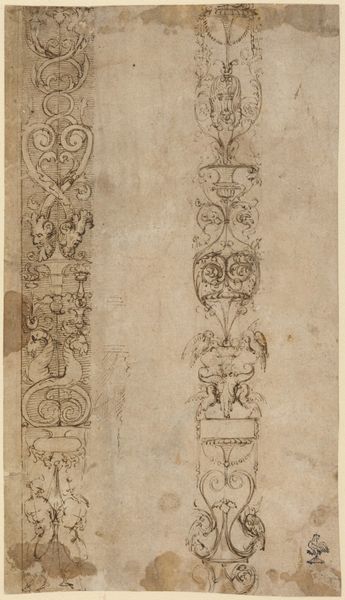

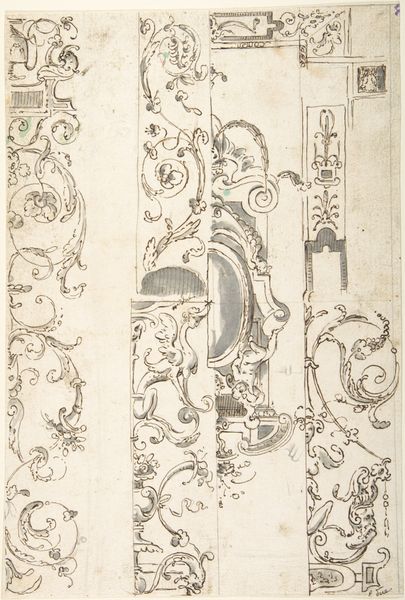

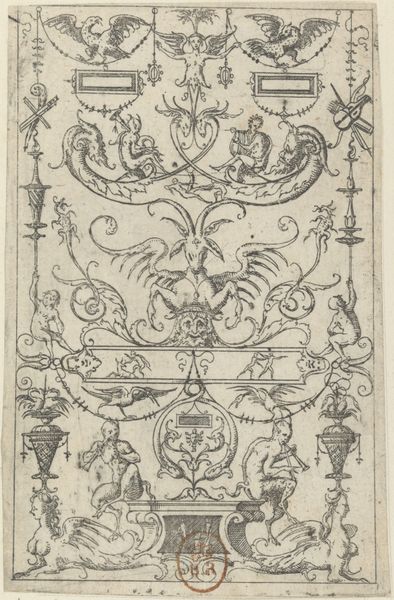

Candelabra grotesque and studies of kneeling figures (recto); two sphinxes (verso) 1540 - 1550

0:00

0:00

drawing, ornament, print, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

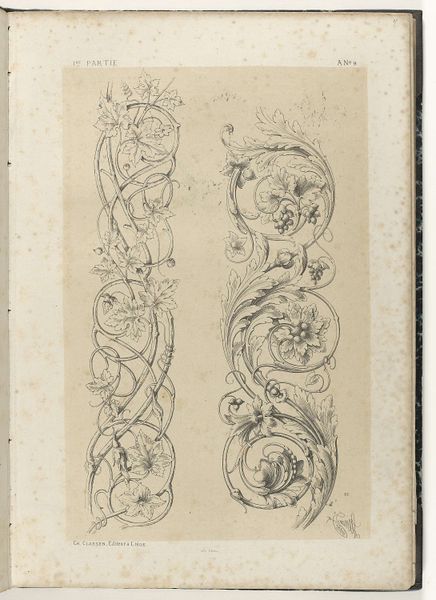

ornament

# print

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

italian-renaissance

Dimensions: 13-3/16 x 8-1/16 in. (33.5 x 20.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This delicate ink drawing from the Italian Renaissance, created circa 1540-1550, is titled “Candelabra grotesque and studies of kneeling figures (recto); two sphinxes (verso)" and attributed to Andrés de Melgar. It's currently held at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It feels...layered. Almost as if I'm looking at the architectural plan for some incredibly ornate, even theatrical, structure, but also at figural studies off to the side. What was Melgar thinking about when he set out to create it? Curator: The candelabra grotesque, that central column, speaks to the Renaissance fascination with classical antiquity, rediscovered in fragments and then reinterpreted through the lens of Christian symbolism. Think about the way ancient Roman motifs became signifiers of power and sophistication. Editor: Exactly, this idea of cultural memory shaping craft, it's visible even in the drawing materials—the ink, the paper itself represents forms of labor, global trade, access to materials. Melgar's social position influenced his very means of creating. Curator: Notice the human figures incorporated into the design of the candelabra, specifically that hybrid woman in the center of the design. These human elements create layers of symbolic association between earthly and divine beauty, wouldn't you say? The figures also represent ideal human form that has been adapted across cultures throughout time. Editor: That's a very loaded concept though, right? Who decided what’s considered ideal? This whole notion feels intertwined with patronage and the status Melgar had at his disposal—perhaps designing for someone, an elite social circle where the display of learnedness was prized. Were these drawings a proposal, or part of his studio practice? What kind of labor was associated with his work, and how was the labor of art-making conceived? Curator: These drawings, and many others that meld classical, pagan and Christian visual vocabulary, offer us ways of reading period expectations for learning and cultural norms. These motifs are repeated throughout history, suggesting collective cultural patterns in human experiences. Editor: Seeing how this period integrated diverse symbolic language and artistic making—we understand better how intertwined the social, material, and cultural spheres were, giving more insights to their own production and forms of exchange in 16th-century Italian societies. Curator: It offers us insight to how meaning, across a long period, gets imbued to visual form. Editor: And also reminds us to think critically about the power dynamics embedded in art making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.