painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

charcoal drawing

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

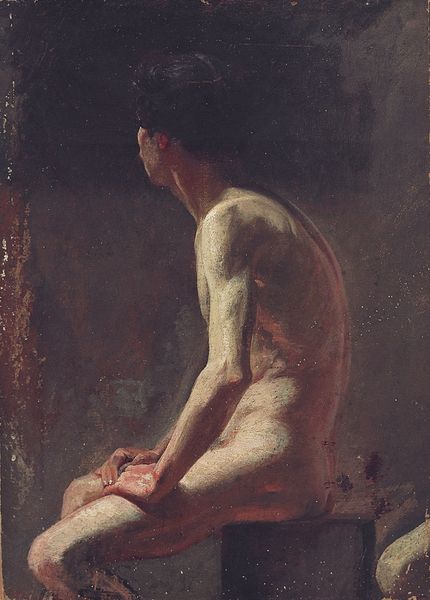

Curator: What strikes me first about Mariano Fortuny Marsal’s “Bust of an Arab Boy in Profile” is its immediacy. It feels almost photographic in its realism, though clearly rendered in oil. Editor: My eye is drawn immediately to the tension between light and shadow, almost like chiaroscuro but with subtle grays. It hints at so much hidden, suggesting a complex inner world for this figure, who's identified only by ethnicity and age. What do you make of that? Curator: The lack of a proper name, it reinforces the exoticization of the “Orient” prevalent during the 19th century when Fortuny Marsal painted. We need to question this portrayal. Was this portrait created out of genuine respect, or does it perpetuate colonial gazes, reducing an individual to an anonymous "type"? Editor: Absolutely. Consider the head covering. Is it a cultural signifier, or a symbol deployed for artistic effect, feeding into pre-existing Western notions of "Arabness"? It certainly echoes the artist's own fascination with North Africa. The profile view adds another layer—he’s almost archetypal, impersonal. Curator: Precisely. We can unpack how the "Arab boy" becomes a stand-in for larger political narratives, operating as a symbol within an established colonial power dynamic. Is this “realism” simply aesthetic, or does it have real-world implications for representation? Editor: Fortuny clearly revels in capturing light on skin and fabric. Think of how this echoes religious paintings across time, where light signified holiness or some form of spiritual status. Perhaps here, light acts similarly to idealize or even sanctify a particular version of "Arab" identity? Curator: Or, perhaps it's another form of objectification—rendering flesh, textures as simply objects for aesthetic appreciation. It makes me uncomfortable when that exquisite detail comes at the cost of de-humanizing. Editor: It certainly asks more questions than it answers. The painting’s ambiguity sparks conversations we desperately need today regarding identity, representation, and the burden of history on single images. Curator: Indeed, engaging with Fortuny’s work forces us to think critically about our own expectations and biases when looking at depictions of cultures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.