Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

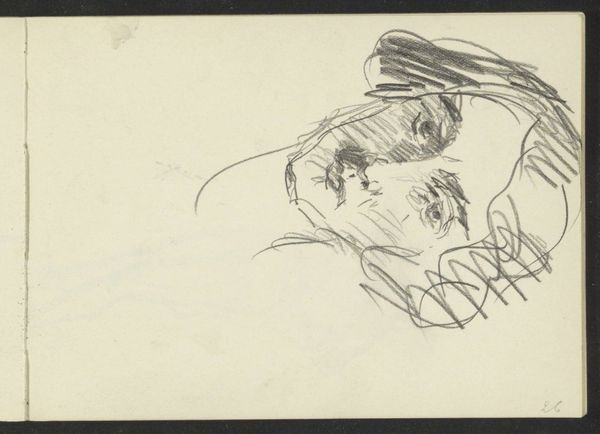

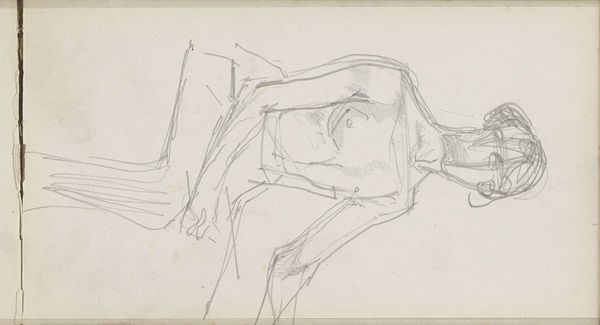

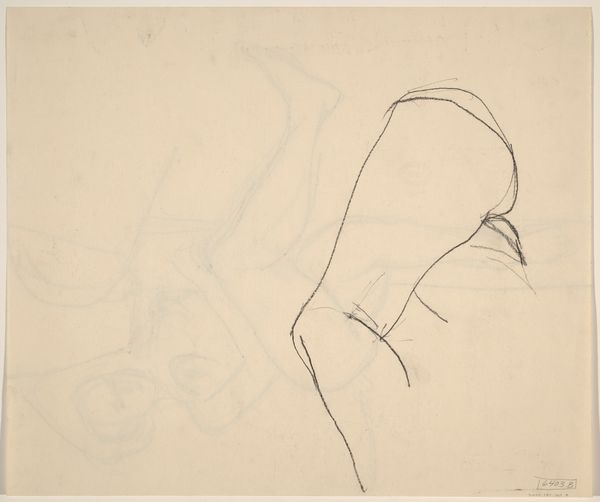

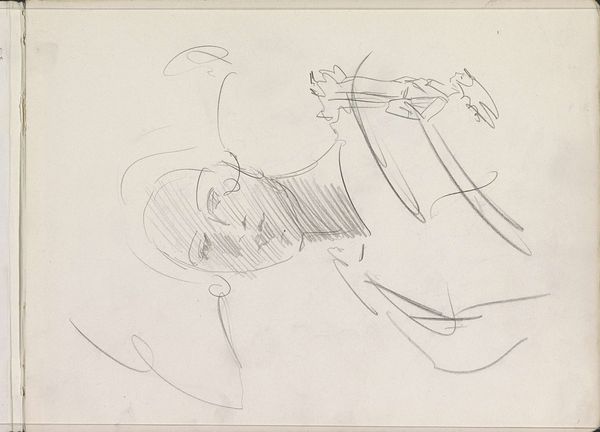

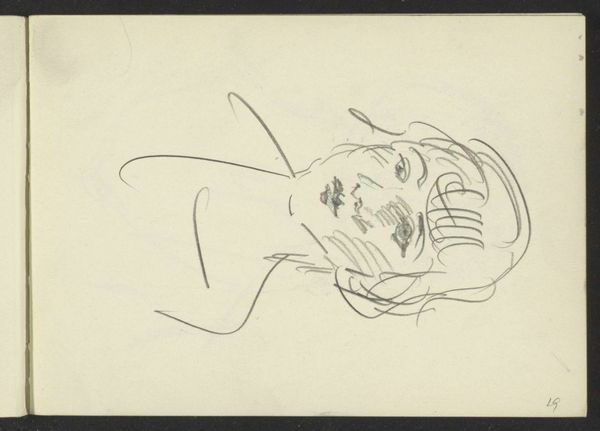

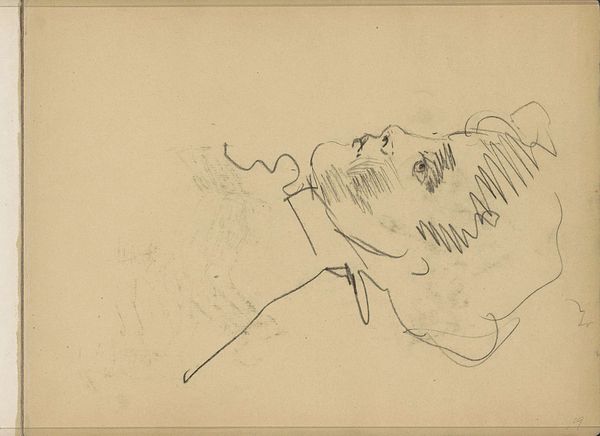

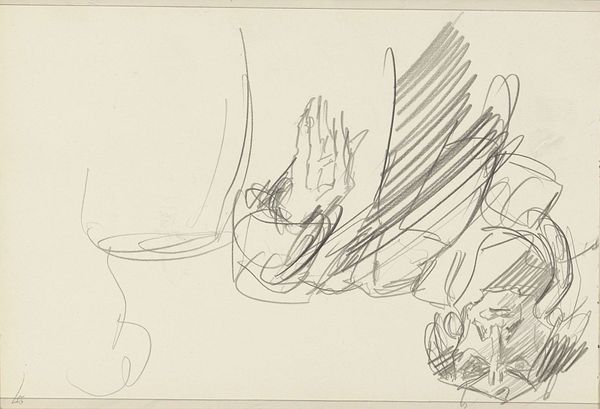

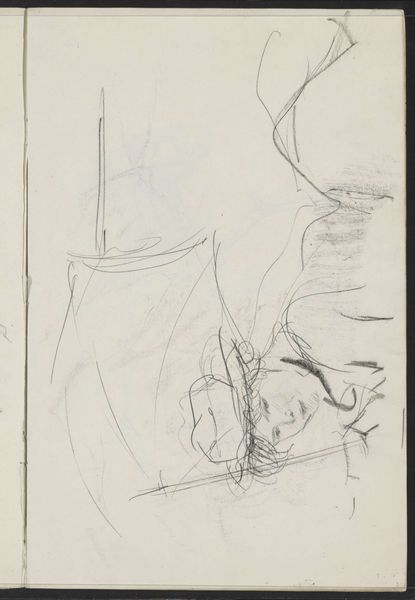

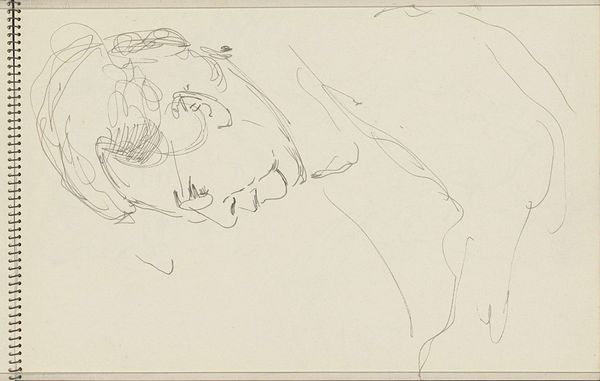

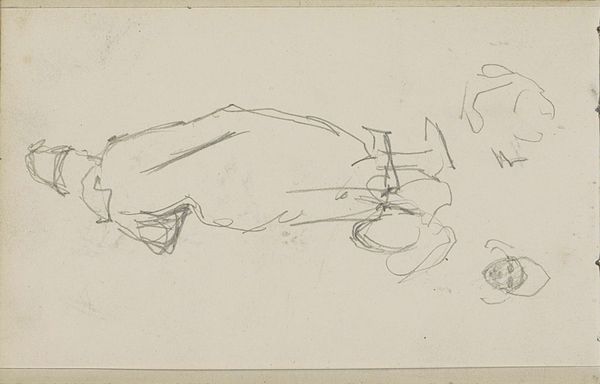

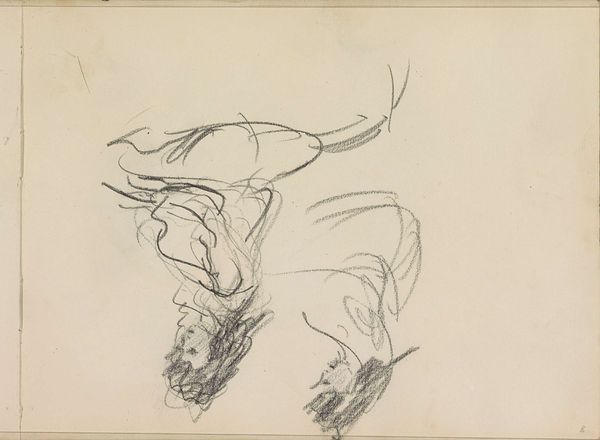

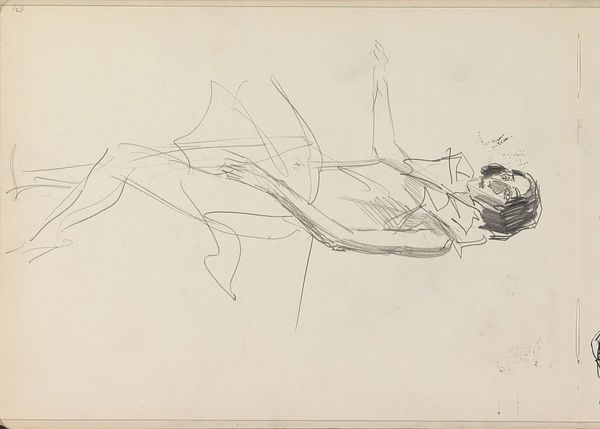

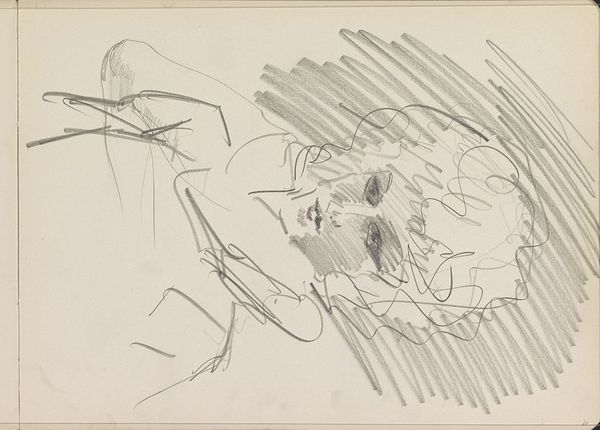

Editor: This drawing, "Twee figuurstudies" – Two Figure Studies – by Isaac Israels, was created sometime between 1875 and 1934, using pencil on paper. It's currently at the Rijksmuseum. The sketchy lines give it a sense of immediacy, like a quick impression. What do you see in this piece beyond that initial feeling? Curator: It's more than just a sketch; it’s a window into Israels' process, right? Think about