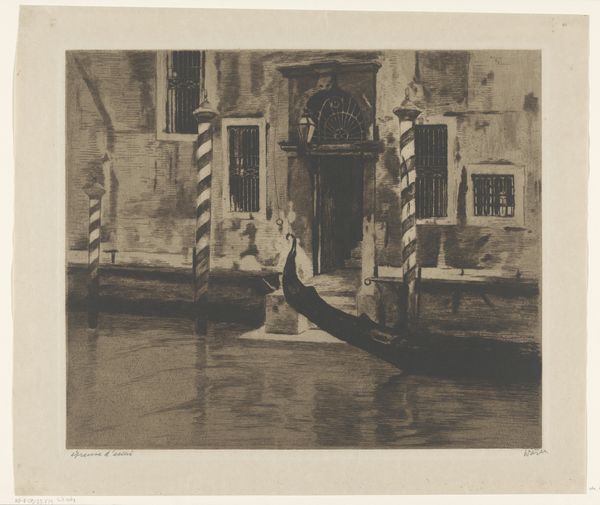

Dimensions: 13 x 10 5/16 in. (33.02 x 26.19 cm) (image)19 3/4 x 15 11/16 in. (50.17 x 39.85 cm) (sheet)

Copyright: No Copyright - United States

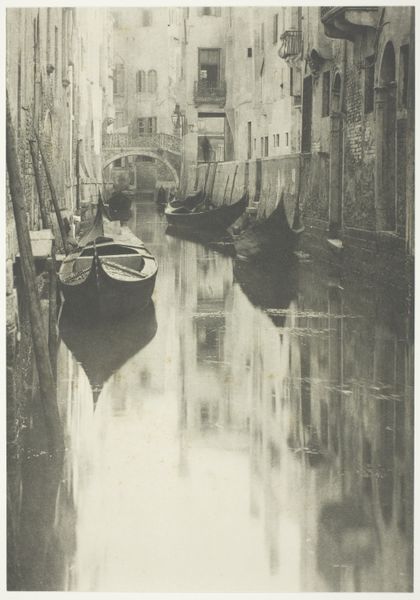

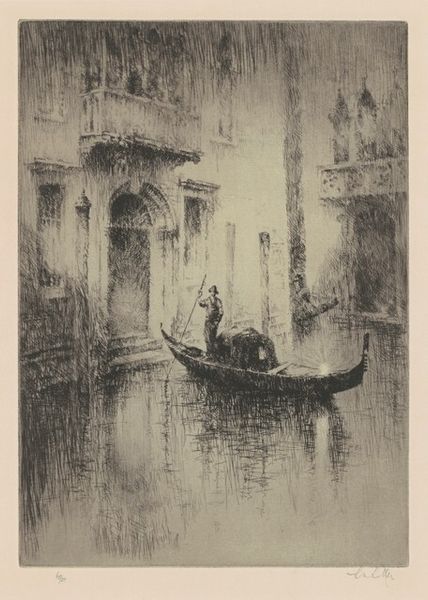

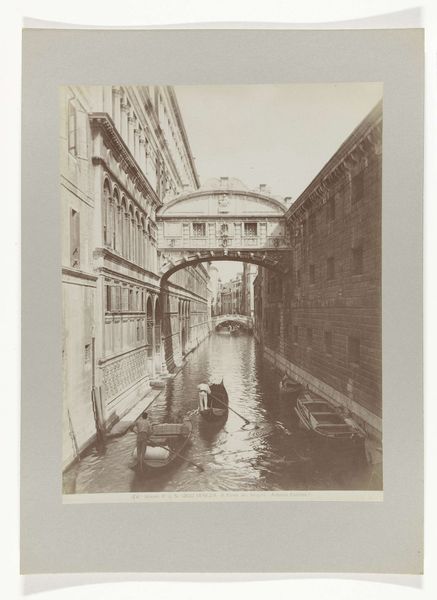

Curator: Welcome. We're looking at George C. Poundstone's photograph, "A Doorway," a gelatin-silver print created around 1934. What’s your initial read? Editor: A somber stillness pervades the scene. The narrow waterway and looming architecture almost feel claustrophobic. There is a vulnerability embodied in the laborers—or travelers, rather—that compels reflection on labor, class, and precarity during the interwar era. Curator: The composition certainly reinforces that sense of enclosure. The high contrast accentuates the geometry of the architecture, almost overwhelming the human figures in the boat. It’s a study in spatial relationships, wouldn't you say? How Poundstone directs our eye from the bright doorway, down along the canal, noticing that the laborers inhabit but a small plane amid towering infrastructure... Editor: But shouldn’t we be attentive to what such a photograph means? This image evokes questions of urban poverty and social stratification in Venice at a time when such idyllic depictions concealed socioeconomic rifts. What were the actual lived experiences of individuals navigating Venice’s intricate web of waterways? And how did the rise of industrialization affect that? Curator: You raise an important point about historical context. Yet, beyond that reading, the textures! Look at the ripples in the water compared to the worn stone of the buildings, and how the light plays off both. Semiotically, consider the closed door and its promise—or denial—of entry. Doesn’t that visual paradox resonate beyond a mere social document? Editor: Undoubtedly, there are interesting aesthetic tensions, but I still come back to its underlying message about marginalized people inhabiting a luxurious city in economic decline. The human element within architectural dominance carries immense weight, offering visual commentary on themes like social division. Curator: I appreciate you widening the discussion, even as I find merit in closely unpacking the work's formal mechanics, of shape and light. Thanks for lending that perspective. Editor: Indeed, a constant dialectic is good. Thank you; seeing art in light of history helps better understand us, even today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.