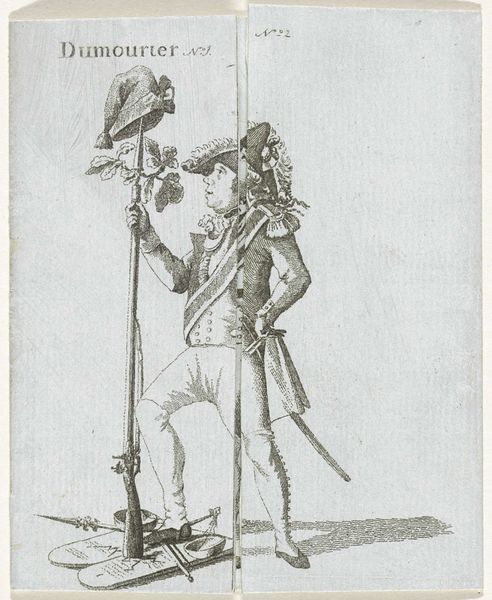

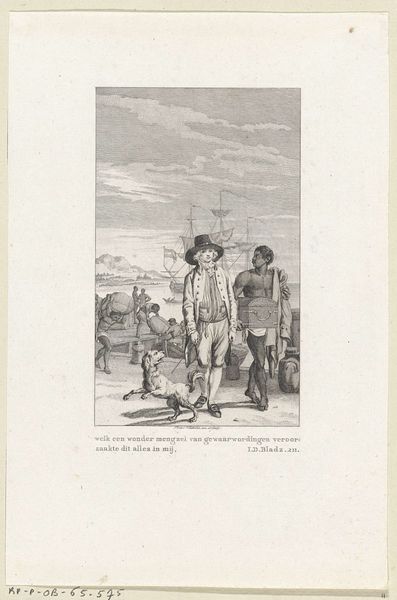

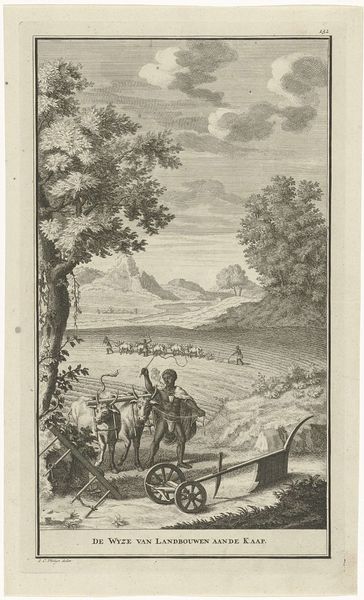

print, engraving

# print

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

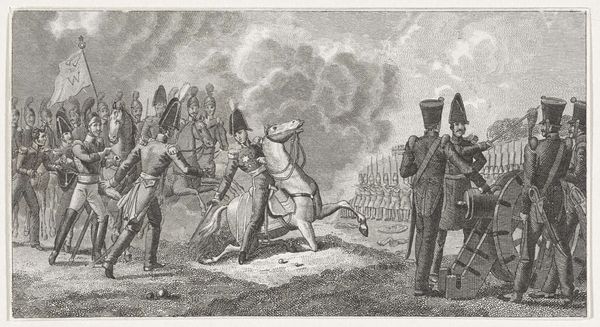

romanticism

#

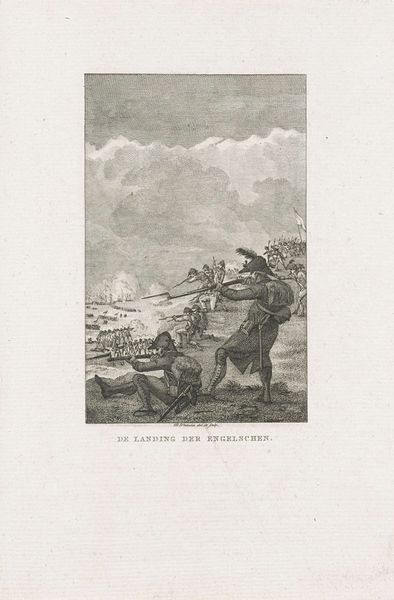

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 65 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, simply titled "Soldaat met geweer" or "Soldier with Rifle," comes to us from the period of 1815 to 1840. The artist is Johannes Steyn, and it currently resides here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My immediate reaction is… disquieting. The rigidity of the soldier contrasted with the labor of the enslaved person in the background generates this undeniable tension. The lines feel so deliberate, sharp even. It’s unsettling. Curator: It’s a potent image, no doubt. Consider the historical context; this work emerges during a period of significant political and social upheaval following the Napoleonic Wars, a moment when notions of national identity were being fiercely contested and militarism romanticized. Notice how Steyn utilizes the stylistic features of Romanticism—that emphasis on emotion and the power of nature reflected in the threatening sky above, for example—to perhaps subtly glorify this soldier's role in defending… something. Editor: Glorify? Or perhaps reveal? I see less glory and more exploitation embedded in the visual composition. An enslaved person straining under the weight, seemingly connected to a cannon, juxtaposed with a soldier posturing with a rifle – the image speaks volumes about power structures predicated on inequality. It feels like a not-so-subtle commentary on who truly bears the burden of empire and nation-building. I read a very uncomfortable statement about colonialism there. Curator: That’s a fascinating reading, and certainly valid considering the socio-political currents of the time. The choice of line engraving too adds another layer. That precise method lends the scene an almost clinical detachment even if it also recalls grand history paintings in the artistic vernacular. It allows for details, yet distances the viewer from the implied violence. Editor: But clinical detachment normalizes such scenes! Isn't the true violence in how such brutal realities can be coldly rendered, consumed, and displayed? Think about the ways images can normalize exploitation... How this could even be understood as a neutral representation is deeply concerning to me. Curator: It raises difficult questions about representation, doesn’t it? The interplay between art, power, and historical narratives. It gives me pause to consider how this piece existed as public imagery in its era and how it impacts its meaning and reception. Editor: Exactly. Even today, we grapple with how we contextualize artworks rooted in oppression. We must ask ourselves, "What stories do we want to tell, and whose voices do we elevate when exhibiting art such as this?" Curator: It's a chilling reminder that art is never truly neutral. Editor: Never neutral, always implicated.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.