the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Traditional academic art was being challenged. Artists were grappling with how to represent modern life and the rapid social changes happening around them. Israels, associated with Dutch Impressionism, was deeply invested in depicting contemporary subjects. Editor: So, this wasn’t about capturing some grand historical narrative? Curator: Exactly! It was about the everyday, the fleeting moment. Now, consider the figures themselves – who were they? Were they dancers, models, people Israels encountered in his social circles? The lack of precise detail, almost blurring of the lines, prompts us to question who has the privilege of representation and visibility and whose image gets obscured. The sketches remind me of Walter Benjamin's ideas on the aura of art, and how it shifts with mechanical reproduction, with photography, with mass media culture… how do you think that relates to the artwork? Editor: That’s interesting. So, instead of a polished portrait meant to immortalize someone important, this feels more like a study of anonymity and maybe even questions the value we place on specific people. The unfinished quality emphasizes that sense of impermanence, and suggests that maybe it’s the action of seeing, of recording, rather than what is depicted, that mattered to the artist. Curator: Precisely. And that connects to the broader artistic movements that were questioning those established hierarchies. What does this exploration of the "everyday" tell us about who was deemed worthy of representation in that time period, and who was ignored or marginalized? It can be about finding and amplifying stories we were taught not to value. Editor: This makes me consider not just who is represented but *how*. It really encourages you to ask "why," not just "what." Curator: Yes, looking closer reveals stories about both art history and ourselves. It asks questions about privilege and what and who gets remembered in history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.