drawing, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

pencil work

Dimensions: 6 9/16 x 8 3/8 in. (16.67 x 21.27 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

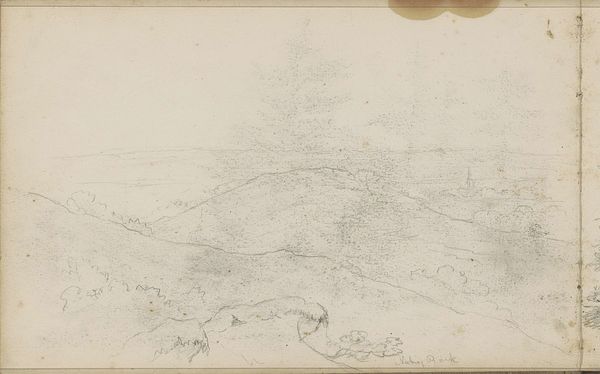

Curator: Before us we have "Rocky Promontory", a pencil drawing from 1834 by Theodore Rousseau, currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. Editor: The landscape, rendered with such delicate strokes, evokes a sense of tranquility, almost fragile. There is a sense of space and isolation in this rather simple composition. Curator: Indeed. Rousseau, as part of the Barbizon school, sought to move away from the idealized landscapes of the academy, choosing instead to depict the French countryside as he saw it, with its imperfections and its untamed beauty. The simplicity you noted can be viewed as a subtle political statement against established norms. Editor: Absolutely. I’m immediately drawn to the steeple barely suggested on the horizon. How would that signify for the local population viewing the landscape, being literally grounded in the landscape as much as aspiring beyond it? Curator: It’s tempting to interpret the church steeple as a symbol of tradition, even dominance, in a society undergoing rapid change during the Romantic era. One could even view the subdued rendering of the land as representative of suppressed rural populations. How were they connected to the land and losing their grounds due to capitalism? Editor: Precisely! While it would be reductionist to limit ourselves, that cultural and artistic memory of landscapes of hope or promise and cultural connection always makes me wonder if these simpler compositions represent something more than just a scenery study. It’s interesting to note how he doesn’t include humans in this drawing. Curator: Good point. That absence invites viewers to reflect on our own relationship with the natural world. Rousseau is positioning the scene to underscore our relative place in the natural environment; we are implied and small against an ever indifferent Mother Earth. Editor: Right. The piece holds onto the essence of how environments evolve through imagery—an icon, really—becoming an extension of memory, not simply a thing apart from us. Curator: Indeed. And seeing this image, perhaps it causes some of us to consider the relationship between rural life and the state. Editor: A simple pencil drawing; so much depth! Curator: Exactly, there is no final, complete viewing, there is simply conversation with art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.