painting, oil-paint

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

painted

#

figuration

#

oil painting

#

underpainting

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

painting painterly

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

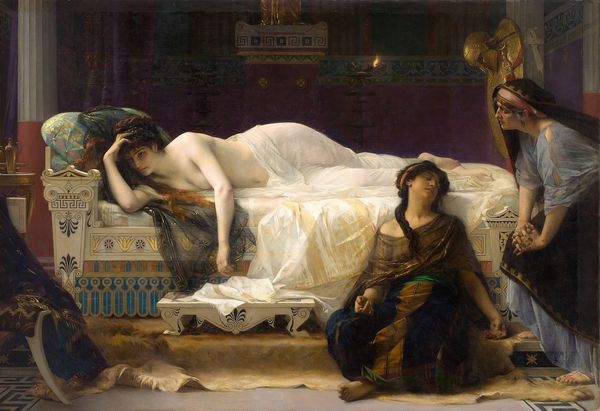

Curator: Immediately, I feel swallowed by dread looking at this scene. The muted colors and shadows heighten the somber mood, hinting at unspeakable tragedy. Editor: Well, it certainly aims to convey a significant weight. This is "The Death of the Pharaoh’s Firstborn Son," an oil painting created in 1872 by Lawrence Alma-Tadema, a painter known for his meticulously rendered historical scenes. Curator: Tadema definitely leans into depicting historical narrative, especially around classical and ancient settings. Look at the composition! He carefully captures the moment, yet all the signs point towards death – a palpable void, like the aftermath of some ancient horror. Editor: The painting taps into a very specific biblical narrative – the tenth plague of Egypt, where God inflicts the death of firstborn sons upon the Egyptians as the final catalyst for the Exodus. This episode has echoed across Western art and culture for millennia, solidifying its position in shared cultural memory. Curator: Absolutely. Think of the sheer symbolism: death as divine retribution, leadership facing loss. Even the single flower that the Pharaoh holds suggests that finality. In the psychology of symbols, flowers often relate to death as a moment of temporary bloom before an ending. And his upright position juxtaposed with the slumped figures accentuates themes of powerlessness in the face of the inevitable. Editor: I agree. It’s intriguing how Alma-Tadema translates that symbolic language for a Victorian audience grappling with its own imperial anxieties. Scenes of empire are not limited to celebrations of triumphs. Rather, works like these presented anxieties about loss, power, and divine mandate, repackaged within grand historical tableaux to comment on contemporaneous issues. Curator: It prompts me to reflect on our obsession with representing grief visually, particularly how societies handle trauma at a grand scale. Even in art, the shared pain becomes its own symbol. Editor: Precisely. This painting functions as a lens. Looking back at the historical plagues, and indirectly pointing a finger at Victorian-era imperial confidence. History gives context to the contemporary moment. Curator: Looking at the composition, one starts to perceive what symbols connect, and through it, emotional responses that transcends centuries and cultures. That is what ultimately moves me about this work. Editor: Yes. It shows the powerful political messages woven within classical paintings like this; something that lingers, even after we step away.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

In this scene from the biblical book of Exodus, Moses and Aaron (upper right) visit the pharaoh, who is mourning his son. The Egyptian ruler’s son had died from one of the plagues sent by God to secure the Israelites’ release from Egypt. The gloom of the painting reflects the father’s intense grief. One has to look long and hard to discern all the figures and details.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.