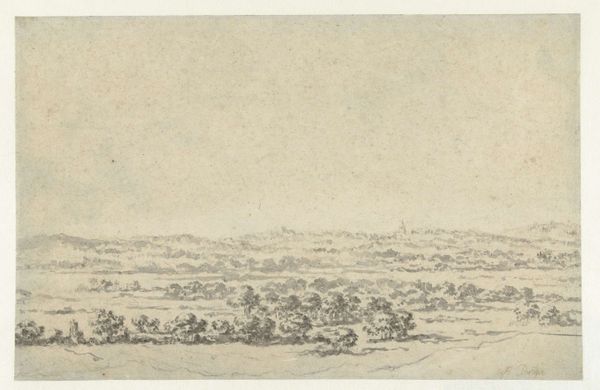

drawing, pencil

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

pencil

#

early-renaissance

#

realism

Dimensions: height 138 mm, width 265 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This delicate pencil drawing is entitled "Landscape with the Ponte Milvio, outside Rome" and it was created by Gerard ter Borch the Elder in 1609. What’s your first impression? Editor: It feels incredibly serene and observant. There's a vastness communicated through the simple, yet detailed rendering. But tell me, what was ter Borch Sr.’s engagement with this locale and why a seemingly mundane subject like a bridge? Curator: Ter Borch, of course, was a prominent figure within the Dutch artistic milieu, even though not often foregrounded relative to his more successful son. He spent time in Rome around this period, where, evidently, he adopted a particular method. Pencil sketches, especially landscape studies, were becoming increasingly important as a stage in the artistic process, allowing artists to rapidly document impressions and motifs. The choice of Ponte Milvio underscores the shift from idealized to observed landscapes; it is rendered less as a symbolic location than as part of the material environment, almost. Editor: This piece speaks to broader historical narratives of power and transit that shape communities. The Ponte Milvio wasn't just any bridge, was it? Ancient roots, crucial Roman artery, even witnessed a pivotal battle that solidified Christianity. I wonder how those echoes shaped Ter Borch's rendering of it—how did it resonate within its layered cultural, religious, and colonial history? Curator: Exactly, to understand fully, we can’t detach the bridge's structure and function from the economic flows it once facilitated. Note, for instance, the level of detail invested in depicting fields in the immediate foreground, each section marked with subtle variation of light. And pencil allows this subtlety; we get linear hatching delineating plots and topographical undulation—visible and tangible labor through mark-making. Editor: And those topographical details hint at how land is used, organized and claimed—it underscores material ownership and production and extraction, reflecting how rural agrarian landscapes relate to the socioeconomic context of seventeenth-century Rome. It is not, though, entirely topographical accuracy that Borch is after, wouldn’t you say? Curator: Certainly, it's not a precise topographical survey, nor an idealized vista. The pencil sketch captures lived engagement between artist and environment within broader historical and cultural forces shaping perception and visual representation. Editor: I see in the careful strokes the complexities and histories embedded in a seemingly quiet landscape. Curator: And I think the drawing also forces us to see that art is created through a complex mesh of ideas and real working and access conditions. It urges us to appreciate what pencil sketch contributed to the artistic practice, at that moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.