print, engraving

#

portrait

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

cityscape

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

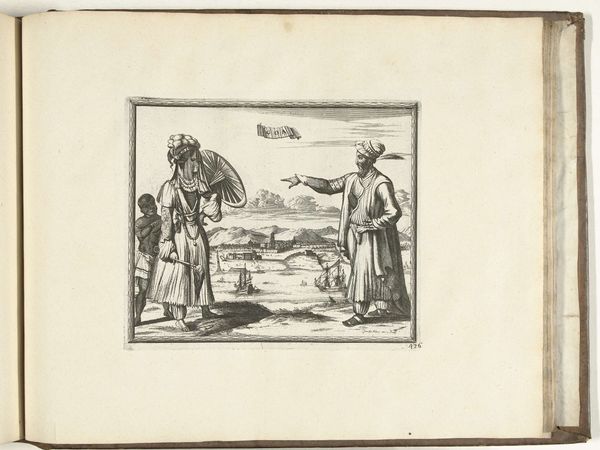

engraving

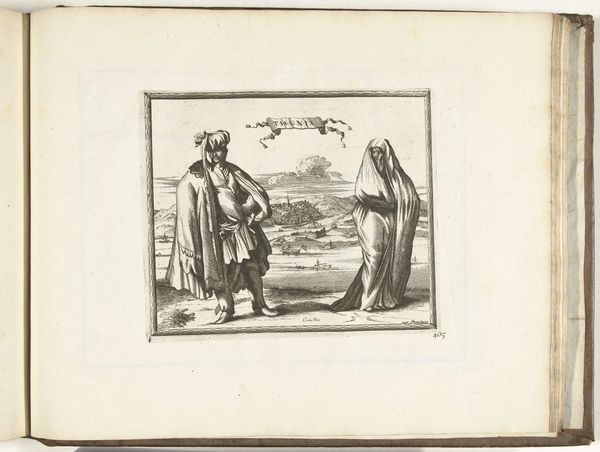

Dimensions: height 173 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, created by Carel Allard in 1726, is titled "Inwoners van Algiers, 1726," meaning "Inhabitants of Algiers." It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a stark, somewhat detached feel to it. The figures appear to be staged against a backdrop, rather than genuinely inhabiting the city. The crisp lines emphasize their clothing's materiality, like drapes hung up. Curator: Yes, the clothing is central to understanding this image. The way the textiles fall, the specific draping and forms, speaks to a carefully constructed visual identity. It presents an image of Algiers through costume, almost a theatrical display of North African identity as it would be viewed—and perhaps consumed—by a European audience. Editor: Interesting point. The meticulous rendering of the fabrics also leads me to think about the economic exchange that's occurring. Think about the material origins of these textiles. Where were they made? By whom? What were the working conditions involved in their creation? These aren't just clothes; they're indicators of trade routes and colonial power dynamics. Curator: Precisely. And it gets even more fascinating when you consider the pose of the figures. They are quite literally embodying ideas. The male figure, with his cloak, represents the power of the male inhabitants of Algiers at this time, as they may have been presented. While the female, equally adorned, showcases the visual symbols expected of women of standing. The clouds even resemble billowing sails. Editor: Those clouds almost resemble skulls, don't they? There's a haunting quality about them that underscores the transient nature of power and the human cost associated with this sort of cross-cultural exchange. Looking at the lines etched to render the ships, you also have to ask yourself about the role that manual labor played. It is one thing to see a city sketched from life and another thing to see a man's perspective represented on toned paper, for our viewing consumption. Curator: The scale of everything—from the labor that brought the paper into existence, to the fashion as commentary, and how everything seems to relate in context–lends an almost uncomfortable quality. Editor: It does provide us with much food for thought as we reconsider this piece through these very specific contexts. Curator: Absolutely. There’s so much layered here that simply focusing on style risks missing a vital social commentary, perhaps, which is timeless even to today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.