Dimensions: height 139 mm, width 139 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

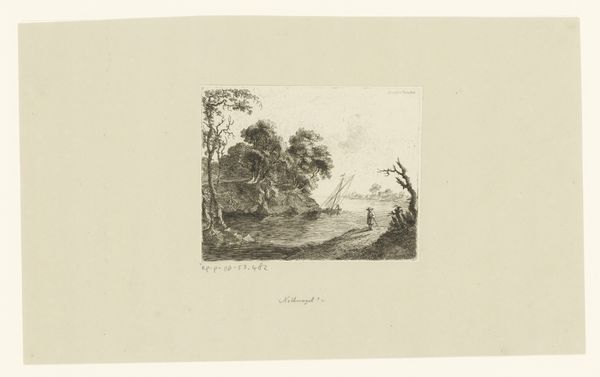

Curator: This is Henri Toussaint’s "Rivierlandschap met kasteel bij maanlicht," a river landscape with a castle by moonlight, created in 1881. It’s an etching on paper. Editor: My first impression is of quiet unease. There’s something romantic, yes, but also brooding, even threatening, in the way the moonlight falls across the water. Curator: The choice of etching is crucial here. Think of the labor involved in carefully creating the plate, line by line, using acid to bite into the metal. The print then allows for dissemination of this somewhat unsettling Romantic vision. Editor: I'm struck by how the scene’s inherent romanticism serves to also illustrate power and its means to material consolidation; a distant castle oversees lands, people, resources, under the guise of natural beauty. The artist then literally disseminates the image into material commodity by virtue of this printing. Curator: Precisely! Toussaint is engaging with Romanticism, but there is also a clear commentary, perhaps unintentional, on labor and class. He seems to echo class inequality. The distant castle underscores existing social hierarchies. The darkness makes these class relations almost…dangerous. Editor: And we can’t ignore the printmaking itself as a material process – the paper, the ink, the press, the work involved in its production. Who was intended to purchase it, who could afford it, and how was it circulated through markets or social networks? Curator: Those are key questions, aren’t they? Think of the gendered implications, too: women relegated to more delicate, detailed artistic processes such as embroidery whereas the physically intensive activities of printing would probably remain the arena of men, solidifying the social implications. This isn't just a landscape; it's a landscape imbued with social meaning. Editor: Definitely. It reflects both artistic intention and wider societal realities through material practices and artistic distribution. Curator: Ultimately, examining this print pushes us to question whose perspective is centered and who benefits from romanticising these kinds of scenes, especially when contextualizing social issues surrounding race, class and gender. Editor: A fine point! Considering all its historical layers of value and values truly amplifies this work far beyond its pretty aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.