Copyright: Public domain

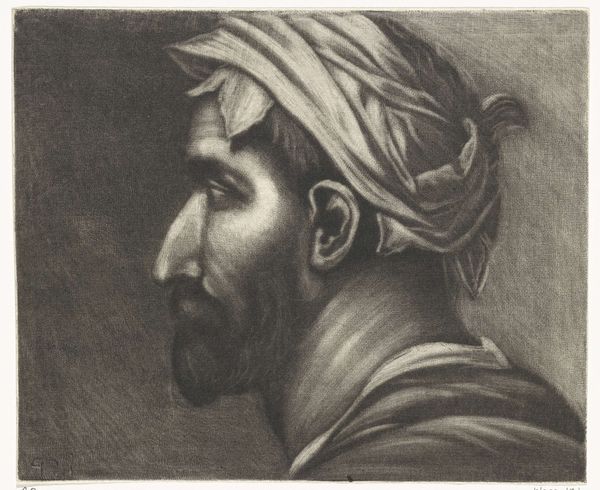

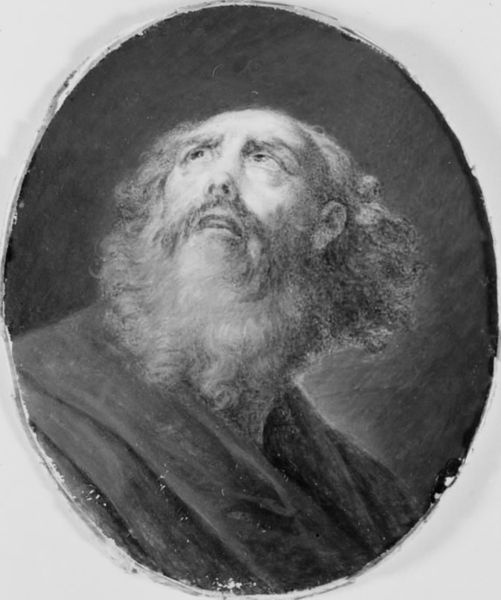

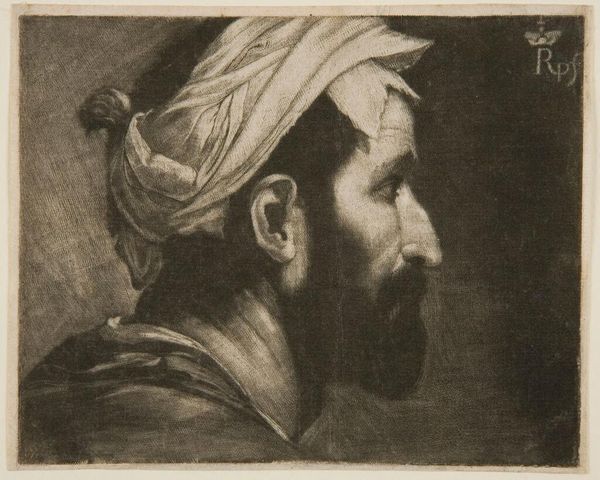

Editor: This is Josef Kriehuber’s Self-Portrait, made in 1852. It's a lithograph – a type of print – that I find quite striking. The detail achieved with what are essentially just stones and ink is impressive. What do you see in this piece from a materialist perspective? Curator: Well, focusing on the lithographic process, we see an example of industrialized art production emerging. The use of lithography allowed for relatively easy reproduction and wider distribution compared to unique paintings or sculptures. Kriehuber was a celebrated lithographer; his workshop and its products deserve scrutiny in that historical and economic context. Editor: So, you're saying that the method of production itself gives meaning to the piece beyond just being a self-portrait? Curator: Precisely. The Romantic era is often associated with notions of the singular artistic genius, yet Kriehuber profited by commodifying his likeness through reproducible printmaking. He’s both artist and entrepreneur using this medium. What impact do you think this commodification had? Editor: I guess that it would make art more accessible, but perhaps also cheapen the idea of the artist? Curator: In a way, yes. It complicates the Romantic ideal by highlighting how artistic identity gets bound up in distribution and economics. He still clearly displays Romanticism through subject and clothing. But, the technique, which enabled circulation, reframes this as both personal expression, and business transaction. What has changed for you seeing the portrait in this new way? Editor: It shows me that understanding the materials and production helps me to consider questions about commerce and accessibility in art, something I hadn’t fully appreciated before. Curator: Exactly! The focus on materials and making can often reveal such interesting dimensions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.