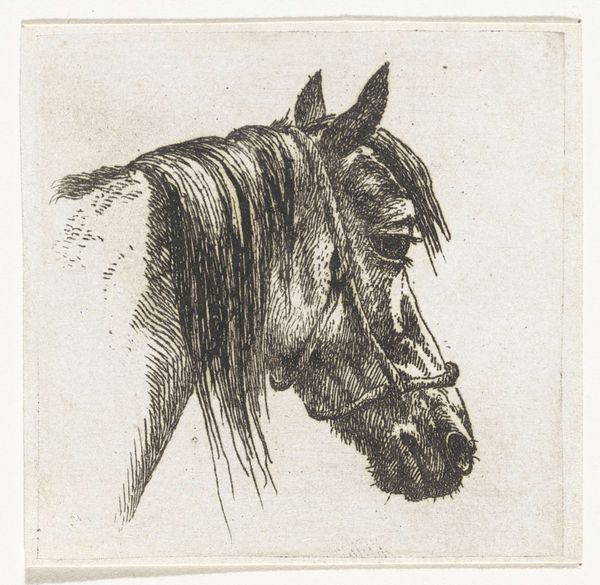

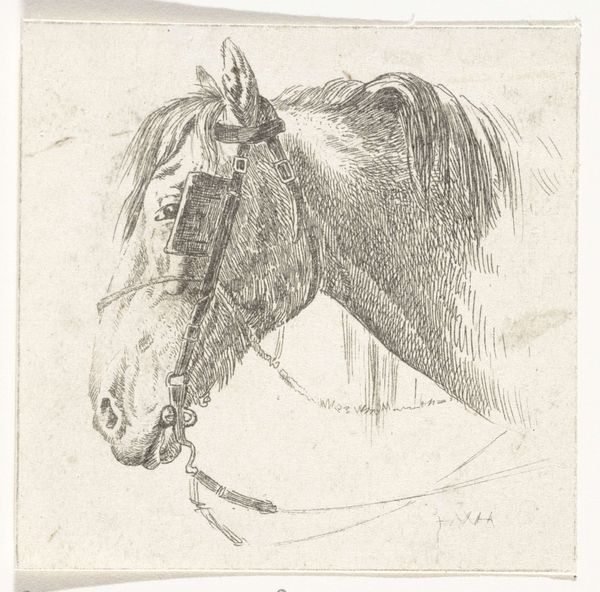

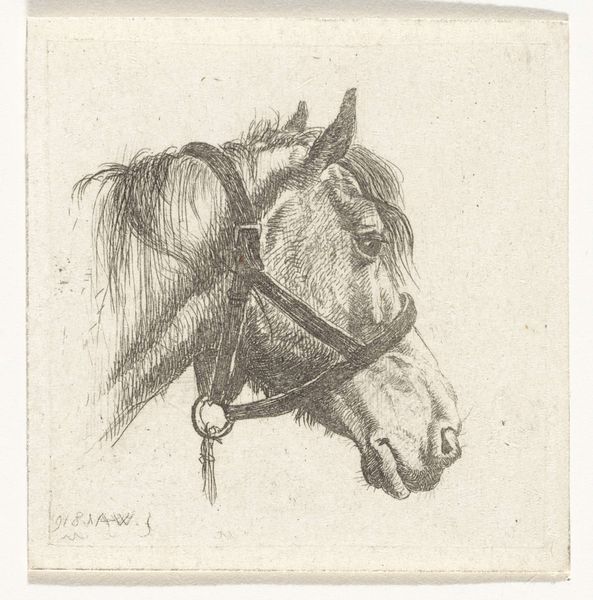

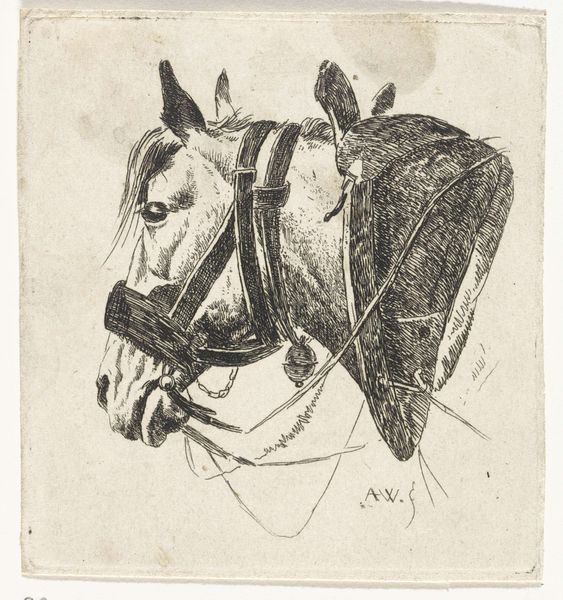

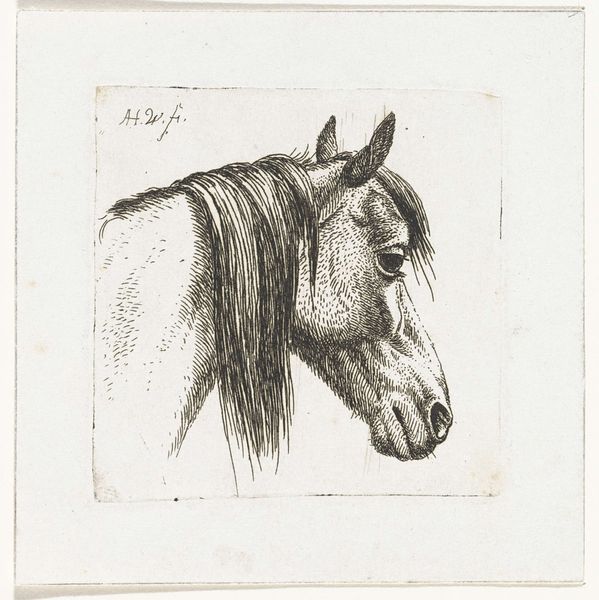

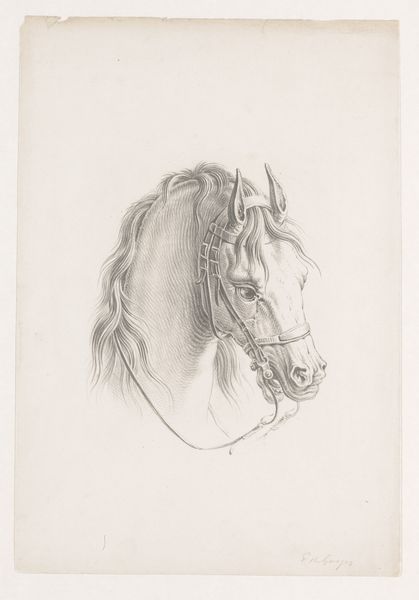

drawing, etching

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

animal

#

etching

#

figuration

#

horse

#

line

#

realism

Dimensions: height 123 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Before us, we have "Paardenhoofd," or "Horse's Head," by Arnoud Schaepkens, likely created sometime between 1831 and 1904. It’s an etching. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: It strikes me as surprisingly raw. The lines are so direct, almost harsh. You can almost feel the weight of the etching plate, the artist pressing into it. There is something honest and brutal about it. Curator: It's interesting you say that. Consider the period it was likely made, within the 19th century’s artistic landscape, especially regarding the depiction of animals. Horses, often symbols of power and aristocracy, are given this stripped-down, almost utilitarian representation. What statements are being made regarding labour and representation? Editor: Good point. Etching as a medium lends itself to reproduction, creating multiples. It becomes accessible in a way an oil painting of a horse never could be. What would have been the social status of those looking at the animal’s image, considering their interactions with horses as beasts of burden in everyday life? Curator: Precisely! And look at the horse's harness. It's not decorative. This is a working animal. The focus isn’t on romanticizing rural life but documenting the labour integral to its economy. And perhaps offering an understated comment on the social and material realities behind that labor. The subject implicates class and labor in a compelling way. Editor: It prompts one to reconsider how we interact with and represent working animals today, or laborers and machinery involved in agricultural productions. What kind of images come to mind and how are the means of producing such images influencing the aesthetic properties themselves? Curator: Indeed. It calls for a conversation about animal rights, labour exploitation, and representation, connecting 19th-century imagery with present-day social dynamics and intersectionality. Editor: Looking closer, the materiality and process here suggest so much about the period's visual and manufacturing culture and how it framed human relationships to labour in fields far beyond equine ones. Curator: The social and historical roots embedded within this portrait of labor offer pathways to comprehend present dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.