique, the artist is imbuing more prestige into his own work. It speaks to an art market that values recognizable skill? Curator: Exactly. The value lies not just in representing Van der Kellen, but in showcasing the means of production itself, the very labor and materiality embedded within the paint. The brushstrokes and the artist’s labour become almost tangible. Editor: I hadn’t considered the social and economic context so deeply, I was too caught up in aesthetics. Thank you, this really changes my perspective! Curator: And for me, it is rewarding to see that this particular way of engaging with art may lead one to see it under new, revealing lights.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.