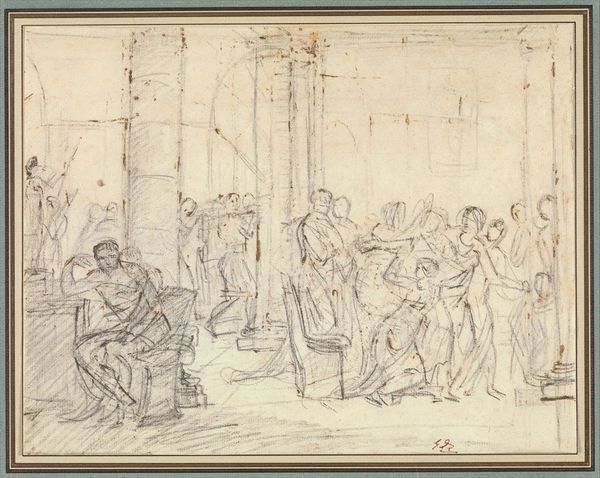

drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

sketch book

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 171 mm, width 291 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Pierre Louis Dubourcq’s "Studieblad met figuurtjes," created in 1831. It's a pencil drawing on paper, and the figures depicted seem to be performing various everyday tasks. What strikes me is how they all seem self-contained, separate from one another, despite sharing the same sheet. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Well, viewing this as a historical document, what I find intriguing is its glimpse into 19th-century social observation. It reminds us how art served as a form of visual ethnography. These aren't idealized figures; they're workers, seemingly ordinary people engaged in daily activities. But are they truly ordinary? How might Dubourcq's own social position have influenced how he chose to represent them, or even which figures he chose to include at all? Editor: That's interesting. So you're saying that it tells us about the artist and the people, and how the artist views the people in their society. How do you think a sketchbook like this might function within the broader art world? Curator: Sketches like this offered a vocabulary for larger compositions, reflecting the artist's worldview, consciously or not. The distribution of such sketches, be it in salons or published form, invariably shaped public perceptions and discourse around social classes. This seemingly innocuous study sheet played a role in defining social narratives. Consider, who was able to even access or consume artwork like this at the time? Editor: It’s amazing how much context can be layered into what seems like a simple study. Thanks for making me think more critically about how social context matters in works like this. Curator: Absolutely, seeing art as a reflection of and participant in social dynamics is essential. The art doesn’t happen in a vacuum, so neither should its appreciation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.