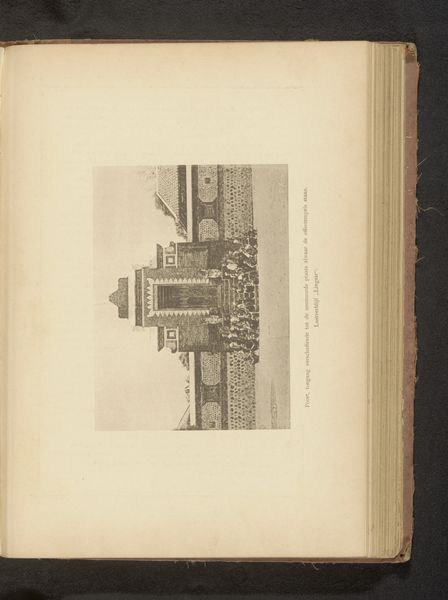

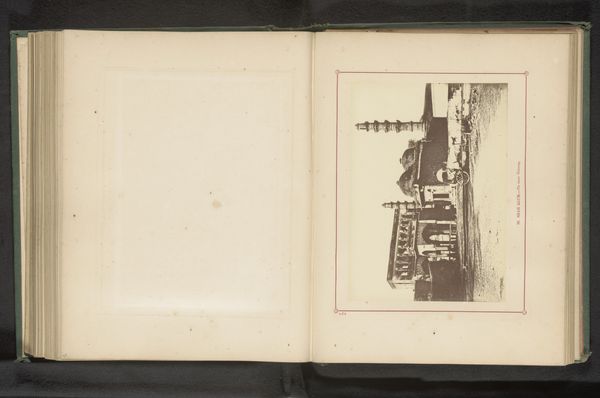

photography, albumen-print

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

cityscape

#

islamic-art

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Francis Frith's "View of the Great Mosque of Damascus," a photograph dating from around 1850 to 1865, housed right here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The sepia tones give it an immediate sense of age and distance, don’t they? It feels like looking at something irretrievable. Curator: Indeed. Frith was one of the first British photographers to travel extensively in the Middle East. Think of the logistical challenge involved in carrying heavy photographic equipment across vast distances to document the region's architecture and cityscapes. This view, an albumen print, speaks to that effort. Editor: The albumen process is crucial here. The egg whites used as a binder contribute to the photograph's stability, but it also has an effect on its visual properties, producing such a subtle range of tonality. How do you consider Frith’s role as not just a photographer but as an industrialist and entrepreneur? Curator: His ambition and business acumen shaped the consumption and perception of the "Orient" in Europe. His studio mass-produced these images, fulfilling a growing demand for visual representations of faraway lands that would promote the exotic and the imperial project. It reflects a societal fascination but also solidifies the orientalist imagery through material accessibility. Editor: And those meticulously rendered architectural details - the minarets piercing the skyline. Was he interested in its function? I wonder if he thought of the labor required to produce it and its symbolic, functional role to the community, not as an abstract notion but as material and physical. Curator: It's a question of agency. Frith may have romanticized Damascus, but he also provided a valuable visual record of a city undergoing rapid transformation in an age of expanding empires and industrial output. How does that contribute to our comprehension of these places at the intersection of image making and societal forces? Editor: It's complex. The print serves as both a window into the past and a reflection of the forces that shaped our perception of it. Understanding Frith's own investment – the financial and colonial framework – gives new understanding into this representation of cultural heritage. Curator: Seeing the role that photography plays in shaping those perceptions is crucial, providing access to this monumental landmark and allowing the public to think critically about representation. Editor: Yes, considering the photograph's materiality, the actual process and distribution behind it gives new light to a place we will most likely never encounter, which will invite conversations about how history is perceived.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.