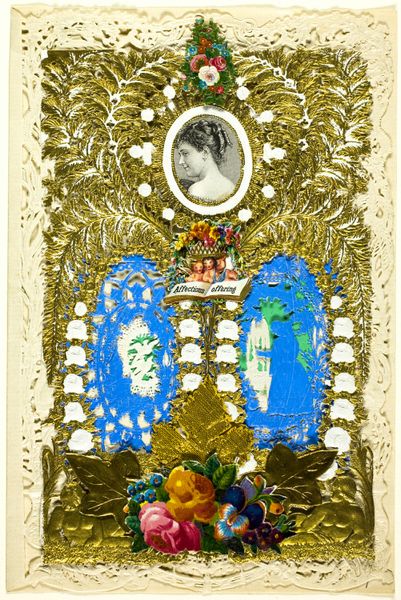

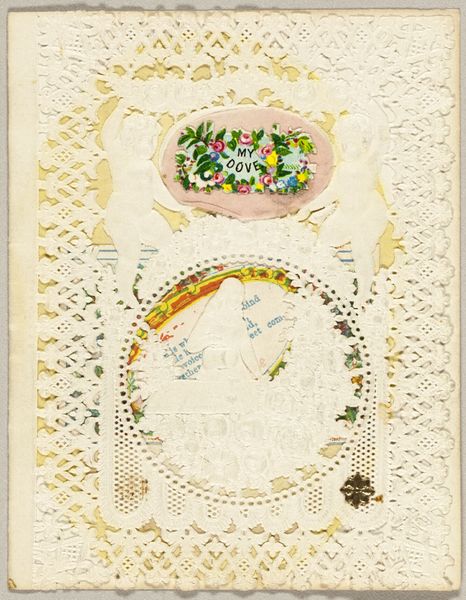

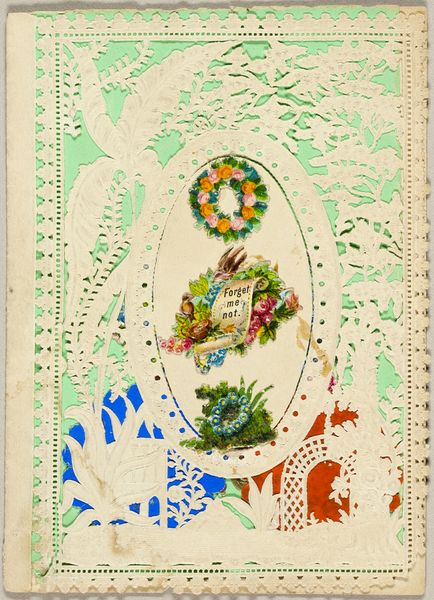

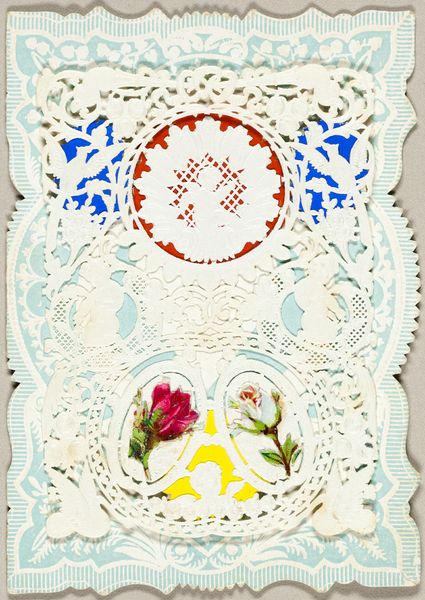

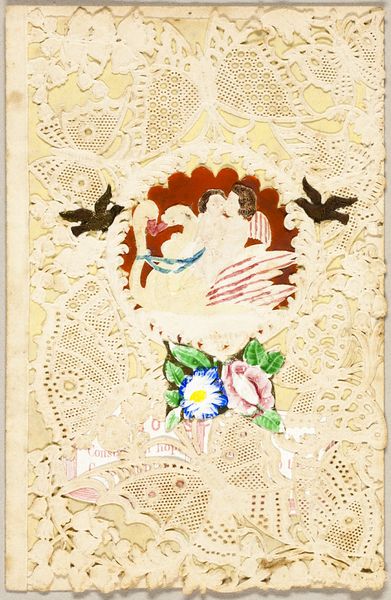

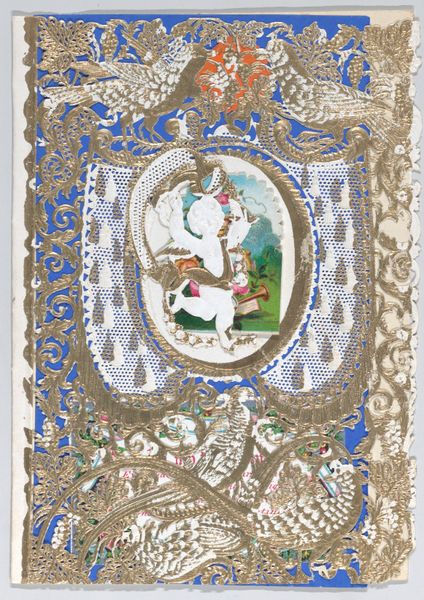

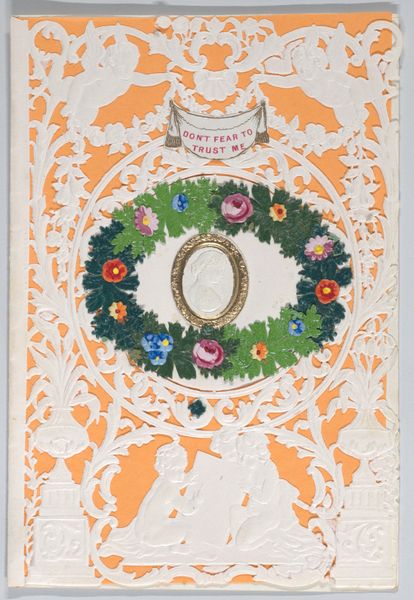

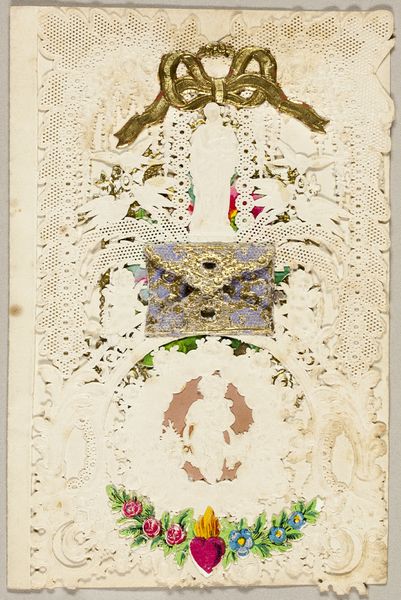

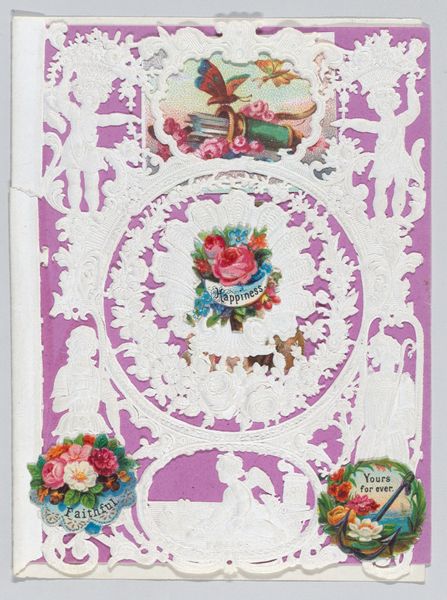

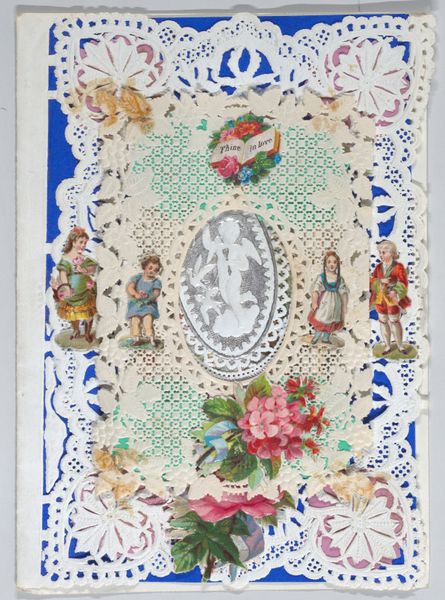

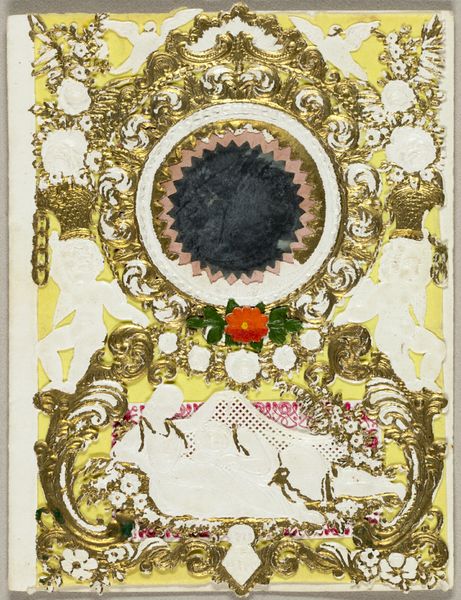

Dimensions: 93 × 72 mm (folded sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Truly Thine (valentine)", an English greeting card created around 1860, now residing here at the Art Institute of Chicago. It’s a striking example of Victorian sentimentality, wouldn't you say? Editor: It is! My immediate impression is the intense detail. All that layered paper, the cutouts, the different textures... It speaks to a labor of love, literally. It really highlights the Victorian interest in the material world. Curator: Precisely! These elaborate valentines were quite the trend in the mid-19th century. Mass production meant materials were relatively accessible, but constructing these cards still signified dedication and social status. The imagery