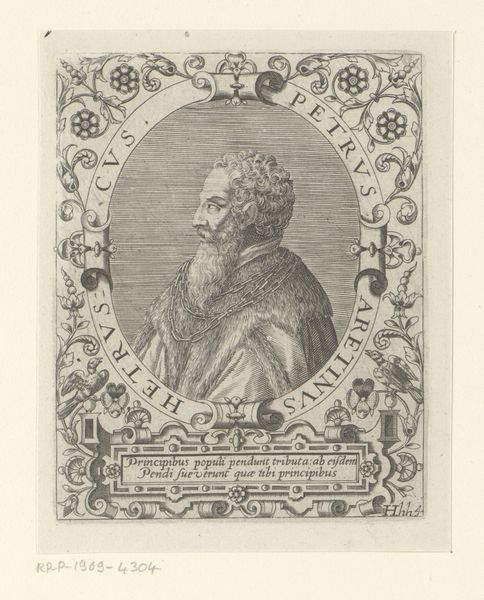

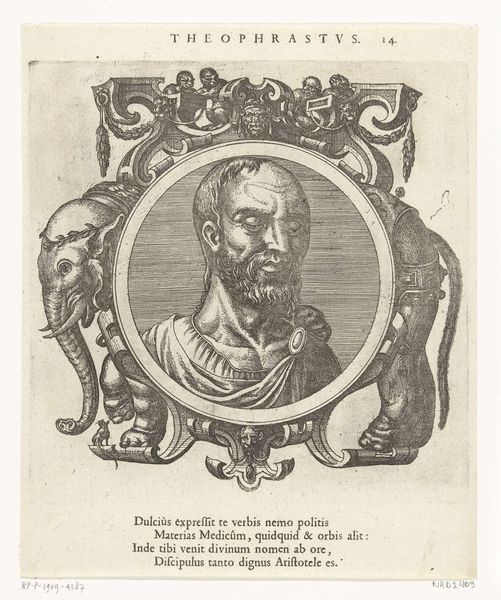

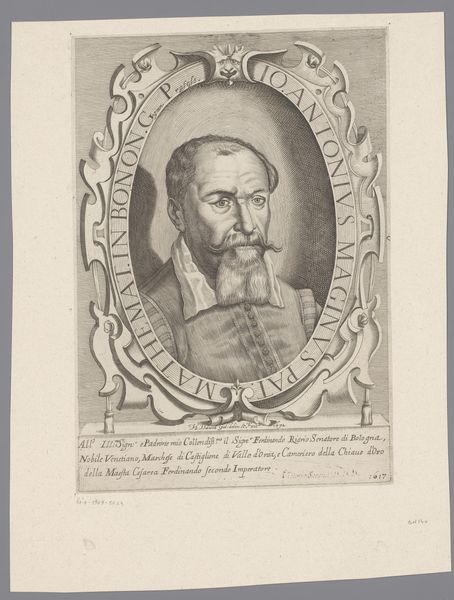

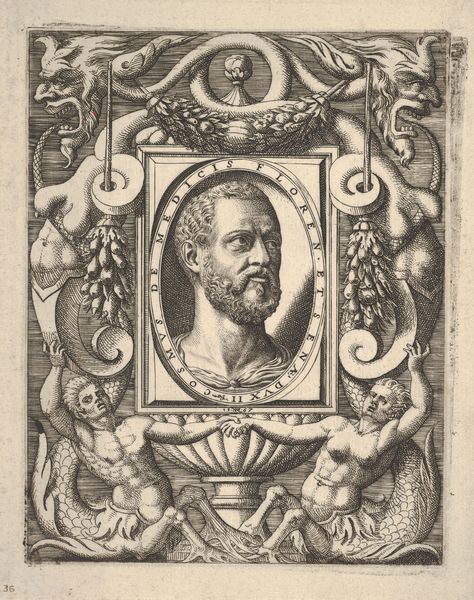

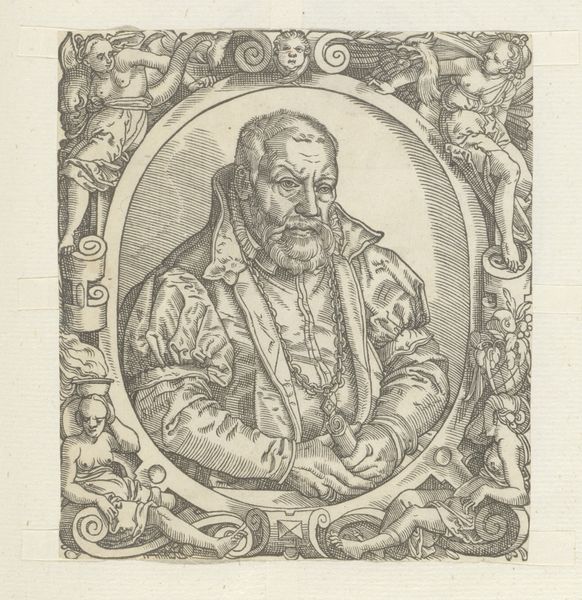

print, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

old engraving style

#

caricature

#

11_renaissance

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 152 mm, width 113 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

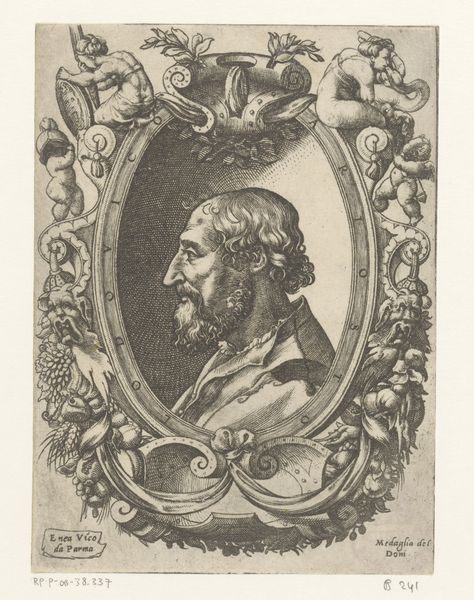

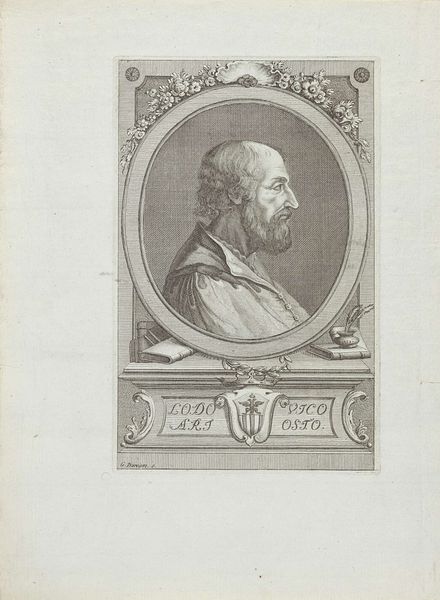

Editor: This is a portrait of Cipriano Moresini by Enea Vico, made in 1550. It's an engraving, so a print. The detail is incredible, and I'm struck by how intricately the frame is decorated. What's your perspective on this print? Curator: Well, let's think about the labor involved. Each line painstakingly etched, multiple impressions made. The economic implications of printmaking during the Renaissance are huge. Consider the material: copper. Where did it come from? Who mined it? This engraving facilitated the *distribution* of Moresini's image – and, significantly, Vico's artistic brand – far beyond Venice. How does that affect our understanding of portraiture's function here? Editor: That’s a completely different way of looking at it than I’m used to. I was focused on the sitter, his status, and maybe Vico's skill. Curator: Exactly! But think about how the mass production changes everything. A unique painted portrait served one patron, cemented their power within a small circle. Prints? They’re about a different kind of power: the power of dissemination, of a market, of potentially wider recognition. How does that change the role of the artist, of the subject, of the *viewer*? Editor: So you're saying it's not just about the image, but the means of production and how it changed the art world? Curator: Precisely! The lines themselves *are* significant. We need to look beyond aesthetics, to ask *how* that image came into being, what it *did* in the world. And for whom. Editor: This is eye-opening. I’ll definitely rethink how I look at prints, focusing more on the process and context. Curator: Excellent! It transforms our perception. Considering materials, methods, and markets truly makes Renaissance prints even more interesting.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.