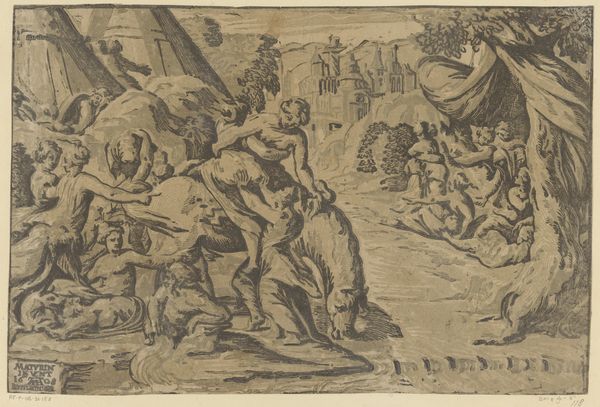

Water, represented by a naiad seated at the base of a tree and resting her arm on a supine urn from which water flows, behind her a triton and other inhabitants of the sea rise from the water surface, from "The Elements" 1640 - 1660

0:00

0:00

print, etching

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

mythology

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 4 1/8 × 5 13/16 in. (10.5 × 14.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This etching, "Water, represented by a naiad..." comes to us from Giulio Carpioni, dating back to the mid-17th century. It's part of a series called "The Elements." What strikes you first? Editor: The density, almost oppressive—a mass of bodies swirling around this central, strangely passive, female figure. The etching lines create such a textured, almost claustrophobic space. Curator: It's an intriguing mix of classical allegory with the tactile reality of printmaking, isn't it? Consider the availability and cost of printed material in Carpioni’s time. It was relatively democratic as compared to other media such as painting or sculpture and thus widely disseminated. Etchings like this broadened exposure to mythological and allegorical scenes, effectively circulating cultural narratives among different social strata. Editor: Absolutely, the medium itself informs the message. This depiction of "Water" and the naiad feels less like a detached, idealized form, but is embedded in the social and cultural understanding of water as resource, and possibly the feminine. The naiad, the water sprite, embodies nature, while those around her struggle or play; they are active agents consuming this resource. What about gender roles and dynamics within the context of Baroque society? Curator: A valid and relevant question, certainly. Water sustains life, and its symbolic ties to fertility are strong. The female figure pouring the water seems almost worker-like when we focus on her gesture of continuous supply as physical labor. Note the production effort: the biting of the acid on the metal plate, the controlled application of ink, and then pressing it into paper to allow a number of people to appreciate it. It really speaks to the democratizing aspect of material availability. Editor: Agreed. Looking at her detached gaze, the power dynamics at play emerge into sharper focus. Who has access to, and control over, this vital resource? How does it shape relationships of power and dependency, visible in those clamoring for water around her? It pushes us to think about water rights, then and now. Curator: Right, it's easy to be pulled in by the mythological content, yet crucial to think through the realities of labour involved and material consumption during that period. We see mythological allegories in countless mediums, yet prints uniquely carry a social dimension linked to its reproducible and easily distributed qualities. Editor: Indeed, examining this from both perspectives – the historical context and material reality of the etching—deepens our understanding. The artwork serves as a lens to analyze social dynamics, environmental consciousness, and our own relationship with resources. Curator: A fascinating intersection. Let us turn our attention to our next work on display.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.