itself—cherubs, doves, flowers—reinforces prevalent ideals of romantic love and domesticity of the period. Editor: That’s a great point. How was something like this fabricated, though? Were different papers sourced locally or did they have to rely on outside vendors, potentially overseas for rarer components like metallic foil? That kind of material reality tells us a lot about consumption at the time. Curator: These valentines circulated within specific social networks and operated almost as performances of affection. Sending such an intricate piece publicly displayed one’s taste, refinement, and, crucially, financial capacity. It says "I care, and I can afford to show it". Editor: And it speaks volumes about craft traditions too. This wasn't seen as high art, right? More aligned with female domestic skills perhaps? Where were women situated in the manufacturing and reception of pieces like this? Curator: Victorian society relegated such activities to the domestic sphere, yes. However, some women undoubtedly commercialized these skills, creating cards for sale. Examining who benefited from this trade reveals some really interesting socio-economic dynamics at play. The production involved various levels of artistry and the marketplace had implications for gendered labor. Editor: Exactly! These material objects carry immense social weight; examining labor alongside materials, especially concerning who produced what and under which constraints, unearths buried social structures that the surface aesthetics tend to conceal. What looks beautiful on its face could indicate exploitation further down the supply chain. Curator: Thinking about the exchange and collecting surrounding these cards as valuable historical objects complicates notions around value, display, and who determines what constitutes art. It opens up all sorts of important critical discourse. Editor: I agree. Delving into process exposes these objects' profound connection to societal forces shaping not just consumption, but social order, which the delicate beauty and overt themes of affection only partially hint at. Curator: So true. Well, perhaps now we have given listeners a richer perspective from which to appreciate its surface and consider its depth. Editor: I hope so, that they leave considering not only what the artwork portrays but also the how, where, and who that constitutes its complex materiality.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.