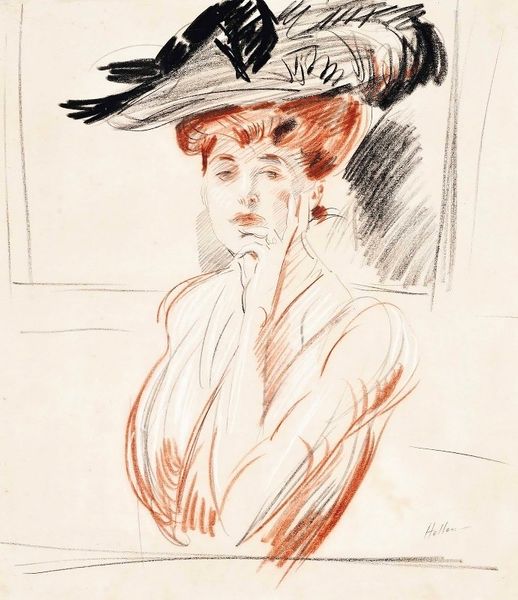

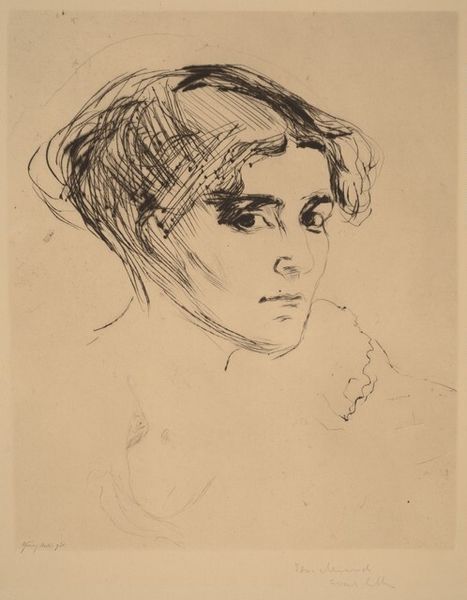

drawing, print, paper, charcoal

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

new-objectivity

# print

#

german-expressionism

#

paper

#

pencil drawing

#

expressionism

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

Dimensions: sheet: 40.7 × 30.8 cm (16 × 12 1/8 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Editor: We're looking at Otto Dix’s "Lady in a Feathered Hat," created in 1923 using charcoal, pencil, and print on paper. There's a starkness to this portrait, a sense of unease beneath the surface elegance. How do you interpret this work, especially considering its historical context? Curator: Dix, emerging from the devastation of World War I, was deeply critical of Weimar society. The portrait, rendered in such a raw, almost brutal style, is less about individual beauty and more about the social and political realities of the time. The elaborate hat and makeup are superficial masks, and Dix's harsh lines strip away the illusion. Editor: So, it's a critique of the artifice and decadence of the Weimar Republic? The war's effects linger, even within these superficial displays? Curator: Precisely. Consider the political instability, hyperinflation, and moral decay prevalent then. Dix and his contemporaries sought to expose the dark underbelly of society. This image participates in that discourse, rejecting traditional idealized portraiture in favor of a confrontational, unflinching depiction. Is she powerful or vulnerable, do you think? Editor: I see a strange mix of both, actually. The hat feels like a shield, yet the downward gaze hints at a fragility. Maybe it’s commenting on the precarious position of women during that era, caught between tradition and newfound freedoms. Curator: It absolutely speaks to that tension. The “New Woman” was both celebrated and scrutinized. Dix captures that complexity. How do you feel the social and artistic institutions shaped his image, and, ultimately, its meaning? Editor: Thinking about it now, it seems the museums showcasing artists like Dix were actively engaging in political discourse by choosing to display such challenging works. This drawing becomes more than just a portrait, it's a social commentary broadcast by its exhibition, almost a document of the art world. Curator: Exactly. And Dix himself intentionally subverted the traditional patronage system, creating works that challenged the status quo and forced the audience to confront uncomfortable truths. Editor: I hadn’t fully considered how much the historical context and display settings can influence our perception. This has given me a whole new appreciation for Dix’s work and its political implications. Curator: It highlights how art can reflect and shape our understanding of the world, far beyond mere aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.